THE overall attitude of post-emancipation can be translated into several expressions. Among the indentured peoples that the English Plantocracy embraced were the Portuguese, who had failed as plantation field workers, and whom the Plantocracy intended to use to deter Africans from returning to the plantations, whose fortunes were slowly declining due to the introduction of the industrial era, among other factors.

The British Governors were eager to support the plantation owners in the process of denying former slaves, who were still without land, the opportunity to acquire it. The purchased lands were subject to heavy taxes, and the Colonial state declined to undertake the agreed-upon tasks that accompanied the taxes, which became the responsibility of the state, including drainage works, etc. Taxation was also heavily imposed on the imports that the common man required, including wheat flour, cornmeal, codfish, soap, and candles. This kind of discriminatory taxation bore very heavily on the Creole working people.

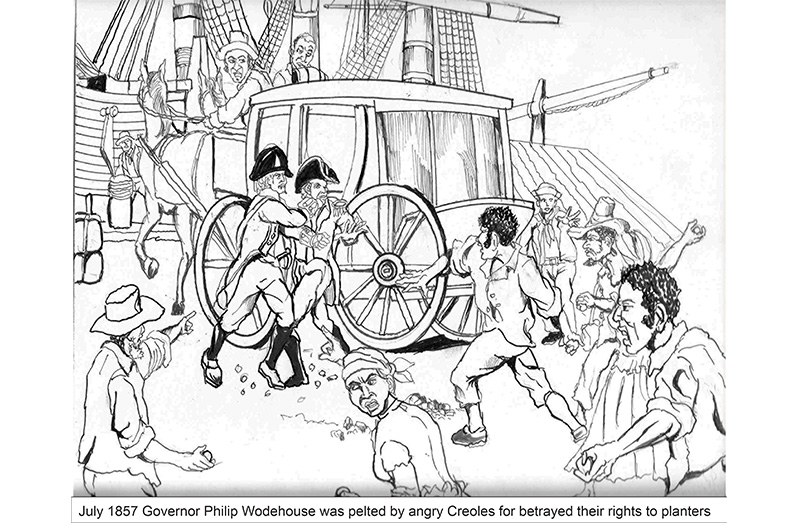

Because of the great hardships generated by this impost, it aroused considerable hostility not only towards the Portuguese but also towards its chief architect, Governor Philip Wodehouse, against whom the Creoles vented their anger by stoning him on his way to the Stabroek Wharf in July 1857. This punitive tax was mercifully repealed in 1858 after much orchestrated protest from the missionaries and other local pressure groups, as well as the Anti-Slavery groups in Britain.

The era of prejudice directed at the Creole was founded on the secret intent to have control of the Creole population at all levels, through diminishing their livelihoods and ambitions.

“The Pajama managers of the new mining industry” were replaced by the risk-taking “Creole Pork-knockers” who would themselves witness the same transition of mining labour branching out on its own initiative, to cease exploitation. What is extremely important, however, is that while Africans recognised the planters’ plight, they did not concede the planters’ assumed rights to attack their living standards and the freedom for which they had fought and won. What the villagers were adamant about defending was the value of their lives and the worthiness of their efforts to sustain their families.

In 1900, the lot of urban and rural workers was inevitable: the cost of living was high, while wages were low and stationary. The working day was long and there was a high level of unemployment. There were no trade unions, no political representation. The Government was indifferent. It was against this attitude that the trade union movement was born. One must not forget that emancipation evolved in the air of several hundred years of twisted racist belief systems that were used to justify planter rights as superior. Such dogmas had religious concoctions that justified both slavery and colonisation. Racism played a significant role at all times, including the Independence era.

It is essential to note, however, that only a small minority of Creoles achieved significant upward mobility – notably doctors and lawyers, those who became civil servants, teachers, priests, policemen, and clerks. Civil servants entered the middle class, alongside skilled artisans and craftsmen, and seamstresses. However, the vast majority of Creoles remained working class, struggling to make ends meet. Many did not survive the hardships of life in the racist colonial society.

(See Themes in African-Guyanese History by Brian L. Moore).

.jpg)