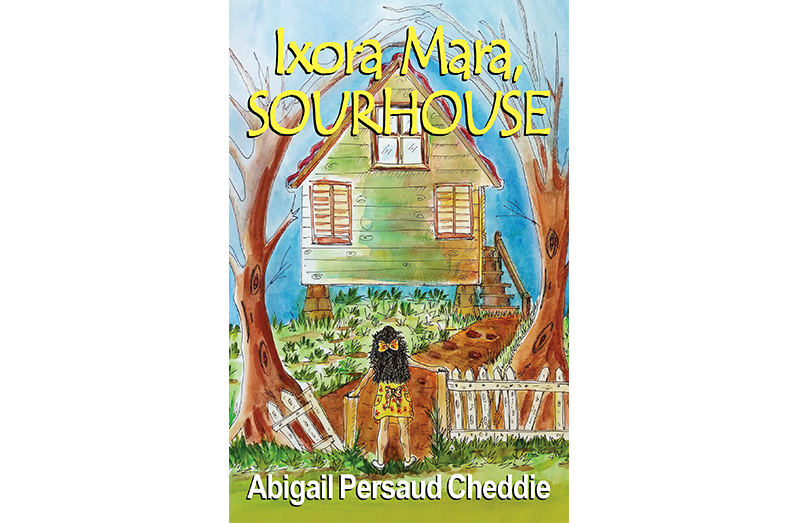

From Ixora Mara, Sourhouse by Abigail Persaud Cheddie

I DIDN’T want to be the sour one. But Ivy said that every village must have its own picklepuss and that I was Peaside Pasture’s because I was better at being sour than anyone else in the village, especially now that old Mr Crapaud – Peaside’s former Resident Sourpuss – had gone away on a plane. It was a role which some other child might have relished, if only for the exaggerated games such a part would allow. Not I. If Ivy thought I was going to fill the vacancy, she was wrong. I was going to be like Peaside’s snazziest soaring star point kite, not some old lime. She’d see. Everybody in the street would see. Everyone in Peaside Primary would see. Everyone in the country and in the whole world would see.

But the lime had already come to me. The first time it appeared in my body was when Suzie said she’d come to my birthday party but didn’t. That day, the lime burned into my stomach. Then it spun and split, shooting juice through my chest and oesophagus and up into my sinuses. After that, Peaside’s vendors swivelled their heads from me to Ivy and back to me, pointed at me and asked Mam, “How come dat one so sour?” They made such a regular joke of it that Mam started telling them to mind their own sour business, please and thank you.

“How you mean they own business sour?” Ivy asked one day. We were in the kitchen emptying baskets, my hands itching from the eddo the vendor had chopped in half and begrudgingly added to the scale to top out the three pounds.

“’Cause everybody sour ’bout something,” Mam said. “Don’t let dem fool you. Sour in they heart. Or in they brains. Or sour down to they lil toe.”

I let an eddo roll back into the basket and looked at Mam’s little toe. I wondered if her nails would glow neon green if her sour ever reached her toes. If your lime juice pulsed through your whole body so that it reached your toes, I surmised, that would be the end of you. For then, all you’d ever be was a big old lime, a Resident Sourpuss. So I resolved to keep my sour thereabouts my stomach and above.

“Oi, pass dat eddo,” Ivy said, elbowing me.

I passed the eddo. Ivy handed it to Mam. Mam stacked it in a bowl on top of the rest and continued her tirade.

“You got to be dead not to have something to be sour about,” she said, “And even then you gon probably still be sour ’cause maybe Saint Peter not lettin’ you in.”

“Letting you in where?” asked Ivy.

“Laurie, what you telling the girls?” said Pap, grinning and getting into the conversation, and ponging the hammer on his thumb.

“Ow, ow,” he said, flicking his hand back and forth.

I watched Pap’s fingernail and imagined its burning pain. I imagined it must feel just like the prickles in my chest when the lime juice started spreading about in my body. The day Suzie said she would come but didn’t.

“Any four or five ah dem could come,” Mam said the week before our birthday. “You,” she pointed at Ivy, “could bring four or five friends, and you,” she pointed at me “could bring four or five.”

So Ivy invited eight friends. Eight.

Who cares, I thought, there was only Suzie to be invited.

So I snatched my skipping rope, skipped barefoot across the street to Suzie’s house, told her about my party, asked would she come please and she said yes thanks she’d come.

“I gon bring you a gift,” she said from her side of the gate.

I was swinging the rope round and round, and the balls of my bare feet bounced on Suzie’s smooth scrubbed bridge.

“True?”

“True,” she said.

I stopped skipping and tootled over to the gate. Suzie smelled like lemony cream biscuits.

“What’s the gift?” I asked, my heart starting up a racket.

She drew closer to the gap between the two paling staves and raised her forefinger to her lips.

“Shh. Gifts supposed to be secret. Mammy gon carry me shop so I could pick it out and wrap it up.”

“Oh,” I said, feigning just the right amount of nonchalance and smoothing out the skipping rope. “Well, awright then. Eleven o’clock, you hear? Remember to don’t forget.”

I started hopping again, thinking about Suzie wrapping shiny paper over something.

“I not gon forget.” She crossed her heart. “Mam said come in time for lunch.”

Food was a burden to Suzie. So in haste, I added “And ice cream.”

“Yellow one?” she asked, sticking her nose between the staves.

I nodded vigorously.

She grinned, and the setting sunlight bounced off the red crystal heart-shaped pendant swaying about the neckline of her sunflower print t-shirt. I turned around and skipped home.

From Suzie’s side of the street, I studied our long low veranda which Pap would soon decorate with the streamers he was hiding in the brown paper bag behind the yam crate. He’d gone to Georgetown and returned with a bag of things that he sprawled on the kitchen table to show Mam. Ivy and I took turns spying at the things through the crack in our bedroom wall. When we rested our eyes close to the wall and stayed steady at the precise angle, we could catch glimpses of the kitchen table. Eventually, we pooled what we’d seen.

Pap had bought party games and red and yellow paper streamers, green paper plates, blue paper cups and a multi-coloured glittery banner that said Happy Birthday. He didn’t know about colour schemes then, Pap. Besides, it was the early nineties in Peaside Pasture. Nobody bothered about colour schemes. Everyone knows about them now though, colour schemes and décor themes, what with all the tasteful sophisticated ones hammered all over the internet – spring palettes, fall visions, winter wonderlands and whatnot. But I’ve had over twenty birthdays since then and Pap still goes on making the house shamelessly kaleidoscopic every birthday’s eve. Even though he has an iPad now that Ivy’s brought him from abroad and even though he knows better because he can just type things into a search bar and get all the answers.

Yes, Pap would decorate the whole veranda, I thought, while I skipped on our bridge and counted my rope rotations. I was almost up to a hundred rotations. I looked back to see if Suzie was still peering through the staves but she had vanished.

When she arrives on my bridge on my birthday, I thought, she’ll gasp at the streamers tacked around the veranda. I spun the rope faster over my head. Eighty-seven, eighty-eight, eighty-nine, I counted. I imagined pinning the cloth tail, which Ganee Gwenny had stitched with dress scraps, to the pink disproportionate donkey which Pappo Harro had drawn in chalk on the ply board by the gate. We’d pin the tail. We’d sip fizzy drinks. We’d play chequers and Suzie’d be mesmerised by the yellow marbles as always.

My feet tangled in the rope. Just when I was up to ninety-seven rotations too. I sucked my teeth, flung the rope over my head and started afresh. One, two … six, seven. Mam would light the seven candles on the cake, and Ivy and I would blow them out together and make separate wishes. Suzie would stand beside me and Ivy’s eight friends beside her, while Uncle Warbin fiddled with his instant Polaroid camera that somebody from ’merica had left for him because they had two, and he’d say, “Smile big. Smile with teeth.”

Again, I tripped over the rope. Our city cousins Lennard and Annie-Lou would come and Uncle Raffie would be forced to dilly-dally, waiting to drive them home, and Mam would wrap a huge slice of cake for Uncle Raffie’s wife who usually sent two presents when everyone else brought one, but who’d said oh goodness gracious that she was allergic to the countryside and the smell of cow dung. Never mind we had no cows.

I skipped faster and jumped higher, getting close to the hearty sky. Mam would wrap parcels of cake too for Junior’s mother and his grampappy, and fill her best bowls to the brim with curry and rice. Then she’d tie everything into a bundle and settle it on Junior’s head while he held it steady with his elbows sticking out as he waddled down the back street where they had no electricity and where he could stub his toe on bricks and send the food pitching into a pothole, as had happened once or twice. Junior’s mother might send us a gift too.

Even Small Spokes, the toddler who lived down the street and who Mam babysat on the half days that his mother went to work, he too would come. After all, it was the babysitting money, the small change, which Mam saved for months that had bought all the party things.

Yes, all of that would happen when my birthday came.

I stopped swinging the rope, stood on tippy toes and filled my lungs with sky. The sun had set and across the street, neighbours flicked the lights on in their houses. Suzie was already at her bedroom window flashing her torchlight, outlining a smiley face on the glass with the light beam. Hers was the only glass window in her house. She shaped a circle clockwise, then added two quick flashes for the eyes and a curve from left to right for the mouth.

I hurried inside to borrow Pap’s torch so I could reply with my own light-up smiley face.

“Come here lemme see if dis dress fit you,” Mam called. She had stuffed Ivy in a dress with frills and was wrestling with the zipper.

“Jus’ now,” I said, looking under the kitchen sink for Pap’s torchlight.

“Come now.”

“Mam, I jus’ have to flash Suzie a—”

“Now.”

She passed a dress over my head and yanked the zipper but it wouldn’t go.

“Psst,” Ivy said. “Oi psst. You look like a yard fowl with two skinny foot an’ a small head an’ a stuffy middle,” she whispered so that Mam, who had gone off to bring more dresses, couldn’t hear.

I sucked my teeth.

“Is you’s a yard fowl,” I said, looking to make a dash for the torchlight again.

“Nope. You.”

“You.”

“You.”

I made a beeline for the kitchen sink, grabbed the torch, ran to the veranda and drew my lighted smiley face on the wall. Then Suzie lit up her window again with another smiley face. Then I drew another. Then she again. Then I.

“Stop wastin’ yuh father torch light batteries and come try on dis dress girl,” Mam shouted into the veranda.

She tugged the pink polka-dotted dressy church frocks down our shoulders.

“Oh thank the good Lord,” she said when she saw that they fit just barely. “Thanks thee good Lord.”

We stood shoulder to shoulder, Ivy and me, looking into the floor-length mirror on the living room wall. The pink polka dots transformed us from the heavy umber of our school uniforms. The polka dots looked like the polished ladies in our story book called Little Sally Hallie Goes to High Tea.

I lifted my chin, wondering if Mam or Ganee Gwenny had pink pearl necklaces like Sally Hallie’s to lend us. Ivy went nearer to the mirror and held out the wide A-lined skirt and twirled.

“Stop twirling before you tear dat dress,” Mam said, then she yanked the dresses off and went to set up the ironing board.

I followed her.

“Mam, you got any pink pearls?”

“For what?”

“Like a necklace.”

“And where I gon get dat from?”

She jabbed the iron at a stubborn collar.

“Your jewel box,” I said.

Mam rolled her eyes and smashed some pleats flat.

But still, I wanted Suzie to see me in a pretty necklace. She had several. Like the silver one with the red heart pendant which she wore just to stand by her gate. In her necklaces she reigned like the head of fairy security, guarding the entrance to her universe across the purpleheart bridge.

So before I went to bed, I sneaked up to Mam’s vanity and lifted the large lid of her precious wooden jewellery box that Pap had made for her with his own hands. It was empty except for a little pale green butterfly pendant, a tiny emerald green turtle brooch and a pair of love knot gold earrings. No pink pearls. No other anything.

I crawled into bed and thought about how I could get some kind of a necklace.

And then, an idea floated to me through the window.

I would string ixora flowers together with a needle and thread just like Mam showed us one time, and I’d make Ivy and me a pair of floral necklaces.

