In the remote community of Baramita, Matarkai Sub-District, Region One (Barima-Waini), 27 women recently celebrated a significant milestone after participating in a six-month literacy and numeracy programme aimed at transforming their lives through education.

The women and girls, many of whom had little to no formal education, learned to read, write, spell, and count—empowering them with fundamental skills to navigate everyday life.

During the course, participants mastered essential literacy skills such as writing their names, spelling basic words, and crafting simple sentences.

They also learned numeracy skills, including counting from 1 to 100. The newfound knowledge has greatly enhanced their ability to engage with essential social services in their community.

The literacy and numeracy programme was designed to address a critical gap in basic education for women and girls, giving them the confidence and tools to manage tasks such as reading signs, filling out forms, and interacting with service providers.

For these 27 graduates, the ability to read a calendar, recognise the days of the week, and understand the months of the year represents more than just academic achievement—it is a step towards independence and self-sufficiency.

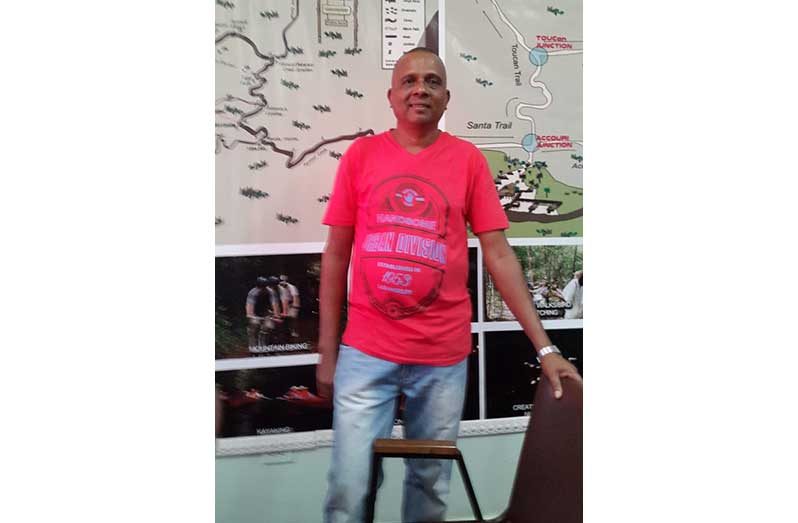

One of the facilitators of the programme, Bissoonnauth Bacchus—a native of Baramita Central—told the Pepperpot Magazine that the literacy and numeracy programme for women and girls was held at the Baramita School in 2024, with support from the Village Council.

He reported that it was for school dropouts and older women who had no formal education, and they conducted sessions in two batches.

The current headteacher, Audrey Williams-Massiah, and Bacchus himself tutored the girls and women—15 per class, though some dropped out and didn’t graduate.

Bacchus added that it was time well spent, noting the transformation of persons who were unable to read and write from letters and eventually managed to pronounce words, which was the highlight of the initiative.

He stated that at first, it was very challenging because of the language barrier—most of the locals still speak in their Carib dialect and are non-bilingual—but they were committed to learning.

The tutor, a former educator, pointed out that the girls and women learned over time and even completed their homework. He was very pleased with their effort.

Bacchus, a local of the Essequibo Coast who resides in the far-fetched village of Baramita, related that his wife, a native of the village, was roped in to assist in translating since she is from the Carib tribe—the majority of Amerindians in that area.

He told Pepperpot Magazine that he did what he could to build their confidence, and they blossomed from being completely shy and introverted into people who were able to read and write for the first time in their lives.

Bacchus revealed that Food for the Poor (FFP) Guyana provided the materials for the programme, which was well received.

In 1998, he was the headteacher at Baramita School and was often the lone educator there. In 2000, he realised the need to qualify himself and enrolled at the University of Guyana (UG), where he pursued a degree in educational administration and passed with credit.

However, upon completing his higher education, Bacchus returned to the community to teach for 18 years. He was a teacher for much longer, having spent 30 years in the noble teaching profession.

The father of three reported that , after retiring as a teacher, he worked for two years as a probation officer and was also part of many educational programmes and volunteerism initiatives with the Village Council and other agencies.

Bacchus added that the Village Council has a multi-purpose building, which was gifted by FFP Guyana, and that is where most of the community-based initiatives are held.

He disclosed that Baramita School has moved from being a Grade E school to an improved Grade B school, with an annexe housing the secondary department about two kilometres away from the main building, which accommodates the nursery and primary sections of the school, outfitted with teachers’ and headmistress’s quarters.

The Baramita School benefits from the government feeding programme, where a kitchen provides breakfast and lunch for learners five days per week.

“As an educator, I loved my job. I was one of the few who, after completing UG, returned with a degree to Baramita Village and, as a coastlander, gave my service. My main focus was building human resource development among the people,” he said.

Bacchus noted that Baramita is an exceptional place where the natives have never lost their true identity. The majority speak in their own Carib dialect and are not bilingual, so there is always a language barrier.

He revealed that in Baramita, there are 20 satellite villages and some smaller villages with locals who do not speak English or even broken Creole.

.jpg)