AS a child, I was introduced to the beliefs that enveloped the world of the last days of British Guiana and early Guyana.

Story time occurred occasionally in my father’s workshop up the coast, with his friends like Uncle Mosche, the masquerade band flautist, who had an archive of explanations concerning the masquerade band. He urged me that until my maturity—marked by becoming a father—my first honour would be to keep secret what I was told. But that was on the East Coast.

Years later, I had filed away most of what I had learnt then, not knowing that I would one day witness, for the first time, an incident that had only ever been described to me in gyaff. In West Ruimveldt, where I lived, a younger brother was standing next to me as drums beat in front of our range. Suddenly, he did a somersault and, supported by his arms, began dancing upside down; at one point, he was balancing on his head. It was incredible.

Someone came back from the group that had left hurriedly. We all had names for what was happening, but couldn’t do anything to change it. The ‘Front Road’ didn’t have all that housing back then. The dark trench water kind of awakened him, but the brother couldn’t recall anything afterwards. We were just glad he was still with us.

A few years ago, I bought and read a book titled, The Jumbies’ Playing Ground, by Robert Wyndham, which focused on Afro-Creole masquerades in the Eastern Caribbean. I then realised that our masquerades had a different root from those in that part of the Caribbean. Though we had adopted some colonial instrumentation, there were still unique elements that were ours.

- J. Seymour had published a book in 1975 titled, Dictionary of Guyanese Folklore (and please don’t ask me—I’m not lending any of my country folk a book).

My late great-aunt told me about the declaration of Cumfa, a festival common to Charlestown, Albouystown and La Penitence, in honour of King O’ Cumfa of the Congo. In the 1930s, those days when the Sussex Street trench was black water, many mysteries would emerge, though not without symbolic meaning.

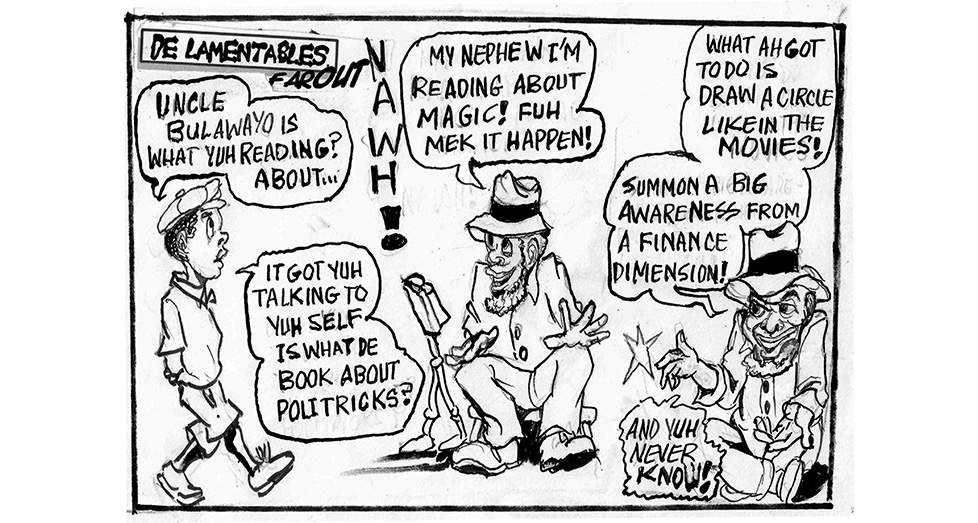

I can well recall meeting the late illustrator Seymour. I had questioned him about the character ‘Big Mama’ and why he had demonised her. He explained that he wouldn’t have been able to get published otherwise, since the Church held great influence and could suppress anything it disliked. It must have been difficult back then. Today, it isn’t smooth running either; the arts’ potential still seems not quite understood. But everything can be comprehended if the people involved are allowed to ask and answer a few questions themselves.

We may, in conclusion, try to avoid the predicament of our CARICOM zone, as cited in Al Creighton’s June 20, 2021 interview with Harold Bascom, The Impoverishment of Caribbean Writers and Creative Souls. My addition, in closing, is that creative folk have a clear perspective of the bridge before us. We’ve already paid the troll’s fee.

.jpg)