MUCH has been written about what literary critic Frank Birbalsingh, in his book Passion & Exile: Essays in Caribbean Literature, called the “pornographic psycho-sexual” aspects of Edgar Mittelholzer’s novels. This thesis is readily supported with abundant examples from the Kaywana Trilogy, A Tale of Three Places, and, most notoriously, The Piling of Clouds—a novel whose protagonist is, in essence, a paedophile.

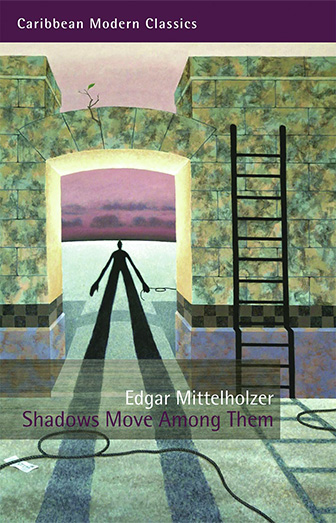

Despite the growing scholarship on this tragic West Indian writer (Mittelholzer committed suicide by self-immolation in 1965), there has been only cursory attention paid to his treatment of the natural world. Critics often mention, with careless brevity, some of the more heated scenes in the Kaywana Trilogy but rarely explore his portrayal of Guyana’s landscape or its profound impact on his characters. Yet, the landscape in Mittelholzer’s novels is as vital as the characters themselves. In his 1951 novel, Shadows Move Among Them, the vivid depiction of nature intensifies the reading experience of this darkly humorous and poignant precursor to the hippie/utopian novel—a work unique within the West Indian literary tradition.

Set in 1937, the novel follows Reverend Harmston, an Englishman educated at Oxford, who relocates his family to Berkelhoost, a remote jungle settlement a hundred miles up the Berbice River in Guyana. There, he establishes a quasi-commune, assuming de facto control over his household and the surrounding Amerindian reservation. He enforces discipline as he sees fit, advocates free love and magic over biblical doctrine, and even dispenses contraceptives. His household includes two daughters—a precocious fourteen-year-old and a promiscuous seventeen-year-old—and two sons. Later, a cousin who is a recent widow suffering from apparent schizophrenia joins them. The jungle environment of Berkelhoost exerts a profound influence on all the characters.

The characters are entirely subject to the power of their surroundings; their actions often appear as capitulations to the forces of nature. The torrential rains, relentless heat, animals, and swarms of gnats, bugs, blights, and bees dominate their daily existence. This landscape encourages the imagination towards unorthodox behaviour. It is precisely this environmental influence that shapes the characters’ conduct. Removed from the civilised metropolis of Georgetown, they behave as creatures of the jungle. Shadows Move Among Them is set against a historical backdrop reminiscent of plantation slave society, rich with the superstitions and mythologies of the local people. Berkelhoost is “a place where the slaves ran around and massacred their Dutch masters.”

Logan, an Amerindian “buck” (as referred in the novel) and notorious mischief-maker, embodies the community’s belief in the supernatural—jumbies, Dutch ghosts, and malicious spirits. In this setting, the Reverend disciplines disobedient Amerindians by chaining them to trees at night or poisoning those who remain stubborn, as part of his so-called “programme of discipline.”

As the Reverend himself acknowledges, “This environment, coupled with our religion, tends to stimulate our imaginations to unorthodox behaviour.” Religion is honoured more in the breach than in observance; simple rituals such as saying grace at meals have fallen by the wayside. The Reverend does not hesitate to announce from the pulpit the arrival of a new batch of prophylactics. It is the environment that holds true sway. The creed of the church he created embraces “Jesus among men, the King of Dreamers, creator of many lovely parables,” believes in “the Bible but only as a book of lovely legends,” and values “hard work, frank love, and wholesome play always spiced with make-believe, in the basic Christian way of living” (pp. 138–139).

Freed from metropolitan orthodoxy, the characters indulge their fantasies. The overwhelming cause of their behaviour is the influence of their environment. Nature, more than nurture, shapes the inhabitants of Berkelhoost. Mittelholzer is explicit about this. In Shadows Move Among Them, nature symbolises the primal needs of the flesh—a recurring motif throughout the novel. “In Berkelhoost the Flesh is powerful, and the devil lurks in the shadow of every twig” (p. 119).

This is how nature affected the Reverend, according to his young daughter Olivia:

“Years and years ago—before I was born—Daddy had a dream about a pretty Buck girl on the Reservation, and nine months later Osbert was born. Mother nearly left him; it upset her so much, but he managed to persuade her that he was blameless; it was the local influences that had caught him napping” (pp. 119–120).

These “local influences”—myth, dreams, make-believe, ghosts, and spirits—are inherent in Berkelhoost and serve as justification for every human action. Nature here is not so much personified as allegorical: the landscape represents ideas and ideals, freedom perhaps foremost among them. Yet the jungle is also curative, sometimes menacing, reflecting various facets of the characters themselves.

For Gregory, the young widowed English cousin of the Harmstons, the jungle is a panacea for his psychological ailments—the “trembling in his body” and the “anxiety that closed in around him.” Less than two weeks after his arrival, he exclaims with giddy confidence: “I feel full of activity and laughter… I think it’s this environment. It seems to send something tickling in me” (p. 132).

For Reverend Harmston, the jungle is the means by which he hopes to realise his utopian vision—a self-contained society on the river. The isolation of Berkelhoost, accessible only by river, lends itself to this experiment. The characters within this domain are acted upon, even “attacked,” by the jungle. Reverend Harmston refers to the environment as “psychic phenomena which tend to stimulate our imagination to unorthodox behaviour,” a place teeming with “passionate, cruel spirits.”

.jpg)