I WASN’T brought up in the age of TV. Though my generation knew that television existed, we were loyal to the cinemas and the many bookstands and bookstores, so, we didn’t complain.

I was about 13-plus when I was given the first book for my personal library. It was a book without pictures. My friends and I preferred books with sketches or with coloured artwork such as Treasure Island, which I learned two generations later that the artwork was done by the American artist N.C. Wyeth.

Now, to that first book that I was given, ‘Aesop’s Tales’: I loved the stories, especially because I was told about him, that he was also called Esop, being the same as Ethiopian in his era. The tales of Esop were grounded in philosophical awareness that would enable us to adjust to the true nature of humanity close and afar. The next book was given to me by a relative who insisted that this book would teach me a lot the world of my early 20s was losing. That was a big, gloomy prediction then, but today, he is more on the ball. That book, “Man The Bridge Between Two Worlds,’’ if I had not read Esop or Aesop, understanding the latter content would not have been that accessible.

What we’re losing is the symbolic language of folk story time and, worse, the awareness of personal decisions based on prior knowledge and the capacity to analyse good against wrong, further. A religious example illustrates that morality was a matter of obedience rather than a moral individual choice. It never occurred to Abraham that the sacrifice of his own son, demanded by Yahweh, could be immoral. The remarkable fact was that the Bible had nothing but praise for Abraham’s readiness to bring a human sacrifice. Was this common practice in a different age? ‘Paraphrased without disrupting content, ‘Man the Bridge…’ Why is there a need to question the dissemination of core awareness with respect to balancing religious or spiritual beliefs within the context of profound moral ideals? The when and why “There is a time for everything.” We are a country with too many violent, fatal human incidents impacting young citizens without a murmur that recognises, defines, or can inspire.

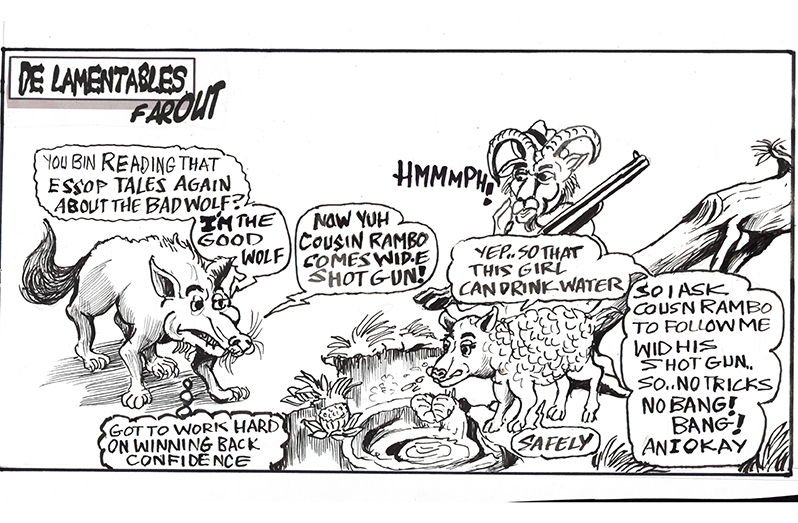

In Esop’s Fables, the narratives are more direct. I bought another issue of this book some years ago for my last child. I told her who Esop was because this edition was completely Europeanised. Page 5 carried the story of the Wolf And The Lamb. The hungry wolf came upon the lamb by the stream and began all sorts of accusations towards the lamb, to which the lamb responded respectfully, proving the wolf wrong, but when the lamb least expected, the wolf seized the lamb, slew it and devoured it. The moral of that story is that the wicked will always find a twisted reason to commit wrongdoing.

What we can extract from the process of experience is that childhood readings, those of us who have benefited from it, have endeavoured us to understand better the actions before us and, at times, the rehearsed deceptions proposed, which can help to cease the mental tensions of promises by persons trusted.

Our children must never be the ill-fated lamb that is confused by the empty accusations of the wolf, who, in the end, devours the naïve lamb. Get them reading, do what I did in my early working years: visit the second-hand book stands and purchase relevant books. They wouldn’t learn everything on a phone. Get them accustomed to reading.