AS Guyanese, we often hear stories of our national heroes, courageous strong men and women who fought so that we could today celebrate Guyana as an independent nation. Names like Cuffy, Damon, Dr Cheddi Jagan, Linden Forbes Burnham, Janet Jagan, Desmond Hoyte, Stephen Campbell and many others, immediately come to mind.

Guyana’s road to Independence predated the signing of that agreement on May 26, 1966 and runs back all the way to slavery and to the Enmore Martyrs. This article looks at some of the earlier heroes and the architects of the country’s Independence

OVERTHROWING MAGDALENEBURG, THE CUFFY STORY

In the year 1633, the first set of African slaves were stolen from the land of their birth and brought to the new world as slaves, being stripped of their culture, names and identities. By the 1760s there were about 15,000 slaves in the three colonies of Essequibo, Demerara and Berbice.

Longing for their freedom, slaves often attempted to run away or leave their plantations but were in most cases unsuccessful and were flogged or even killed for their plans to leave the plantations due to the inhumane treatment they would have received.

The 1763 revolutions are recorded as a pivotal juncture in the abolition of slavery in not just here but also in the Caribbean. Cuffy, Damon and Quamina, three ex slaves have been greatly credited for their work as the movers and the shakers of the slavery abolition movement.

Following the successful rebellion of slaves who fled into the woods and became “bush negroes’ or Djuka people in neighbouring Suriname, African slaves in Berbice became emboldened to fight for their freedom and decided to undertake similar actions.

Led by a house slave named Cuffy (or Kofi), the Berbice slaves overran plantation Magdaleneburg, removing the colonial masters, and taking their freedom. During this battle for freedom, Cuffy did not act alone; he was aided by two slaves Atta and Akara who served as his right-hand men during this period.

Cuffy and his lieutenants led 3,833 enslaved Africans to their freedom. Cuffy had planned the revolt just as two shiploads of people from Africa had arrived at the docks, which significantly increased the number of Africans in the fight to overthrow the 346 colonial masters.

The rebellion spread like a forest fire to neighbouring plantations, and within one-month, Africans were in full command of most of the plantations in Berbice. Cuffy declared slaves free and the Africans managed the plantations for almost a year.

After the plantations were recaptured by the Dutch, Cuffy shot himself in the head, in a bit to never submit to his enslavers.

Although their freedom did not last due to Dutch reinforcements arriving by ships with heavy machinery to recapture the slaves, Cuffy left a lasting legacy, one that inspired other slaves to fight for their freedom and to never give up until they were free.

The February 23, 1763 Cuffy-led revolution was recorded, in European history, as the first major revolution by Africans in the western hemisphere, and influenced several other revolutions in the west, including the Haitian revolution led by Toussaint Louverture.

DAMON AND THE FALL OF LA BELLE ALLIANCE

Following years of attempts to be free and treated humanely, African slaves gained Independence on August 1, 1834. When the Emancipation Act was finally passed in 1833, it did not automatically give the slaves their freedom. The now freed slaves were transitioned into a period of apprenticeship and continued to work with their former masters for miniscule wages.

This did not sit well with the ex-slaves who had a different vision for what life would be like after freedom. True freedom came in 1838 when the apprenticeship system was abolished.

What started the fall of La Belle Alliance was a problematic move by the owner of Richmond sugar plantation, Charles Bean, who stirred up trouble by killing the pigs and cutting down the fruit trees of the former slaves, which was a subsistence income for those ex-slaves. His excuse for this destruction of the ex-slaves’ properties was that their pigs were destroying the roots of his young canes.

Being displeased with this type of unjust treatment, the ex-slave Damon called on other ex-slaves to oppose Bean. Some 700 apprentices downed tools in aid of Damon’s cause. On August 3, 1838, they protested the apprenticeship scheme. The following morning, the freed slaves were more than surprised, and became angry when they were ordered by their former masters to return to work. By August 9, the labour situation worsened when ex-slaves from Richmond to Devonshire Castle downed tools and gathered in the Trinity Churchyard at La Belle Alliance.

Governor Smyth addressed the workers at Plantation Richmond, telling them that the apprenticeship period was still in force and they should go back to work. He arrested the leaders of the peaceful demonstration. Damon was referred to as the “Captain” and ringleader of the unrest; and at noon on October 13, 1834, he was hanged for rebellion in front of the Parliament Buildings. Although Damon lost his life, his resilience influenced many other ex-slaves and even warned plantation owners of the strength and the will of the Africans to be free.

THE ENMORE MARTYRS

On June 16, 1948, shock waves were sent across Guyana as five sugar workers were shot and killed by police at the Enmore Estate, East Coast Demerara. Lallabaggie and Dookie from Enmore, and Rambarran, Harry and Pooran from Enterprise/Non Pareil, are known as the Enmore Martyrs, who lost their lives while protesting unfair treatment on the sugar estates.