For the next few days I strung flowers in different patterns until the garlands came together at the right arrangement.

And finally, when our birthday’s eve rolled in, Pap hustled about.

He raked grass.

He followed Mam’s instructions on how to set the jello but he almost did it wrong, so Mam clenched her jaw and set it herself.

He arranged the mismatched chairs and stools.

He livened up the streamers.

“Look here,” he said, holding one end of a red streamer and one end of a yellow streamer and gluing them perpendicular to each other. “Looka dis.”

He folded the red strip down, then the yellow across. Then he folded the red up and the yellow across again, but the opposite way this time. Several times he repeated the criss-crossings. Down, across, then up, and across the other way.

“Keep folding like so,” he said, carefully handing over the finished bit to me.

When I came to the ends of the strips, he glued them together. Then he gripped that glued end and gave me the beginning end of the entire folded strip.

“Now hold it and walk backwards,” he said.

As I stepped back, the two streamers, now interlocking, expanded like an accordion stretching several feet between us.

“Whoa looka dat!” Ivy shrieked behind me where she was supposed to be helping Ganee Gwenny press down the ends of cheese rolls with a fork but where she was running her mouth off like a motor.

Every day she gabbered about the people she’d invited. Every single day, round and round like a rotating windmill. She jibber-jabbered about Anahita and Kathi and Lotte and Imani and Adalia and Basmati and Jia. And No-Jo too. But he was coming only because he was bringing his new bat and ball so we could have cricket. And because he, No-Jo, whose real name was Tainojo, was Junior’s cousin and Junior had asked for No-Jo to come.

Every, single, day, and night, like a windmill, the whole house obliged to hear about Anahita this, Kathi that, Lotte so and so, Imani’s clever dog that was good enough for a circus, Adalia’s kitten that bit strangers like a dog, Basmati’s magnificent inherited bangles and Jia’s unstoppable tricycle with the bell that rang like half a dozen bangles clink-a-dinking together.

“Ohh looka dat!” Ivy said again, tugging at Ganee and pointing at the streamer accordion.

Pap grinned and handed me several rolls of crepe paper.

“Try then, accordionise these,” he said.

By afternoon, my fingers were crampy and gluey. When the streamers were ready, Pap tacked them in bellied curves around the veranda’s ceiling.

“Now blow these.”

He handed me and Ivy some balloons and showed us how.

It was not as easy as it looked. I had to thoroughly empty my lungs just for one balloon to live a lifespan. Sometimes I got lightheaded.

Still, I forged ahead, for tomorrow would come and I would tell Suzie everything.

How I had perfected the judgement in giving balloons the right amount of air. Too much would make the balloon either explode and sting your face, or prevent you from knotting it so that it flew out of your hand, kazooing and deflating. Too little would make it smaller than the one before, then they’d be mismatched and ruin the symmetry of things.

I was evaluating my most recent balloon when Suzie appeared at her glass window.

“Suzie!” I shouted across, “Look here.”

I waved one red and one yellow balloon.

She burst into grin and waved with both arms, and cupping her palms to her mouth, she shouted, “Yaay-hey,” into the air.

“Yaay-hey Sue-zaay,” I shouted back.

My feet tingled to skip across the street onto her purpleheart bridge so I could gift her a balloon and explain the important principles I’d discovered. But no, I thought, trying to shush the drumming in my chest. I’ll save everything up for tomorrow and she could have two balloons then — one that I’d already blown and one to blow herself, so she could understand the technicality of the thing.

“Tomorrow?” I shouted across.

“Tomorrow,” she sang into the universe.

That night Suzie’s house went to bed early. All the lights went out and her flashlight faces failed to flicker. Maybe Suzie was sleeping early for my party. Mam had told us too to bed early if we wanted to have enough energy for tomorrow.

So on the night that I was six years and three hundred and sixty-four days old, Pap helped me roll down the mosquito net and waited for me to finish saying my prayers before he turned out the light.

“Nighto Ixie Pixie,” he said.

“Nighto Pap-Pap.”

I pulled the sheet to my chin and waited to turn seven.

In the kitchen, while Mam iced the cake, Madam Ivy’s mouth was still windmilling.