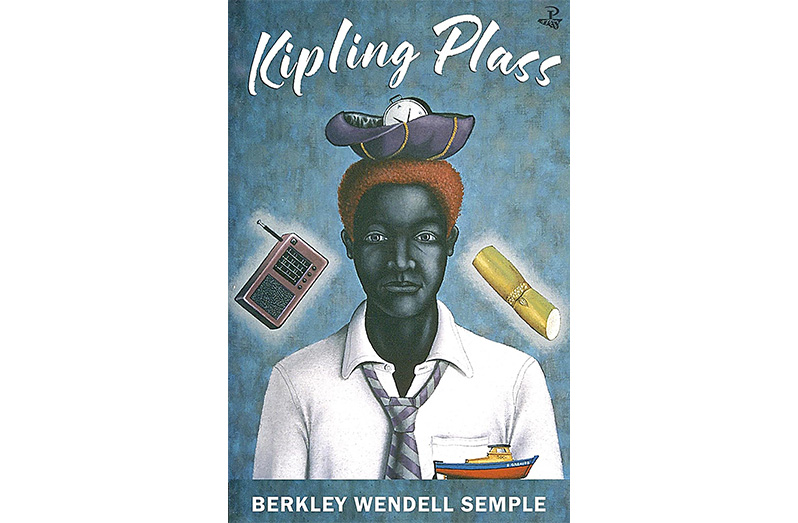

EXCERPT CHAPTER FROM ‘KIPLING PLASS’ BY BERKLEY SEMPLE

I GO with Pandit Karl Singh to Dundee to meet a man about some cassava sticks. He says I must come with him to fetch them back to the mandir. But when we get on the road and I stand to flag down a car, Pandit say no, we walking. Is a good long way to Dundee, and the sun blazing hot; already I sweating like pig and smelling like one, too. No breeze blowing, and the air dry and hard to breathe. All the trees still, and a thick trembling pane of heat shimmer in the distance up the road. Main Road quiet; almost nobody out. Is nearly twelve noon. I take off my jersey and wipe perspiration from my armpit and tuck it in my pants waist and let it hang down low, like badman in a filmshow.

Pundit Singh wearing his white kurta and his cricket cap, but his feet bare on the burning road, his foot them clapping loud on the asphalt.

He is from Tunapuna in Trinidad, but you can’t tell from hearing he talk. He talk like Guyanese, not in the sing-songy style. Is because he come to Guyana a long-long time ago. Then he go to India and study this pandit business and come back here. He live bachelor style in the house behind the mandir. He tell me and Carl that long time ago he had a wife but, “I had to put she aside for certain reasons I cannot mention.” Pundit Singh sometimes talk Hindi or Urdu, which he say is the Coolie language of the real India Indians, in places like Bombay and Delhi. He read the books of the man Tagore and Harivansh Rai Bachchan in Hindi. He try to teach me a few of the words, but I don’t take on the thing too hard, so he just give me R.K. Narayan’s The Vendor of Sweets, written in English.

Pandit Singh is the opposite of Pandit P. He always calm and plain and direct. The only thing I don’t care for is that he always telling truth, even if it hurts. He don’t spare you. He get people vex when he start with the truth-telling business, and looking you straight in the face with his bright-bright eyes, pointing out your dutty ways. He make people uncomfortable.

In Goodfaith, we stop and go in a small shop and he buy two cream soda and sit at a small table. No one in the place except a man called Everytime I Let You Have Your Way Marie. The man nickname is a whole sentence and I never understand how he come by it; what I know for sure is that nobody call he anything else. He sitting at a table by heself, moving chess pieces across the board and studying the moves.

Pandit Singh say, “Good afternoon, Every Time I Let You Have Your Way Marie, things alright?”

“Things is so and things is such,” the man say, “but we must make do, must we not?”

“Yes,” say the pundit, “we must.”

I drinking my drink and Pundit Singh looking at me in a keen way, like he trying to read my mind with he bright-bright eyes and tar-black pupils. Something not right about the way he looking at me.

“Man is violent and cruel,” he say, “but he don’t have to be.”

Is not something I disagree with, but I wonder why he bringing up this idea right now?

“Yeah, man cruel bad,” I say.

“I was on my back veranda the other night,” he say, “looking out into the nighttime. The night was dark, but I have good eyes. I always have good eyes, Kippy, so good I can see through the most tenebrous night. You know the word?”

I nodded, yes.