Cane cutters, backed by the Guyana Industrial Workers Union (GIWU), went on strike demanding the abolishment of the existing “cut and load” system in the fields, which was introduced in 1945. Cane cutters had to load the sugar punts with the cane they cut. As part of the demands of the 1948 strike, the cane cutters called for the replacement of “cut and load” with a “cut and drop” system by which the cane cutters should cut the cane, but other workers would load the cut cane into the punts for shipment to the factory.

In addition to this particular issue, the workers demanded higher wages and improved living conditions on the sugar estates. However, the real aim of the strike was to demand recognition of the GIWU as the bargaining union for the field and factory workers on all the sugar estates in the country.

On June 16, a crowd of about 400 workers protested outside the Enmore factory. The management of Enmore Estate expecting this protest action had the evening before requested assistance from the police.

Lance Corporal James and six policemen, each armed with a rifle and six rounds of ammunition were sent from Georgetown on the morning of June 16. At 6:00 hrs, they took up positions in the factory compound which was protected by a fence 15 feet high with rows of barbed wire running along the outward struts at the top.

By 10.00 hrs, the crowd had grown to between 500 and 600 persons and was led by one of the workers carrying a red flag. They attempted to enter the factory compound through the gates and through two trench gaps at the rear by which punts entered the factory. But they were prevented from doing so because the locked gates and the punt gaps were protected by policemen.

Accounts of the incident indicate that one section of the crowd hurled sticks and bricks at the police and a few persons got into the compound from behind the factory. The police tried to keep the crowd at bay but their efforts proved futile. As such, they opened fire which resulted in the death of five sugar workers and injuries to 14 of them.

The sacrifice of those five sugar workers brought enough attention to the plight of the sugar workers that some of the major objectives were achieved, including better treatment of sugar workers. Additionally, the tragedy and the ultimate sacrifice of these sugar workers greatly influenced Dr. Jagan’s political philosophy and outlook.

STEPHEN CAMPBELL

On December 26, 1897, in Santa Rosa, Moruca, British Guiana, Maria Dos Santos and her husband, Tiburtio Campbell welcomed their baby boy, Stephen Esterban Campbell, who, little did they know, would one day become a legend and hero for many Amerindians and Guyanese.

Campbell, who, belonged to the Arawak Tribe, was raised by his grandmother after his parents died.

He was described as a man who never limited his abilities to naysayers, which led him to become the first Indigenous member of the British Guiana Legislative Council that is now called Parliament. He entered the Council on September 10, 1957; hence, September was chosen to honour the national contribution of Indigenous Guyanese.

Campbell was the holder of many professional caps. He was a teacher at various villages and settlements, he worked in bauxite mines and he did farming. His work with common labourers and the difficulties he endured, certainly shaped his views and influenced his activism for education for Indigenous peoples.

Campbell was at the age of 60 when he entered party politics, joining a party called the National Labour Front (NLF). He was particularly passionate in his fight for equal opportunities for Indigenous Peoples during his tenure as a politician.

A strong believer in empowerment and self-sufficiency, Campbell fought vigorously during his parliamentary days for educational opportunities and land rights for indigenous communities.

During the colonial days, the then rulers allowed Amerindians to live their life in ‘reservations’, according to their traditions and practices, subject to certain limitations.

However, Amerindians at that time had no formal title of ownership or established legal rights to the lands which they used or where they lived, which saw fear arising when there were talks of then British Guiana becoming an independent country.

The people feared that after the country gained Independence, whatever rights they enjoyed would have been trampled upon and ignored and the lands on which they lived and built their families on for thousands of years would have been expropriated.

