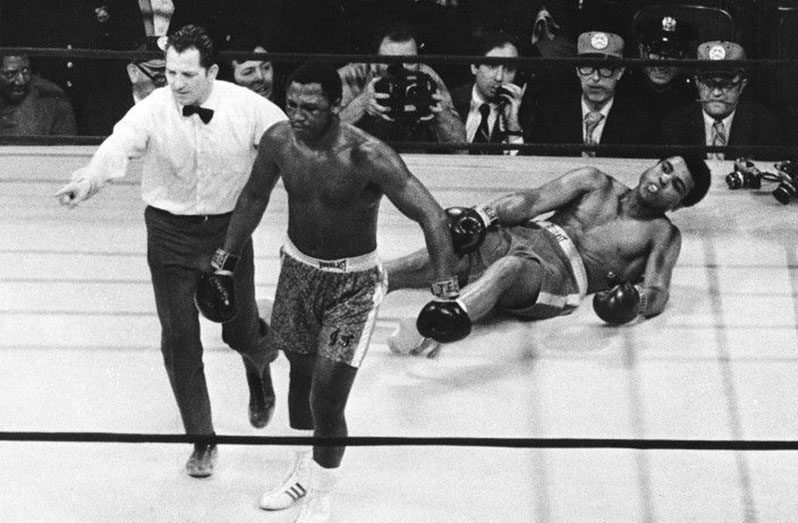

ITS global appeal was so wide that it was billed as simply: ‘The Fight’. Yet 50 years on from the first of the Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier mega-bouts, details from the two icons’ bitter dispute continue to compel generations of fans.

The vast scale of their undisputed heavyweight title fight on March 8, 1971, which Frazier won by unanimous decision, remains one of the most important moments in boxing history.

When Anthony Joshua and Tyson Fury get their £100 million payday, they will have ‘The Fight’ to thank. Both undefeated and in their prime, Ali and Frazier were the sporting giants of their day. With the purse of an unheard of $5m, being heavyweight champion of the world really was the richest prize in sport.

But the untold story which forms the backdrop for the bitter dispute between the two icons – more so on the part of Frazier – is a much more complex affair. Fans would pick a side based on their views on the Vietnam War while the relationship between the two titans would never recover.

Jerry Izenberg, now 90, and then a sports reporter in New York, takes up the story. “It’s kind of an amazing thing. There was a lot of tension which I really didn’t understand until much later,” he told Telegraph Sport.

Ali, returning from a three-year ban for failing to sign up for the Vietnam War draft, was 26-0 with 23 knockouts, Frazier was 31-0, with 25 knockouts. Frazier held all the belts; