By Abigail Persaud Cheddie

WHEN the kitchen clock chimed five on my birthday morning, I rolled the bed covers into a ball and stood up to see if I had grown. Then holding my breath, I tiptoed in the dark to the bedroom window, eased the bolt up, minding its squeaking so as not to wake Ivy, gently pushed open half of the wooden window and looked for the outline of Suzie’s very square house. I wondered when she’d rise and get dressed for my party.

Except for the cock-a-doodle-doos and the silhouette of two cane cutters hurrying along carrying lunch pails, the world lay still. So I pulled the window in, climbed back in bed and waited for my birthday. But I fell asleep again and awoke to the sizzling of sausages and eggs and Pap flinging open windows and singing, “Woo! Ixie Pixie! Ivy Jivey! Birdday time! Wake up! Ooodle-doodleey-ooo.”

He went out again and returned with Mam, the two of them bearing a shiny package the size of three yam crates. I crawled over the bed, poking Ivy in the ribs as I went.

“Iveey wake up, look.”

Ivy wobbled over. “Is what? Is what?” she croaked, tugging at the bow and peeling off the wrapping.

It was a house! A wooden house that Pap had built! The roof could lift off and the door and windows were large enough to stick our hands through and arrange the accessories.

“Happidy bwirday,” Pap said and squished us to his tummy.

Mam set her arms akimbo and smiled.

“You can paint it any colours you like,” said Pap.

“Looka dis,” said Ivy, lifting and replacing the whole floor.

“Why it coming out like so?” I asked, peering at the second flooring underneath the detachable floor.

“So it could work like a trapdoor. Like in mystery stories, you know? You could call it a trapfloor,” Pap explained. He seemed pleased with himself.

But I didn’t know much about trapdoors or floors yet, about how they could lock things away, hide them, create the illusion that what you saw was the whole house.

“Alright,” said Mam, drawing us away from the house, “come help me get out your breakfast. Y’all turn seven now, is time enough. I been making my own since I was four.”

She handed Ivy a butter knife and bread and let me brew the tea while she finished decorating the cake, first drawing a seven, then beneath it, writing Ixora and Ivy.

“How come you always write Ixie first?” Ivy said, breaking off and eating an icing leaf.

Mam smacked her hand. “Jus’ ’cus she born first. Stop dat.”

“Naa-naa-na-boo-boo, Iii borrn firrst,” I said.

“So?” Ivy said. She broke another leaf and crammed it in her mouth.

Mam smacked her hand again.

“So!” I said and dropped a wet teabag on her head.

“So?” Ivy said, and wearing the teabag like a crown, she put on a show with the green icing stuck to her teeth.

“Yuck. Close it!”

But she opened her mouth wider like Pollard. Pollard was Uncle Warbin’s sakiwinki monkey. We used to feed him sour fig bananas and he used to jeer at us and sit on our shoulders while we strolled around the village so that children could come up and shake his hand, which he’d oblige if he was in the mood.

But that was before he was stolen.

“Uck,” I said. “You look like Pollard eating green peas.”

“And you look like –”

“Shush,” Mam snapped. “Since you old enough to argue, you old enough to bathe and dress yuhself. Gwan.”

So we scrubbed and rinsed and shoved each other into the pink polka dot dresses and presented ourselves to Mam.

“Not bad,” she said, sounding pleased for a change. Then she grabbed the jumbo toothed comb and started yanking the knots out of Ivy’s hair and while they tussled over the hair and Ivy alternated between “ouch” and “oww” until her hair was up in a puffy ballerina bun, I and my pink polka dots and frills sidled to the veranda.

It was drizzling.

What a harrowing thought, I thought – only I didn’t actually use the word harrowing in my mind – I didn’t know the word harrowing then, but I did conjure up the feeling of what harrowing meant – what a harrowing thought, to think that it might rain and everyone had to cram in the old kitchen and living room where Mam and Ganee Gwenny needed to get about to serve lunch. They might trip over us, and then the chowmein and cook-up rice would pitch about in the air and fly into our hair and board games.

Harrowing.

But no matter. Suzie and I could fit behind Pappo Harro’s rocking chair and play the chequers there.

“It’s drizzling Mam,” I said, but only because I thought I should be magnanimous and warn everyone. Not because the rain had anything to do with me. I adjusted my dress frills.

“The rain might go ’way man. Come here.”

She started combing knots out of my hair.

“Ouuch.”

“Girl, stop wriggling.”

Pap appeared with an arrangement of ixora flowers and ivy leaves set in a crystal vase.

“And now, presenting – Igzzora,” he gestured towards the red flowers, “annd Ivee.”

He flourished his hands at the green cascading leaves, then paused.

“Get it?” he said. “Ixxzoh –”

“Pap, we get it, we get it, we know,” Ivy said before Pap could prolong his ritual theatrics.

I laughed and Pap rolled his eyes, shook his head at his philistine offspring and sailed off to display the vase near to the cake on the veranda.

On his way back through the living room he carefully transported our ixora garlands that I’d rested on the birthday table. Mam loosened her grip on my hair so we could put them on.