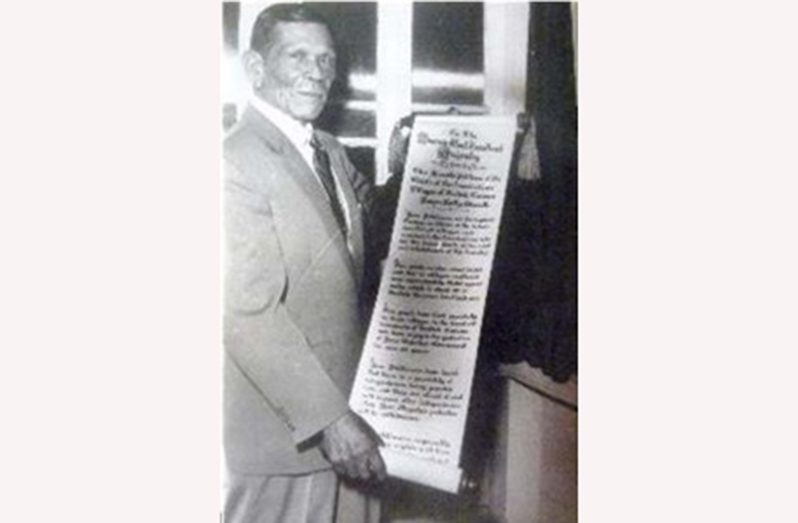

In 1962, Campbell travelled to London to present a petition and lobby the British Government for recognition of Amerindian land rights. On that first visit to London, Campbell took with him a petition which was written on a long scroll and signed by dozens of Indigenous leaders of the day. He presented it to the British Secretary of State, Duncan Sandys, in London, after having a private, one-hour meeting with him.

Sadly on May 12, 1966, two weeks before British Guiana gained Independence, Campbell passed away while he was receiving treatment in Canada where he was later laid to rest.

However, the works that he did during his last days made sure that when Guyana attained its Independence on May 26 1966, Indigenous Peoples had legal ownership of land and rights of occupancy and these were embodied in the Independence provisions.

GOVERNMENT OF UNITY: THE CHEDDI, BURNHAM STORY

Dr Cheddi Jagan and Linden Forbes Sampson Burnham ushered in a period of togetherness for Guyanese just prior to the country gaining its independence from its colonial masters. Being ruled by the first Government of unity was great for the Guyanese people who were seeking to recreate their country, freeing it from its colonial past and preparing it for a brighter future.

Dr Jagan, Guyana’s first Premier, was born at Port Mourant, a sugar plantation on the Corentyne Coast of Berbice, on March 22, 1918. His parents came to British Guiana from India as indentured labourers. Jagan’s father was a cane cutter, who became a field supervisor for cane cutters. Jagan received his high school education from Queen’s College, an exclusive secondary school in Georgetown that was reserved for children of the middle class. Upon graduation from high school, Jagan migrated to the USA and studied pre-dentistry at Howard University for two years. He completed his education as a dentist at Northwestern University.

Linden Forbes Sampson Burnham was the son of a schoolmaster. He also attended Queen’s College. Renowned for his scholastic ability, young Burnham won the Guyana scholarship, which earned him the right to free university education in the UK.

Burnham studied at the University of London. He was subsequently admitted to the bar as a barrister-at-law at Gray’s Inn.

When Burnham returned to British Guyana in 1949, Jagan was already well known as an anti-imperialist fighter for the working class. Dr Jagan was one of the first leaders of the Caribbean to call for independence from British colonialism. Burnham and Jagan teamed up under the political banner of the PPP, forming an alliance that became a formidable political force.

Burnham became deputy leader of the PPP, Jagan was elected leader. Together, these energetic young men made the PPP a vibrant political force. They were at the forefront of a new political movement that swept through the rural countryside, through villages, sugarcane plantations, and rice fields of the country; ordinary citizens participated in politics.

The PPP won the national elections in 1953 and Dr Jagan became premier, head of the Cabinet; Burnham was named Minister of Education, and other young African and East Indian men and women also enjoyed their first experience at party politics serving as Members of Parliament and also in several ministerial post.

This was the first Government of unity of Guyana: East Indians and Africans came together under the leadership of Dr Cheddi Jagan. He sought justice for his constituents, regardless of their race.

This type of cohesion did not sit well with the colonials who sought to see Guyana divided one race against another, and shortly after British troops invaded Guyana. October 1953, in an effort to revert all that was done by the Indo and Afro Guyanese leaders, Jagan and Burnham, the British invasion begun. The soldiers came with orders to terrorise the people and to shoot if necessary. The troops terrorised people into disavowing any affinity with the PPP. In the midst of the invasion, Dr Jagan and several members of his Cabinet were thrown in jail on trumped up charges of sedition and treason, for allegedly abusing the Queen. The governor took full charge of the Government and assumed absolute powers. By declaring a state of emergency, the Governor usurped the roles of Parliament, the Prime Minister, the Cabinet, the Judiciary, and the commanding officer of the armed forces, all with the complicity and backing of his compatriots in the British Parliament.

So, after a bold bid for self-rule, British Guiana was back in the clutches of British imperialism. Once again the local whites regained the control over the affairs of the colony that they had surrendered just a few short months earlier. This British rule by force lasted four years, while the people’s elected representatives were either incarcerated or were busy defending themselves against trumped-up charges. PPP political leaders had to raise several thousand dollars to hire senior British lawyers to defend them in court. Of the detainees, Dr Cheddi Jagan, Janet Jagan, Sydney King and other former members of the PPP Government remained captive but later won their case and were released to continue leading Guyana forward as the country stepped into a new age.

(This piece was compiled from stories in the Guyana Chronicle archives)

.jpg)