THE majority of the planter class viewed the efforts of the emancipated African descendants with envious contempt.

The business of plantation success lay with unpaid, or to be more specific, “cheap labour”, and much of the indentured labour, specifically the Madeirans, were physically inept for plantation work. They died quickly in the field. That group, it must be noted, were not colonised citizens of the British Empire. To this day, we remain unsure of the real reason for their indentured journey, although some causes have been suggested, such as starvation in Madeira. Thus, some former slaves with in-depth training in the sugar production process were paid. But in this age of lawlessness and spite, the platform was far from fair and humane. Towards the emancipated, their livelihoods and ambitions were targeted at every step, with the intent to retain their dependency on the sugar plantations.

With induced systems designed to frustrate the once-plantation labourers, they were already paying taxes for items that the planters were not paying for. The plantocracy, coupled with the local colonial administration, insisted that each emancipated income earner must purchase a licence to exist. All this was conceived to direct them back to servitude on the sugar plantations, servitude that was construed of meagre earnings. It was known that some freed slaves were employed on the plantations with reasonable pay, but these were technical people who managed the very machinery of sugar production. The other plot was to encourage the weaker Madeirans to intercept the earnings of the collective Afro-community’s initiatives.

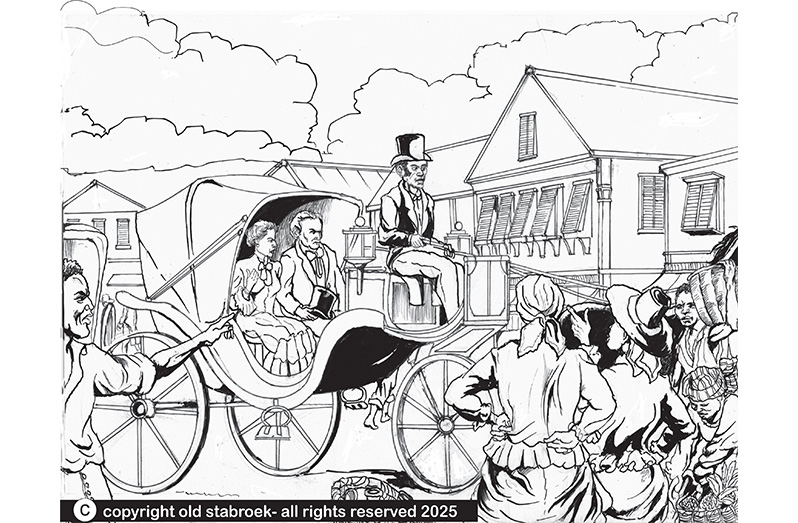

However, by the end of 1846, the planters were faced with external problems stemming from the very nature of their product. The bankruptcy of more than a dozen West Indian houses of long standing had had terrible effects throughout British Guiana. The comparative inequality of taxation was to be borne by the separate classes, and the injurious effects of both on the standard of living of the labouring population led to widespread dissatisfaction. It was difficult for Governor Light to confirm that the “temper of labourers is soured”. He admitted that it was not at all uncommon for remarks not of the most civil kind being made by groups of Creoles on meeting carriages and horses of officials, to the extent that the people were taxed to pay for such luxuries. This admission accepted that discontent was rife, widespread, and openly vented.

The fact that excessive taxes were levied to fund indentured labour to sustain cheap labour costs led to acts of arson against the planters. In many areas, the Creoles rejected working for the planters and reverted to their own farming grounds, but there were always taxes and unfulfilled government commitments to drainage, etc. Such was the post-emancipation confrontations and mood at most times.

What became surprising were the paths to education and engagement in cultural farming and cottage industries that were developed in the interest of survival, engaging thinkers across other groups who offered similar cottage industries.

.jpg)