“Public service is about people, not prestige.”

- from the canefields of Albion to the corridors of Geneva, Guyana’s veteran public servant reflects on a life defined by compassion, discipline, and the pursuit of fairness

IN a quiet but decisive tone, Dr Leslie Ramsammy recalls how the ink-stained pages of colonial-era newspapers first stirred his imagination as a boy growing up on the Albion sugar estate.

Long before he became one of Guyana’s most influential public servants and global health advocates, Ramsammy wanted to be a journalist, a voice for fairness and truth in a world that, to him, seemed deeply unequal.

“I grew up during what I would call the glory days of journalism,” he said reflectively. “The newspapers were political, the journalists were fearless, and the stories shaped how people saw themselves.”

He remembers reading the works of Guyanese writers like Ricky Singh and Carl Blackman, men who used words as instruments of resistance. “I wanted to write like them,” he admits. “I wanted to tell stories that mattered.”

FORMATIVE YEARS IN THE SHADOW OF INEQUALITY

Born in Berbice, Ramsammy’s early life was defined by both hardship and aspiration. His childhood on the sugar estates exposed him to the stark divide between the wealthy white managers and the poor workers who kept the industry alive.

“We saw poverty in its rawest form,” he recalls. “Poverty didn’t mean not having a phone or a car, it meant wondering whether you would eat that day.”

He remembers walking past the fenced compounds of the estate managers, watching their families play tennis on well-kept courts while children like him fashioned cricket bats from bits of wood.

“All I wanted,” he said softly, “was to hold a racket, something as simple as that felt like a world away.”

These early encounters with social inequality became the bedrock of his political and humanitarian philosophy.

Even as a child, he questioned why childbirth was so often fatal for poor women and why children in rural villages died so easily.

“If God created life, why are people dying from giving birth?” he recalled asking himself as a boy.

That early moral curiosity would later evolve into a lifelong mission: to make quality healthcare and education accessible to all, regardless of where they were born.

FROM SCIENCE TO SERVICE

Dr. Ramsammy’s academic path led him far from Albion’s dusty roads. He earned a Bachelor’s degree in Microbiology from Pace University, followed by a Master’s and Ph.D. in Biology and Biochemistry from St. John’s University in New York.

He would later serve as a professor of medicine and a senior scientist in the United States before returning home to dedicate his career to public service.

“I came back because, while my work abroad brought satisfaction, it didn’t bring happiness,” he explained. “I wanted to serve my people.”

That decision would define the next four decades of his life. From teacher and scientist to policymaker and minister, Ramsammy became one of the longest-serving public figures in modern Guyana, his career spanning education, health, agriculture, and now diplomacy.

CHAMPION OF HEALTH EQUITY

When he took up the post of Minister of Health in 2001, Guyana’s public health system was struggling with limited infrastructure, scarce resources, and high maternal and infant mortality rates.

“We didn’t have enough specialists, we didn’t have the technology, and many rural clinics lacked even basic equipment,” he recalled.

Under his leadership, Guyana saw dramatic improvements in HIV/AIDS prevention, immunisation, and maternal care.

He spearheaded programmes to reduce mother-to-child transmission of HIV, expanded community health outreach, and laid the foundation for the modern public health infrastructure now serving the nation.

Later, as Minister of Agriculture (2011–2015), he turned the same results-driven focus to rural livelihoods and food security, overseeing modernisation efforts in the sugar and rice industries.

Even after leaving ministerial office, Ramsammy continued to shape policy as an adviser to the Ministry of Health and chair of the Georgetown Public Hospital Corporation Board.

His ongoing work includes leading Guyana’s delegation as Permanent Representative to the United Nations Office in Geneva and as Ambassador to the Swiss Confederation and the World Trade Organization.

Yet despite these global appointments, he insists that his motivations remain deeply personal.

“From the time I was a boy, I believed that where you are born should not determine your chance to live a full, healthy life,” he said. “A child in Black Bush Polder or Moruca should have the same chance of surviving to age five as one born in Boston or London.”

PUBLIC SERVICE AS A CALLING

Throughout his conversation, Ramsammy returned repeatedly to a single theme: service. For him, public office has never been a path to wealth or prestige but a moral obligation.