“And what I see in the dark, Kip, I go tell. I see a dark-skin boy with red hair moving between the trees. Is not jumbie or bacoo or any other evil spirit. I look close and see is a boy with a bottle of kerosene in he hand. I see he jump the fence and go into Dado yard. I watch he good and proper, and shake my head cause I think he going to thief mango or even a fowlcock. But not long after, the boy jump back over the fence and leave a big fire behind he. The boy wicked, Kip. What can be done with this cruel boy who burning up turkey and chicken and guinea fowl? Is a vicious thing that and I want to understand this boy. I must know if he heart black as he face. I want to know, if the act of fowl murder is an inkling of what this nasty dutty boy will do in the future? Look me in the eye and tell me.”

All this time Pandit Singh talking, I thinking of them fowl in the coop, flapping around with fire in their feather, with flame burning them and nowhere to run, no trench to jump into and no sand to bury their burning heads. I think of the pain they can’t explain with their fowl-talk and their cock-a-doodle-doo. I imagine them fluttering in panic in the coop, and the flames burning them all. Then I imagine being trapped in a burning house. I run to get out, but fire in the way around the door, and the heat hotter than the sun, and the smoke choking me; it snakes in through my nose when I breathe; it cork up my nose-holes and go in my lung and I can’t breathe. I only coughing and now fire is inside me, burning a way out, and now I am the fire, and I blaze like a burning sun

I start to cry right there.

“Yes,” he say, “you crying. This mean something. You recognise you do something wrong. Is good to see. Your heart can’t be same way as the colour of your face.”

I look at him, not sure what he mean, trying to read meaning in his eyes.

“You want to understand what I mean?”

“Yes,” I say.

“You want to understand the blackness of the blackness? You want me to explain how darkness different from blackness? You want to know my meaning?”

I nod my head like dasheen leaf in the rain.

“Kip, you so black I can barely see you in the dark, and with your red whiteman hair and cat-eye, everybody can tell you is not regular, and them know you is a incest child and devil boy. Truth is, you is like a clown boy in a flimshow. I ain’t making insult or tantalizing you. I just saying we must live with what we get. We must make do, you and me, with who we are. Everybody have their own cross to bear and some more heavy than others but is either you bear up or buckle and fall. Every man have to bear he chafe, and is fall apart or stay whole. So, don’t cry to me plenty eye-water. What we need is a scheme to get we out this place; we need to make a way from no way. We not born with no silver spoon in we mouth; we family is not in no position to help we when we braced hard against a wall. What we have to sell? Nothing! We not worth much, Kippy; we not precious like gold or shiny and bright like diamond. We poor and dark and nothing can erase this. We can’t start over in the womb of a rich woman and come out bawling with pride and vanity, knowing the privilege we have since we born. We come from a poor womb into the world, silent and shame-faced and hungry. We always hungry, not for food, boy, no, we starving for something we can’t name and don’t know. We lack something deep inside. And how to proceed is the question; where to put we feet when we walk is the consideration; what word to say and act to do is the challenge. We not confident. I think poor people not confident; they always doubt what they know for sure, doubting what is true. In the face of rich and powerful people we lose weself and become silent and useless. Our feet are moved by them here and there like pawn in a chess game. We live a vexed life, so we prove we power by burning chicken, drowning dogs, beating children and abusing women. Is no justice in that, is just cruelty. What you did is not justice, Kip. Is a dark thing, darker than your face; it cannot be the colour of your heart. Is nothing wrong with blackness. I just as black as you, and that is why we must be careful. You see me, Kip?”

“I see you, Pandit,” I say.

“Now drink up and come. We get things to do today.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Berkley Wendell Semple was born in Guyana. He has published four collections of poetry, Lamplight Teller, awarded a 2004 Guyana Prize for Poetry, The Solo Flyer, The Central Station, and Flight and Other Poems, awarded the 2023 Guyana Prize for Literature, and has edited a book of student poems. His poetry and fiction have appeared in Callaloo, The Hampden-Sydney Review, The Caribbean Writer, for which he was awarded a Daily News Prize for poetry, and many other publications. His debut novel, Kipling Plass was named best first novel at the 2024 Guyana Prize. He is a veteran of the US armed forces and a graduate of the Naval School of Health Sciences. He holds an MA and MLS degrees from Queens College of the City University of New York (CUNY) and an MPhil from Long Island University (LIU) where he is a current Ph.D. candidate. From 2010 to 2022 he wrote audiobook reviews for Sound Commentary Journal. He is on the Editorial Board of The Caribbean Writer, and an editor and book reviewer for Caribbean Voice. Berkley Wendell Semple is a librarian and currently works for the Queens Public Library system in New York City.

.jpg)