by Terence Roberts

The overall value of painting as an art object is that it can influence our real life. Of course, all the other arts can too, but painting (and drawing) is the first visual art of the widest influential scope.

What a painting can do by a visual manifestation of the physical and mental remains unmatched by all the other arts except the art of cinema.

The importance of nature’s atmospheric light to painting led the best European painters since the 17th century to chase after summer and Mediterranean scenes and tropical landscapes all over the world. All that outdoor nudity we see in the sumptuous paintings of Bosch, Rubens, Jordaens, Boticelli, Romano, Tiepolo, Renoir, Gaugin, Picasso, Matisse, or Dufy, cannot exist in cold, temperate settings.

Dismissing early religious dogmas and prohibitions, then freed by the 17th century’s Enlightenment philosophy, outstanding European painters began to explore the importance of the tropical to the earth’s continued fertility, and the necessity of sensual human pleasure.

Tropical values in painting began to emerge as a vital human value beyond racial obsessions, or the difference and diversity of races, in early 16th century paintings like The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch, and Rustic Banquet by Giulio Romano.

By the 17th century, the sumptuous paintings of Rubens and Jordaens especially, with the nudity of white and non-white in obviously warm, sunny, outdoor festive environments and bountiful harvests of fruits, vegetables, cakes, wine, music and dance, lead us to wonder if such European paintings at such a time, were the naïve expressions of artists unaware that European explorations in the Oriental East, North Africa, and the Americas, would lead to travesties of their culture towards others.

However, the first written reports from these tropical areas by Columbus, Vespucci, Marco Polo, Montaigne, Sir Thomas More, even Sir Walter Raleigh, did not describe much less than tropical paradises, despite confronting what seemed shocking native customs to the writers.

European painters from Italy and Flanders, like Romano, Tiepolo, Bosch, Rubens, Jordaens, Van Heemstreck, were quite learned, literate men influenced not only by reading the Bible, and ancient classic Greek and Roman texts with their descriptions of the semi-tropical Mediterranean, but by such early reports on non-Western lands.

Even more important in the cases of Rubens and Jordaens, the amazing new philosophical reasoning and analytical descriptions by Descartes, whose “Discourse on Method” and “Passions of the Soul” proved the equality of all human beings as manifestations of God on earth, would become an influence on such painters, who would have become aware that the various European empires which succeeded those first explorers in these far off lands hardly believed in any ideal tropical paradise their forerunners had discovered there.

We can say that the ideal tropical scenes and topics these painters projected, even if aware of the inhuman development of colonists there, challenged and vetoed such unsavoury actualities with the creative possibility (as Descartes correctly theorised) of a better, more beneficial egalitarian and civilised future, preserved in their amazing canvasses, which today are undisputedly of more benefit to the behaviour of mankind than the historical atrocities of past European colonial empires.

The 19th century saw French writers and painters voyaging to nearby tropical North Africa, the far off South Seas tropical islands, and the Americas. Flaubert visited and wrote about Morocco. Nerval wrote ‘Voyage to the East’ based on his sojourn there. Baudelaire’s mistress in Paris was an African beauty who influenced some of his most imaginative “tropical” poems.

Delacroix followed a French diplomat to Morocco and Algeria and painted a stunning book of watercolours filled with sensitive tropical light and shadow.

Gaugin, perhaps the most famous of all European painters, totally rejected France and his prestigious job at a bank there, and fled to the South seas to create art history with some of the most sensual figurative tropical paintings the world has ever seen.

From all such creativity with paint, a human value, added to an artistic value, began to emerge. It was not simply the natural landscape and sunshine of the tropics that were important, but the human lifestyles and their native cultures which existed on it.

By the early 20th century, tropical influence became a most vibrant and important approach to form and content in abstract painting. Traditional figurative painting which developed in 16th century Western Europe, especially during the Renaissance with its invention of perspective and anatomical proportion, is also attached to certain types of western European architecture, climate, landscape, even clothing.

But what if the artist absorbed a new tropical environment where structures were less rigid or straight and their material changed colour under the sun and rain, and the sky was dazzling, and the earth dusty, and all kinds of strange profuse vegetation existed?

Paul Klee’s watercolours and drawings influenced by his sojourn in North Africa early in the 20th century produced masterpieces which developed abstract painting as an intense focus on the effects of the elements. Klee’s tropical cities in the scorching desert, their roofs, doorways, vegetation etc., began to melt and fade into each other under the influence of their tropical atmosphere on painting.

Yet they still find balance, because the painter composes art, not imitates what he sees. Klee’s colours are soaked in a heat-wave of tropical values. Their surfaces affected by the elemental became paintings which discipline the mind by absorption.

Cezanne’s watercolours offer the same value, but are of less harsh Mediterranean light, and are far more important to the development of tropical abstract painting than his oil paintings.

His watercolours of fruits, bottles, bowls, tables, drawers, trees, table cloths etc., shimmer with multiple shifting free hand outlines, and soft melting molten tones, rather than rigid paint application. Cezanne’s fruits are ripe with sunshine, but not rotten. His move to France’s hot Mediterranean summer countryside locations inspired such paintings.

Picasso’s unique genius in painting largely rests on his multiple use of tropical sources.

Born in Malaga’s port on Spain’s Mediterranean Andalusian seacoast near North Africa, Picasso like most of the leading European founders of abstract painting (such as Klee, Cezanne, Matisse, even the half Asiatic, Kandinsky from Russia, who was influenced by his travels in Tunisia), had little interest in art influenced only by European racial ancestry.

His famous Cubist paintings show the background influence of small unfinished square and oblong Moorish tiles melting into each other in tones of earth brown and grey.

Such influences from Spain’s long North African colonization were Picasso’s birthright, which he later simply extended towards an interest in central African tropical sculpture and assemblage.

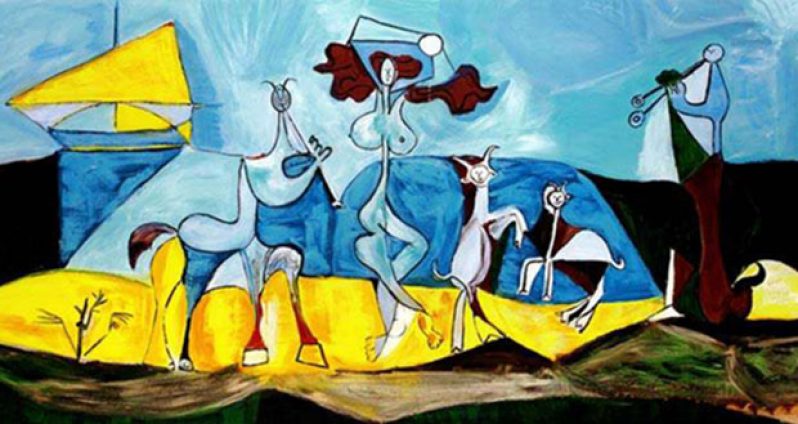

Picasso’s famous stay at Chateau Grimaldi on the sunny Mediterranean French Riviera, produced not only brilliantly painted ceramic plates of profound tropical qualities, but a stunning series of tropical paintings, three of which are Night Fishing at Antibes’ (1939), The Joy of Living (1946), and Ulysses and the Sirens (1947), introduced one of the greatest values of tropical abstract painting: bare white or blank space representing the pure light of the sun.

.jpg)