Indian Indentureship Exhibition at the National Archives

By Gibron Rahim

“IF you don’t know history, you don’t know anything. You are a leaf that doesn’t know it is part of a tree.”

These words are attributed to the late author Michael Crichton. The truth in them is immediately evident. A people uninformed of their history fail to learn from it or to even recognise their place in it. This is one of the lessons that can be gleaned from the recently-held Indian indentureship exhibition at the Walter Rodney Archives.

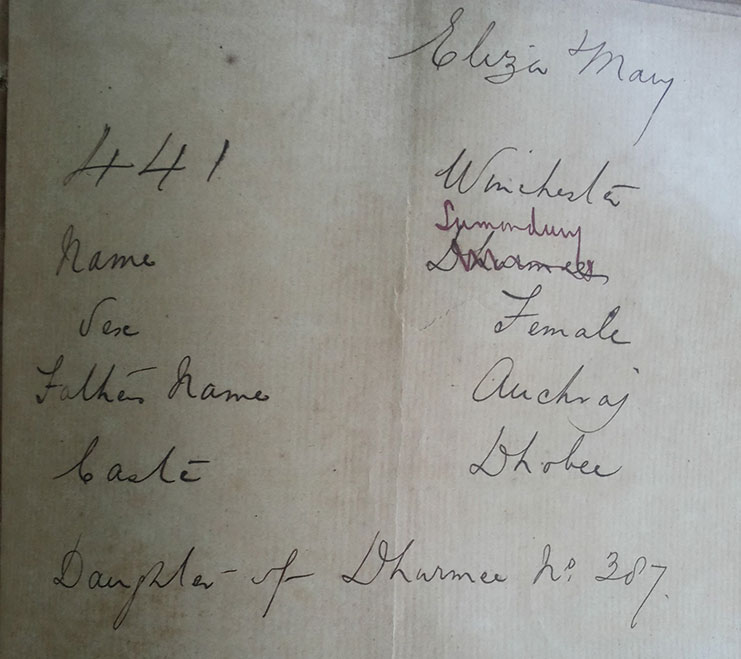

Two attraction at the exhibition immediately drew the eye to opposite sides of the room upon entry. To the left were original emigration documents of indentured Indians, all remarkably well preserved. On these yellowed and aged papers were details about men, women and even children who left India for British Guiana. And to the right were logs where information about the indentured labourers on the estates was recorded. Family relationships, births and deaths were all noted. Carefully placed around the room were artifacts and models that together told the story of the indentured Indians.

The documents ensure remembrance of ancestors long gone. They also stand as a reminder of the harshness of life on the sugar estates. Ms. Karen Budhram, Senior Assistant Archivist at the Walter Rodney Archives, kindly took the time to speak with the Pepperpot Magazine and to elucidate the details of the lives of indentured Indians on the estates. The information she shared carried personal significance for her – most of the artifacts and documents on display were from Karen’s ancestors. However, the stories she uncovered through her research tell us that there were common threads in the lives of the indentured Indians.

Dying at a young age was one of the most unsettling discoveries of Karen’s research into her ancestors. Karen noted that many of her female ancestors died in childbirth while pneumonia claimed the lives of the men. A look at the estate logs revealed that early death was more common than not. Pneumonia, cholera and dysentery were all common in the harsh and unhygienic conditions on the estates.

The indentured Indians were allowed to keep their culture but it was a choice that came with a cost. Karen explained that, while they could keep their Indian names and give their children the same, the churches were in control of the schools. Immigrants who wanted to educate their children had to give their children Christian names.

Marriages were only considered legal if they were conducted by a pastor. It was not even possible to register marriages on the estates. She said that in most cases, those who wanted to register their marriage had to travel all the way to Georgetown. This required time and resources that the immigrants did not possess. And they were bound to the plantation for a period of 10 years unless given permission to leave by their masters.

A SEARCH FOR IDENTITY

Karen’s examination of the history of her ancestors was part of a personal journey for her. She explained to the Pepperpot Magazine that she began her search for answers when she found herself experiencing an existential crisis a few years ago. “I guess I was searching for my own identity,” she said. She wanted to connect with herself and her ‘Indianness’. She felt ostracised from her family since she married someone who was not of Indian descent. Her search was partially motivated by the hope that she would find instances where her ancestors had challenged tradition.

The search for answers bore fruit. “Their lives [in British Guiana] were different from their lives in India,” Karen said. “When they came they had to change and adapt.” She wanted to explore that experience of adaptation and moving away from tradition. She uncovered clear instances when her ancestors married across caste system lines. Some of Karen’s ancestors were ‘chamars’, a part of the group known as ‘dalits’ or ‘untouchables’ who exist outside of the caste system and even today struggle for their rights in India. Yet, as an instance of intermarriage, Karen’s ‘chamar’ grandfather married her grandmother who was descended from a Brahmin (a member of the highest caste) pandit.

Karen came across innumerable stories just from her research of documents and even from the oral history associated with some artifacts. This included one of her ancestors having been born on one of the boats on the way over from India. She was even able to construct a family tree (which was on display at the exhibition) that spanned generations.

UNANSWERED QUESTIONS

Yet, though she uncovered much, Karen was also left with many unanswered questions. Three women among her ancestors came over on the boats unaccompanied. Nothing she found could tell her the circumstances that led each of these three women to British Guiana. One of her ancestors travelled over all by himself when he was just eight years old. Among the artifacts on display was a short sword. The story told to Karen is that one of her ancestors fought in a war in India.

Besides learning about our backgrounds and how we ended up where we are, one of Karen’s realisations from her research is that we as Guyanese have more that binds us together than that tears us apart. “I think when we understand our history, we realise that we have a lot more in common than we have differences,” she said. By understanding that our ancestors all suffered under distinct and cruel systems we can understand each other better.

An individual journey into the history of our own ancestors can begin simply by sorting through old documents or artifacts from grandparents or by hunting down a family oral history. The Archives offer free consultations to individuals looking to research their ancestors. Karen noted that dates are essential to the Archives in aiding the search. Our history may be more within our reach than we realise.

The general office of the National Archives can be contacted at 226-3852 or by email at narchivesguyana@gmail.com.

.jpg)