-AG hails launch of Guyana’s first Mental Health Court

-Chancellor highlights transformative power of therapeutic jurisprudence

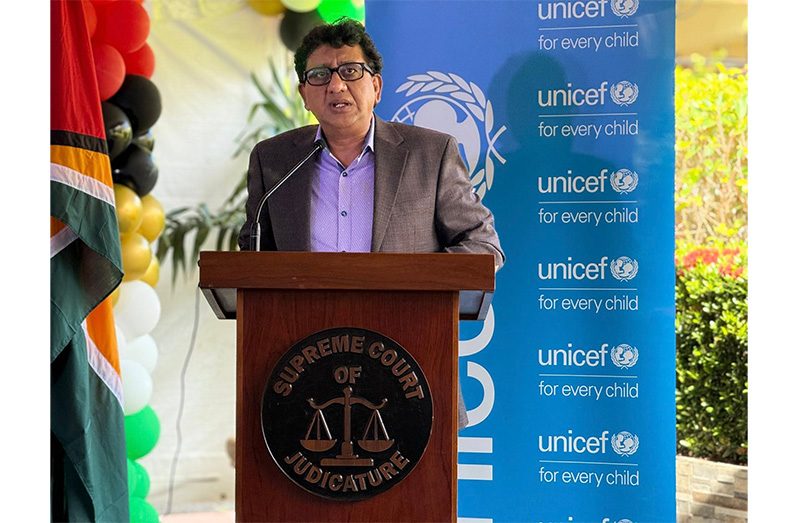

DESCRIBING the moment as “simple but momentous,” Attorney-General and Minister of Legal Affairs, Anil Nandlall, SC, on Thursday hailed the official launch of Guyana’s first Mental Health Court as a historic milestone in the country’s justice and human rights landscape.

This specialised court is to be established at the Georgetown Magistrates’ Courts.

The Mental Health Court, launched at the Supreme Court of Judicature in Georgetown, is the first of its kind in Guyana and is designed to ensure fairer treatment for defendants whose mental illness may have played a role in the commission of criminal offences.

“This is historic and groundbreaking as this is the first court of its type that is being established in Guyana,” Nandlall said in his address. “The opening of the Mental Health Court is an outstanding testament to the evolution and maturity of our society to holistically address the issue of mental health in Guyana.”

The court’s establishment comes on the heels of the newly launched Children’s Court at the Charity Magistrate’s Court—an initiative tied to the full implementation of the Juvenile Justice Act.

Together, these developments reflect the government’s commitment to expanding specialised courts to meet the unique needs of vulnerable populations.

According to Nandlall, the Mental Health Court aligns squarely with the government’s broader policy agenda to improve the lives of persons living with mental illness, reduce the prison population, and cut down on recidivism.

“Historically, persons with mental illnesses faced discrimination, stigmatisation and were relegated to living on the fringes of society,” Nandlall stated. “They are referred to as mad, crazy, or insane, with their condition being grossly misunderstood.”

He pointed to the significance of the Mental Health Protection and Promotion Act 2022, noting that Section 21 of the legislation guarantees equal access to justice for persons with mental health conditions and their right to participate fully in legal proceedings.

The AG noted that Guyana’s Mental Health Protection and Promotion Act stands as one of the most modern pieces of mental health legislation in the region—perhaps even globally.

He pointed out that with its enactment, Guyana has fulfilled its obligations under numerous international human rights conventions, including the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Prior to the enactment of the 2022 law, he explained that Guyana relied on the outdated Mental Health Ordinance of 1930, which was modeled on the United Kingdom’s 1890 Lunacy Act.

That colonial-era framework, Nandlall emphasised, viewed mentally ill persons as deserving of institutionalisation and exclusion from society.

He also signaled the possible need for additional legislation or procedural rules to guide the operations of the Mental Health Court moving forward.

“This court establishes the fact that we have matured significantly as a society,” Nandlall said. “There is still much to be done in upholding human rights, and mental health care is of utmost importance if our society is to develop in the direction we hope.”

He referenced the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) definition of mental health as a “state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realise their abilities, learn and work well, and contribute to their community.”

He emphasised, drawing on the WHO definition, that mental health is a basic human right and is crucial to personal, community and socio-economic development.

