I WAS brought up in a home that cannot boast of being rich, but one that addressed its needs within an environment of familiar customs—such as planting fruit trees and making Creole beverages, done out of habit despite the threat of fruit looters, mostly neighbourhood children. As we grew up, the habit of eating fruit and greens was common. My family was spread around several areas in Georgetown and some on the coast. Adventures like “bush cook” had brought a later commonality with many young working-class youths exposed to this mainly rural activity.

But what else the bush cook embodied was that it was mainly a male thing—of course, there were always tough girls who defied any young male’s imagination of control, or who refused to sit next to them and play “big boy” uninvited without delivering a well-landed punch. Thus, everything had its rules that demanded obedience or prolonged shame.

One of the things then was that one could buy or plead for a fruit and enjoy it willingly. Today, it’s different. Sometime last year or the year before, I bought a parcel of tangerines. I came home, missed lunch, and had a tangerine—an old habit—then took a bath. I was tired, but when I awoke, my wife and daughter told me that something was wrong. My lips were swollen. They provided a tablet that was guaranteed to ease the swelling, and it did. They assured me that the fruit had been sprayed with chemicals to hasten its ripening. I have written articles on this subject over the years since this act was introduced here.

So, I decided to visit the salespeople. A young individual insisted that they also bought fruit from other farmers. I didn’t accept this because of what she had told me before, when I enquired about the fruit they had on display. She had then told me that they were producers, then reversed on my second complaint.

So, I decided to visit the Ministry of Agriculture. Unfortunately, I arrived around lunchtime. Some hours later, a relative working there came out to inquire. Realising that I was caught between lunch and probable meetings, I waited a few hours but reluctantly left.

I must again highlight a judge in India whose assessment of fruit ripening I found compatible with my own. Acting Chief Justice Dilip B. Bhosale and Justice S.V. Bhatt addressed the fruit traders who use carcinogen calcium carbide to ripen fruits, calling them “worse than terrorists.” Calcium carbide is a chemical compound whose two main products—acetylene, a colourless gas widely used as a fuel, and calcium cyanamide, used as a fertiliser in agriculture—are extremely harmful to the human body. This article can be found in The Times of India.

This situation requires thorough examination, as more severe damage to the body can occur. In a country where fruits rank high in snack and food choices, a greater emphasis should be placed on this.

In closing, I would like to refer to a troubling incident that occurred outside a client’s premises while I was visiting, where I met a minibus driver who also frequented the client. He looked withdrawn, so I greeted him. He told me that he was selling his minibus—it was almost new. I shrugged, almost implying “why?”—and he explained that his brother was a farmer who worked in the backdam of the district he was from. His brother would bring fruits for his family. Now his wife was diagnosed with cancer. Selling the bus was one way of helping his household. His brother confessed that he had followed the trend of spraying artificial fruit-ripeners on his fruit. This was not intentional.

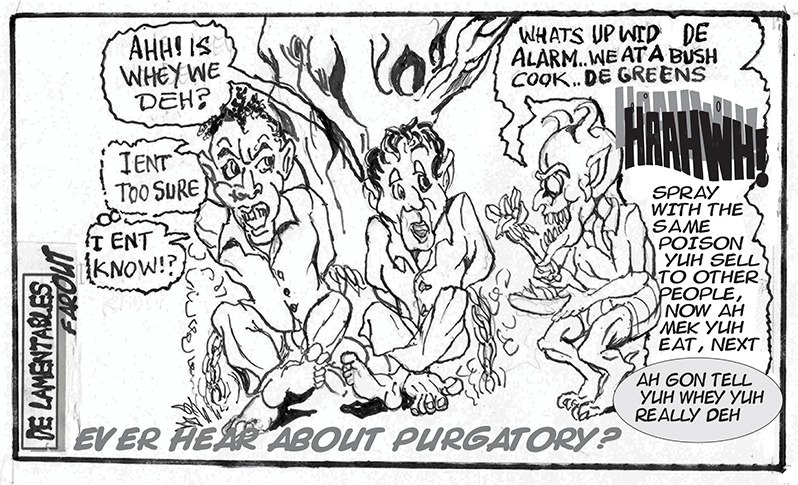

This has been a long-standing problem linked to economics. I recall an article by Leonard Gildarie, dated August 14, 2010, on page 16, where a supplier urged the blacklisting of farmers who use illegal chemicals. I have covered this topic several times, even developing a comic book for NARI—all in respect to institutional response.

.jpg)