FROM Berbice to the global stage, poultry nutritionist, Dr Colwayne Morris, is transforming how farmers view poultry nutrition—and how young people view agriculture.

As Guyana closes the curtains on Agriculture Month, Dr Morris is proving that what’s good for the chicken is good for the nation. The Berbice-born poultry nutritionist, now based abroad, has built his career around understanding how feed quality shapes not only animal health but also the food security and livelihoods of those who depend on poultry production. With a passion that stretches from the lab to the classroom, Dr Morris is helping to shape both stronger flocks and sharper agricultural minds.

Dr Morris did not enter the agriculture field intending to become a poultry nutritionist and admits that his interest developed years later. In his interview with the Pepperpot Magazine, he explained that his first step into agriculture began at the Guyana School of Agriculture, where he initially aspired to enter veterinary science. “I started out wanting to become a veterinarian. I went to the School of Agriculture and did a diploma in animal health and veterinary public health, which kind of prepares you for being a veterinary technician or assistant. During that programme, that’s when I kind of fell in love with nutrition itself because I was doing nutrition there as a course as well,” he stated.

After finding his passion, Dr Morris took the next step with new determination, pursuing a degree in agriculture at the University of Guyana. From there, he delved deeper into nutrition and eventually specialised in poultry nutrition. Today, he is part of a growing field of agricultural nutritionists—and one of the few Guyanese in it—but his passion for his work has pushed him even further. “When I had the option to go do my master’s, I focused on monogastric nutrition, which is both swine and poultry, specifically in mineral nutrition. And then for my PhD, I focused a lot more on poultry nutrition and did a lot of work with broilers, layers, and turkeys,” he explained. “I’ve been in animal science for over a decade, but I’ve been a PhD poultry nutritionist since 2020.”

While the term poultry nutritionist may seem self-explanatory, the work of people like Dr Morris is vital—not just in raising healthy chickens for farmers, but in ensuring that healthy chicken reaches our homes and plates. “A typical nutritionist formulates diets,” he said. “I simplify it by saying it’s like making a cake. We have all the ingredients to make this cake that we want, but let’s say we don’t have wheat flour—we may have almond flour or some other alternative.”

In assessing the nutritional needs of poultry, Dr Morris considers a wide range of factors. His work balances both the scientific and business aspects of agriculture, ensuring that chickens are well-fed without putting farmers in debt. “As a nutritionist, there are some key factors we look at—what is available, the nutrient requirements for the animal we’re feeding, and the quality of ingredients that go into the feed. Every animal has various nutrient requirements at different phases of their life, so we make that ‘cake’—the feed—based on their nutritional needs,” he said. “We use a least-cost method, meaning we want to use low-cost, good-quality ingredients to produce good-quality feed. Feed is the biggest expense in production, so efficiency matters.”

While agricultural nutritionists like Dr Morris are helping farmers raise healthy livestock, they still face several challenges. One major one, according to Dr Morris, is that farmers often underestimate how much livestock care depends on proper feeding. He explained that feed accounts for more than 50 per cent of total operating costs. “In poultry production or in any sort of monogastric operation, feed is about 70 to 75 per cent of your total operational costs. I think that’s where some folks get pulled off—not realising that these animals need to be fed, and feed should always be available, especially for broilers. They’re producing meat, so feed should always be available.”

Good nutrition for chickens is about more than growing them fast—the food they eat profoundly impacts the meat, and by extension, the people who consume it. While bigger chickens may be better for the farmer, poultry nutritionists like Dr Morris are equally focused on ensuring the meat is safe and natural, avoiding the use of unnatural steroids. “Some folks may get into poultry production on a small or midsize scale, not understanding all the facts about feed and nutrition. If you don’t have control over your nutrition, you are likely to run into trouble with growth performance, birds meeting the right weight, and even disease challenges,” he said. “The feed and the quality of feed are very important in poultry production because if you don’t have the right nutrition, you cannot grow to meet your true genetic potential. And that goes for anybody or any living thing.”

Another hurdle often faced is the lack of farmer education and in-depth knowledge about the food, additives, and nutrients required for livestock. Speaking to small farmers in particular, Dr Morris urges them to take a closer look at what they feed their animals—and by extension, the nation. “Some farmers do not even know what’s in the feed. They just think it’s corn and soybean meal. They don’t know about the calcium, phosphorus, enzymes, or amino acids, which are critical components of the diet. They should at least have a fair understanding of the quality of the feed,” he said.