The Senior Counsel explained that the Mental Health Court is further strengthened by the Suicide Prevention Act of 2022, which decriminalised suicide in Guyana, as well as by ongoing mental health training initiatives under the Support for Criminal Justice Programme (SCJP), supported by funding from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).

As part of that programme, 60 prisoners were recently trained in mental health by the University of Guyana, in partnership with the Guyana Prison Service and the University of Leicester, as part of efforts to address the gaps in mental health care within the country’s prison system.

In closing, Nandlall reaffirmed the government’s commitment to enhancing the health and well-being of all citizens, noting that it is national policy to ensure access to quality healthcare for everyone, regardless of where they live. He referenced the ongoing construction of several modern hospitals across the country as part of this effort.

“The Government of Guyana remains willing and ready to work with the judiciary to provide all the requisite resources to ensure that this court is successful, and to ensure that this initiative is replicated across the 10 administrative regions,” he added.

THERAPEUTIC JURISPRUDENCE

Meanwhile, Chancellor of the Judiciary (ag) Justice Yonette Cummings-Edwards, underscored the transformative role of the Mental Health Court, highlighting that it is not merely about trying cases and issuing punishments, but about offering a more compassionate, holistic, and rehabilitative approach to justice for individuals living with mental health challenges.

“The court is not here only to try the case, lock you up—put you into the prisons and throw away the keys. It is a more holistic, compassionate, and healing procedure which we undertake in our various treatment courts,” she stated.

“We are witnessing therapeutic jurisprudence, which is an interdisciplinary approach to solving legal issues and which impacts positively on defendants/participants.”

Therapeutic jurisprudence (TJ) is a perspective that examines how legal rules, procedures, and practices affect the psychological well-being of individuals involved in the legal system.

It is a multidisciplinary approach that draws on behavioral sciences to understand the impact of law on individuals, aiming to reduce negative psychological consequences and promote positive outcomes.

The Mental Health Court is the judiciary’s second specialised treatment court, following the establishment of the Drug Treatment Court in 2019.

The Chancellor noted that judicial officers have received training in mental health and substance abuse, highlighting that in establishing these specialised courts, the judiciary has been guided by best practices adopted from the United States of America (USA) and Bermuda.

She pointed out that history is being made through the collaborative efforts of key stakeholders, including the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Human Services and Social Security.

Emphasising the justice system’s growing focus on rehabilitation and support, Justice Cummings-Edwards assured that individuals who come into contact with the courts will receive the necessary assistance to improve their well-being and ultimately lead better, more stable lives.

“We will ensure that persons who pass through the justice system will be given the required help,” she said, while also noting that participation in the court’s services is entirely voluntary.

While the Mental Health Court was being launched in Georgetown, a simultaneous launch took place at the Bartica Magistrate’s Court. To increase public understanding of the initiative, the Chancellor announced that the judiciary will soon roll out a public awareness campaign.

ON THE WAY TO ACHIEVING SDGs

Gabriel Vockel, Deputy Representative of UNICEF Guyana and Suriname, stated that the organisation provided both technical support and funding for the establishment of the Mental Health Court.

He noted UNICEF’s commitment to advancing a justice system that is inclusive, rehabilitative, and sensitive to the needs of children.

“This Mental Health Court represents an important step forward in ensuring access to justice for all, and particularly for persons with mental health illnesses and intellectual disabilities, which is in line with Guyana’s Mental Health Protection and Promotion Act,” said Vockel, a German-trained judge.

Vockel highlighted that the Act guarantees persons with mental illnesses equal access to justice and the right to participate fully in the administration of justice—an ideal that lies at the core of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

“Today’s launch is a clear signal that Guyana is committed to delivering on these goals in a meaningful and rights-based manner. This court is significant because it will recognise the complex intersection of mental illness, intellectual abilities, and criminal behaviour.”

Vockel added: “And by adopting a therapeutic jurisprudence model, it will transform the legal system into a real tool not just for correction, but for healing and rehabilitation…. It will also emphasise treatment over punishment… The law can be a tool of compassion.”

Also present at the launch were Chief Justice (ag) Roxane George, SC, along with several other judicial officers.