Ivy and I looked in the floor length mirror. We were just like Sally Hallie at high tea. We were two, and darker with fluffy hair, but definitely just like Sally Hallie.

I swirled the polka dots around me and admired my flower necklace.

Suddenly it struck me, Suzie would need one too, a flower necklace. I hadn’t thought to make her one. My heart started up bouncing on the bridge of my chest. I didn’t want Suzie to feel left out.

I contemplated dashing outside and gathering more flowers. But I couldn’t. People were almost here. Suzie was almost here. When could I … tomorrow, tomorrow I’d make one for her, for sure. I’d tell her. I’d tell her, first thing, as soon as she came through the gate.

Mam took hold of my hair again while Ivy went to see who was shaking the gate.

“Come in,” she said to someone out there, “Just push dat gate. Pussh. Oh, thanks. Look Mam, Junior bring we a gift. We could open it?”

“If you want.”

“Lemme see,” I said and wriggled from Mam’s grip.

It was a five by four inch superbly thin colouring book with a packet of four crayons.

“Ooo, thanks Junior,” I said.

Someone else rattled the rickety gate and Ivy started shouting again, “Oi, No-Jo push. No, push. Not pull! Noo man pusssh it I said!”

She and Junior went down to help.

“What a dunce, boy,” I said, “he dunno what’s push and what’s pull?”

“Don’t lemme hear you callin’ nobody dunce again,” Mam said and shoved a hair pin into my precarious ballerina bun.

I was losing patience watching Mam in the mirror as she tussled with the gravity-defying bun.

Junior had come. No Jo was out there. Others were coming in. Suzie must be out there too. She must have brought me a new skipping rope under the shiny wrapping. The rope I had was fraying and one of the handles was broken and she knew that. Or maybe it was just socks. Most children’s mothers sent socks. But that didn’t matter. Socks were fine and functional, as Mam would say.

Socks are fine and functional.

“Hurry Mam,” I pleaded, as she added hairdressing cream until my head shone from forehead to crown.

“Mam, hurry.”

By lunch hour almost everyone had come. Even Uncle Raffie arrived on time with Lennard and Annie-Lou.

Everyone scarfed down their lunch and hustled to the games. Junior and No-Jo managed the cricket. They had Small Spokes fielding the ball, running up and down like a puppy playing fetch.

And Ivy and Anahita, Kathi, Lotte, Imani, Adalia, Basmati and Jia, whichever they were – it didn’t always matter as they looked and ran about the same anyway – they carried on with their random games, screeching like parrots.

But that was no business of mine. I stayed on the veranda while the parrots screeched below and I fixed my eyes up at Suzie’s stairs.

She was being maddeningly slow today. Maddeningly, such a nice word, I thought. Maad-en-ing-ly. Maad-in-eng lee. I’d heard a teacher on the top floor at school saying that word.

Lunch hour flowed by and Ganee Gwenny and Pappo Harro glided about with silver trays serving the jello and the quarter pint ice cream in rainbow bowls.

“Don’t share away Suzie ice cream,” I said, looking across the street. “Keep a yellow one for her, or peach.”

I went and leaned by our open gate. The broiling sun burned down on my ballerina bun and through my pink polka dots. But the drizzle was starting up again.

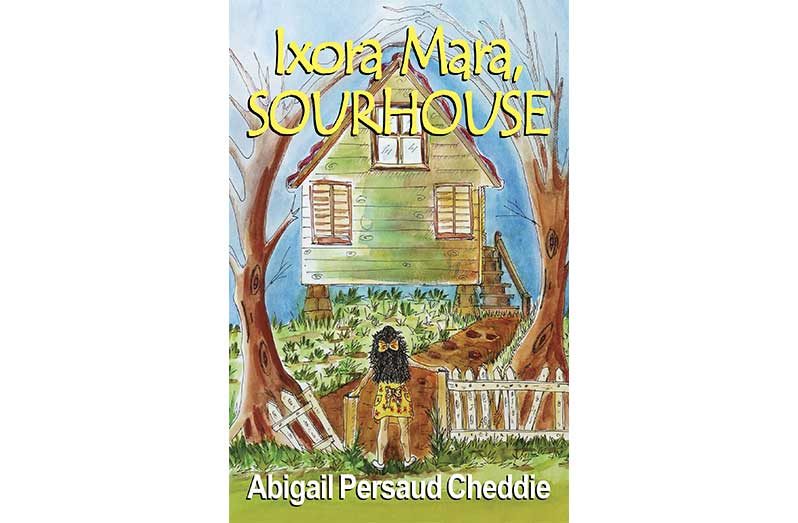

About the Author

Abigail Persaud Cheddie is a Guyanese author whose debut novel, Ixora Mara, Sourhouse, won the Special Judges Prize for Young Adult Fiction at the 2024 Guyana Prize for Literature. She also served as an English literature lecturer at the University of Guyana for 17 years. According to Cheddie, the novel had been 20 years in the making, having first come up with its inspiration when she was 16.

.jpg)