However, food is not the only factor that influences livestock health. As Dr Morris explained, there are many other contributing elements—some less obvious than others. Urging farmers to examine all underlying factors, from exercise and exposure to handling and health, he noted, “In most developing countries, we do not have the facilities to test feed quickly to confirm if it has the right levels of nutrients. So nutritionists and feed often get the blame, but there may be other challenges—management-related issues, problems when the chicks were hatched or transported, or improper brooding.” He added, “Brooding is that first phase where you try to create an environment like what the mother of the chick would provide—heat, comfort, water, and everything else. If that is not done correctly, you run into problems later on.”

Ventilation and humidity are also crucial factors, Dr Morris explained. Rearing chickens to their full potential requires balance and consideration for changing conditions. “If it’s too humid, some folks may feel that because it’s cool outside, the birds would be comfortable, but that cool air can be trapped in the barn, causing wet litter where microbes and pathogens multiply. Common diseases like coccidiosis and chronic enteritis can result in mortalities,” he said. “You also need to know when the birds are supposed to be out. If the birds are generally supposed to be finished in six weeks, you don’t need to have them beyond that. The bigger they are, the more feed they need, so you lose money.”

While he is working to ensure farmers raise healthy chickens, Dr Morris is equally focused on raising a new generation of agriculturists. “I strongly believe that agricultural education is one of the best investments anyone could make. My passion is people and human development. This is just stuff I do on the side, with my own resources,” he said.

For the past several years, Dr Morris has served as a mentor and guide to many young Guyanese seeking to pursue degrees in agriculture abroad. “It started during my master’s programme, mentoring minorities in STEM at the University of Missouri. From there, I started doing similar work with Guyana and UG. I have friends who are lecturers at UG, so I’d have them help me select students who wanted to go to grad school,” he said.

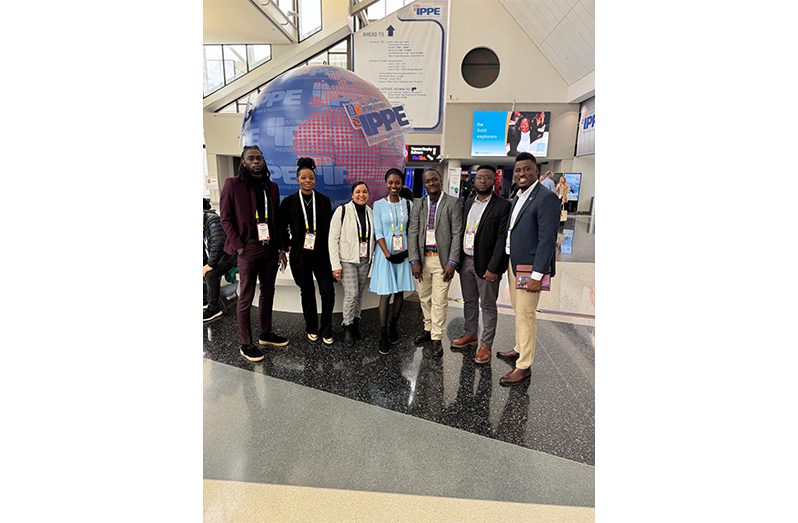

Dr Morris mentors young minds through scientific research, writing, and conferences—all aimed at developing a new generation of skilled agriculturists. “I mentor them in reading scientific articles and research skills, then bring them up to the US for conferences so they can see students presenting at graduate and undergraduate levels. Based on their interest—food safety, nutrition, genetics—I connect them with professors at different universities,” he shared. “Over the years, I’ve had quite a lot of students pass through. Recently, I had five students at Auburn University, two at Mississippi State, and one at the University of Georgia. There were two others at UGA who are graduating this November. They did their final-year research there and are both starting graduate programmes soon.”

From a young Berbician to a leader and mentor in his field, Dr Morris has become an advocate for the opportunities that come with studying agriculture. While the sector may seem like simple farming or livestock rearing, he believes it is much more—a foundational pillar of national development and a path to personal growth. “For me, it’s about leveraging my network within academia and the industry to tap into the talent we have in Guyana, whether from UG or GSA, and giving them exposure to what’s possible in agriculture and animal science,” he said. “It’s a really good feeling to see people tap into their potential and passion because I know what it did for me, coming from Berbice. I was always dreaming big, but I know what it did for me and my family, and I know what it can do for them.”

.jpg)