(BBC) – WAS a Grammy-winning rapper singing about crimes he committed or simply expressing himself as an artist? New legislation in the US sets guardrails on the use of lyrics as evidence in criminal cases.

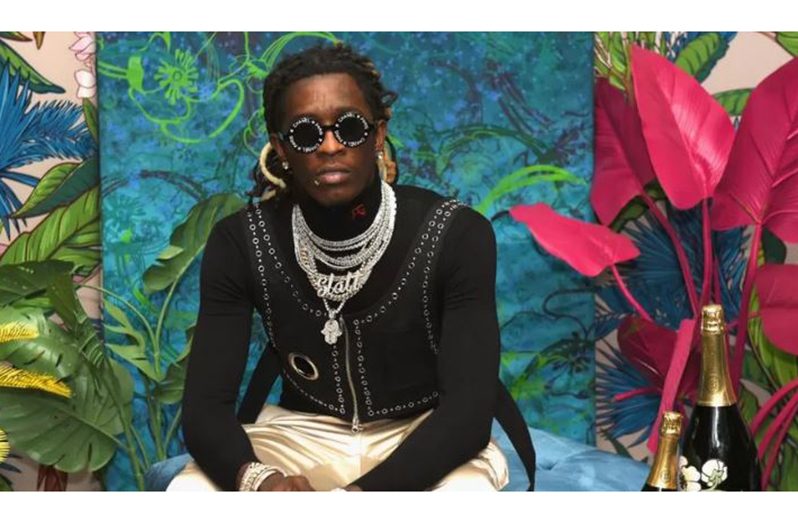

Under the alias Young Thug, Jeffery Lamar Williams, 31, has sold more than 2.5 million albums and been hailed as “the 21st century’s most influential rapper”.

But prosecutors in his native Atlanta are not impressed. In May, Mr Williams was arrested on racketeering and gang-related charges and has been in jail since. This month, he was denied bond for a third time.

Prosecutors allege that Young Stoner Life (YSL) Records, the rap label Mr Williams founded, is the front for an organised crime syndicate responsible for “75 to 80% of violent crime” in the city.

Part of their evidence to make that case? The lyrics that have garnered Mr Williams legions of fans.

“I never killed anybody but I got something to do with that body,” he proclaims on the 2018 song Anybody, for example. “I told them to shoot a hundred rounds.”

Listeners of rap music rarely flinch at the genre’s predilection for violent references – but rap artists in courtrooms around the country have been finding out for years that judges and juries might.

Rap lyrics have been used in more than 500 criminal cases around the US over the past two decades as evidence.

Now, a new bill in US Congress aims to stop the practice, raising questions about free speech, artistic expression and race.

The Restoring Artistic Protections or Rap Act was introduced last month by Congressman Hank Johnson, a black Democrat from Georgia, who argues that the use of rap lyrics as criminal evidence is racist.

“Bringing rap lyrics into the fact-finding process oftentimes is just another way of creating prejudice and bias in the minds of jurors and judges, and that’s wrong,” he said.

Advocates for the rap industry agree, and say that the art form is routinely under assault.

“We’ve looked at this for decades and no other fictional form, musical or otherwise, is being targeted this way,” said Erik Nielson, a professor at the University of Richmond who studies the relationship between black artistic expression and US law.

And according to his 2019 book, Rap on Trial, co-authored with former public defender Andrea Dennis, the practice of using rap as criminal evidence is growing.

“By and large, it is amateur rappers, those without any real name recognition, who generally lack the resources they would need to mount a vigorous defence,” he said.

“But we’re starting to see that police and prosecutors have become more emboldened.”

Of the more than one hundred cases Mr Nielson has consulted on, he argues that none were obvious cases of a rapper chronicling criminal activity or mapping out crimes they’d like to commit.

“They are stock lyrics that have been uttered many times by platinum-selling artists, but prosecutors do not characterise them that way,” he said.

By cherry-picking lyrics that are threatening and prejudicial, prosecutors can “play upon, but also perpetuate, the stereotypes that many jurors [and judges] hold about the criminality of young black men”, even if there is no physical evidence they’ve committed a crime, said Mr Nielson.

In the case of Mr Williams, prosecutors in Fulton County, Georgia have argued that YSL, despite producing Grammy-winning talent, is not a straightforward business, but a street gang affiliated with the national Bloods gang enterprise.

In an indictment in May, the district attorney’s office charged 28 YSL artists with conspiracy to violate the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organisations (RICO) Act – famously used in mafia prosecutions – and tied the men to a series of felony offences, including murder, armed robbery and carjacking.

Cited throughout the charging document “in furtherance of the conspiracy” are the rappers’ lyrics in dozens of songs.

Many of the accused have vehemently denied the charges, with Mr Williams’s long-time attorney Brian Steel repeatedly saying his client has “committed no crime whatsoever”. Fulton County prosecutors did not respond to the BBC’s requests for comment.

Mr Williams complained to fans in June in a message from jail, saying: “You know, this isn’t about me or YSL. I always use my music as a form of artistic expression, and I see now that Black artists and rappers don’t have that freedom.”

But prosecutors who have been able to deploy the strategy say that lyrics should be fair game when they have a clear connection to a particular case.

When prosecuting a local artist, Darrell Caldwell, for criminal charges in Los Angeles in 2020, county authorities were able to use footage from a music video in which the rapper shows a gun used in a crime to implicate him – though he was earlier acquitted of a more serious murder charge, he pleaded guilty to shooting a gun from a vehicle.

“The rap video itself had evidentiary value that helped us solve the case,” said Phil Stirling, a former Los Angeles County deputy district attorney.

Mr Stirling conceded that unfair verdicts may result from an over-zealous prosecutor or an unfair judge, but rejected the notion that using lyrics as evidence is “racist”.

“There are murders that occur in the rap world because of connections with gang members,” he said. “The victims are [mostly] black and brown. If [the use of rap lyrics] is racist, let’s do away with it. But who suffers in the end?”

There have been some past attempts to limit the use of rap lyrics as evidence in criminal trials.

Eight years ago, New Jersey’s state supreme court overturned the attempted murder conviction of aspiring rapper Vonte Skinner.

Prosecutors had used Mr Skinner’s lyrics as evidence in the case, which the Supreme Court ruled 6-0 had the effect of “poisoning the jury”.

Lawmakers in California and New York have also advanced bills this year to bar the use of lyrics in state courtrooms.

The Rap Act would be the first measure to do so on the federal level, though it is still too soon to tell whether it will eventually become law.

But regardless of its success or failure, the jailing of Young Thug has given momentum to artists pushing for change.

Michael Render, better known as rapper and activist Killer Mike, is among several high-profile artists who have featured Mr Williams in their music since his indictment, also arguing that the arrest fits with a racially prejudiced targeting of rap music.

“If you were writing a movie, and something happens that’s coincidentally similar to the movie, I’m not going to charge you and your whole movie set as a cartel,” said Mr Render.

On the other hand, “rap is a low-hanging fruit and an easy one to target because most of society is not going to fight for the rights of those that they consider beneath them or an art form they consider below them.”

“Hip hop is art, it is literature, it is poetry, it is free speech, it is journalism, and it should be protected as such,” said Jamaal Bowman, a congressman whose district includes the Bronx, NY, the birthplace of hip hop. “It should not be criminalised.”

.jpg)