ALL across Guyana changes are happening – with development in areas like infrastructure being the most prominent. But in communities like Orealla, more subtle changes are happening, such as better awareness and education. Orealla is one of several Amerindian communities that are determined to develop their people in this way.

Most recently, the riverine community of Orealla has been leading the way in this, with a number of interesting and captivating ideas. The community has begun boat building, a necessary but rare skill implemented by the Board of Industrial Training, with instructors from the community taking the local lead. This initiative marks a significant step forward in preserving traditional skills while adapting to modern needs.

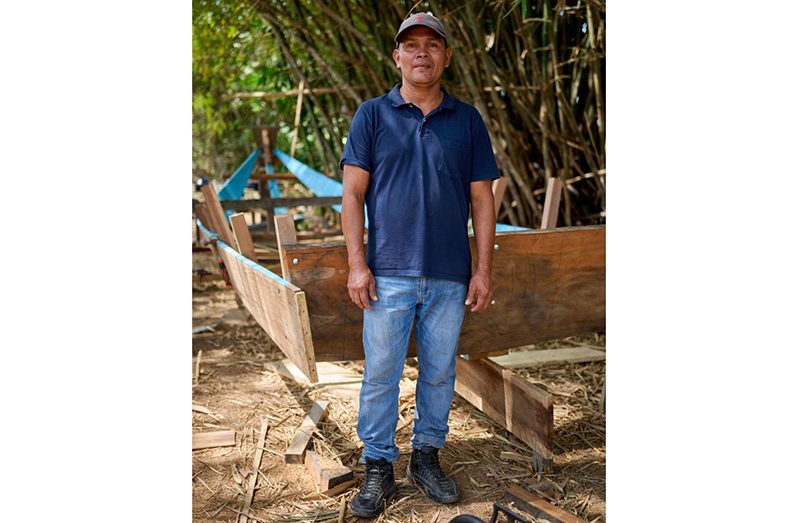

Mitchell Rogers has been a boat builder for as long as he’s been a villager of Orealla—his entire life. He learned the basics of boat building from his father, who taught him the art of canoe carving. Now, years later and with decades of experience, Mitchell is leading a team of young men in learning a dying skill. “I never expected my students would learn so quickly.

I really appreciate how they cooperate and handle things. I often only have to show them something once or twice before they understand the entire process,” he said. “When I was asked if I would be the instructor for boat building, I thought, ‘Wow, can I really do this?’ I had never taught anyone before, but I enjoy the process now. Working with my students and watching them learn has been very rewarding.”

Although the boat-building business may be alive and lucrative, traditional boat-building practices are fading. “My father used to make canoes, but that skill is fading in our community. We don’t have canoes in our village anymore.

I’d love to pass on what I know about building canoes, especially since they’re more durable than boats. A canoe lasts for years, whereas a boat, with constant beating from the waves, wears out faster,” he explained.

Mitchell further added, “With boats, we now have modern tools: planes, sanding machines, and drills, which make the process easier. It’s why people are more inclined to build boats than canoes nowadays.” The shift from traditional canoe-making to modern boat building reflects the broader changes in Amerindian communities as they balance cultural preservation with contemporary needs.

A new generation of builders

For thirty-two-year-old Tyrell Pablo, the programme represents more than just learning a trade. “I never knew how to build a boat, but now I see that this programme is very important for me and others. Everyone is gaining knowledge and ideas on boat building,” he explained. As a fisherman, Pablo sees the practical benefits of these skills. “I chose this course because I am a fisherman, and in the future, I want to build my own boat. It’s very expensive to pay for one,” he said. His concern about preserving these skills is also evident: “If we don’t do something, we will forget what we learned.” The enthusiasm shown by young participants like Pablo demonstrates the community’s commitment to maintaining their connection to the river, which has always been central to their way of life.

Beyond building: creating sustainable futures

The programme’s impact extends beyond just boat construction. Thirty-four-year-old father, Roderick Herman, sees it as a stepping stone to professional development. “I’m a boat captain, and I’m learning to build a boat from scratch, which adds to my trade. This training is helping me learn things I never knew before,” he shared. The programme also ensures that its graduates are certified, something Roderick is happy about. “Most of us don’t have a licence, and after this training, we’ll be able to acquire one.

It’s not just about building the boat but also about learning the rules and regulations of the river,” he said. For Roderick, the benefits are deeply personal: “This will help me take better care of my family once I apply what I learned from this training,” he explained. His perspective highlights how the programme is helping to formalise traditional skills within modern regulatory frameworks.

Fifty-four-year-old Jacob Jack represents an older generation embracing new opportunities. “I’m really happy for this training. Many times, I wanted to build a boat but lacked the experience,” he said. Jacob appreciates the accessibility of the programme. “Things are hard here; at times, you have to pay a trainer to teach you. I’m thankful to the government; we never had training like this before.” Like many others, he sees the programme as a bridge between generations: “I have children, and I want to train them to build something.”

While modern methods may have replaced traditional canoe carving, the spirit of craftsmanship, knowledge-sharing, and appreciation for tradition remain intact. As these skills pass from one generation to the next, they carry with them technical expertise and the cultural heritage of a people determined to navigate their own course into the future.

.jpg)