“Public service should never be seen as a vehicle to accumulate wealth,” he says firmly. “It is about serving your brothers and sisters, whether you are a teacher, a doctor, or a cleaner. You do it because you care about people.”

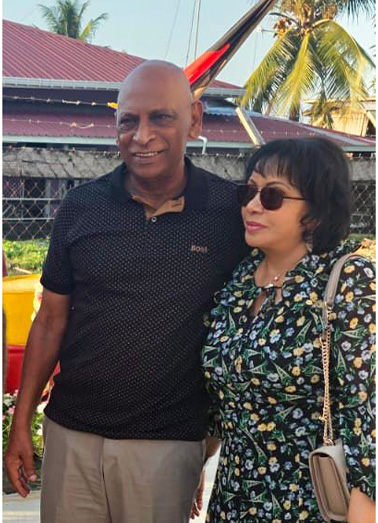

He acknowledges the pressures that come with decades of public life, long hours, constant travel, and separation from family.

“I’ve been lucky to have a supportive family,” he noted. Married for over fifty years, he and his wife raised three children — all born in New York — and are now grandparents.

“Our family life isn’t typical,” he admitted. “We’re often apart, but we stay emotionally close. I made sacrifices, but I also taught my children that true happiness comes from helping others.”

His reflections reveal a man who views success not through material gain but through impact.

“I’ve helped people become wealthy,” he said with a quiet smile. “But I’ve never felt the need to accumulate for myself. My satisfaction comes from seeing others do well, from knowing that someone’s life is better because of something I helped make possible.”

MENTORSHIP, LEADERSHIP, AND LEGACY

Dr. Ramsammy’s influence extends far beyond his formal titles. As a teacher, minister, and diplomat, he has mentored generations of students, civil servants, and health professionals.

“I’ve never failed a student,” he says, recalling his early teaching days. “If someone didn’t pass, I would make them study again, come back, and take the test until they did. My job was to help them learn, not to punish them.”

That same philosophy, he said, guides his approach to leadership. “People make mistakes. But I believe most people are good. They just need guidance, patience, and opportunity.”

Asked what advice he would give to young Guyanese entering public service, Ramsammy paused before answering: “Do your job to the best of your ability, whatever that job is. If you’re a clerk, help someone fill out a form. If you’re a doctor, make sure your patient leaves with hope. Every act of service, no matter how small, contributes to the nation.”

He believes that Guyana’s progress depends on a culture of compassion and collective responsibility.

“We can all change the world,” he said. “Not everyone will build a bridge or write a law, but even small acts, a teacher staying late with a student, a nurse comforting a patient, make the world a better place.”

Even as he represents Guyana on the world stage, Ramsammy remains deeply aware of the country’s unfinished work.

“We’ve made progress,” he said, reflecting on the transformation of the health sector. “We have modern hospitals, trained specialists, and better infrastructure. But our biggest challenge now is motivation, inspiring people to always aim higher.”

He draws inspiration from Guyana’s founding leaders, particularly Dr. Cheddi Jagan and Janet Jagan, whom he credits as moral compasses in his own political journey.

“Janet was one of my early inspirations,” he said. “She fought for the rights of informal workers, for women, for the poor. She taught me that equality is not charity, it is justice.”

Looking back, Ramsammy remains proud of how far Guyana has come, yet he refuses to be complacent.

“We must never allow the pursuit of perfection to become an excuse for paralysis,” he cautioned. “We didn’t always have the resources, but we still built schools, hospitals, and universities because our people needed them. That’s the spirit that must continue.”

A PHILOSOPHY OF HUMANITY

Now in his later years, Dr. Ramsammy continues to serve, not out of obligation, but conviction.

“I will serve to the last breath I take,” he said simply. His life, from the cane fields of Albion to the corridors of Geneva, reflects a single enduring belief: that human dignity should never be determined by wealth, geography, or privilege.

Each night, he said, he reflects on two questions before sleep: “Did I do something today that I am proud of? And did I do something I should not be proud of?”

It is, perhaps, the measure of a man who has spent his life in service, a public servant whose vision for equality was forged not in the halls of power, but in the quiet conviction of a child reading a newspaper on a sugar estate.

.jpg)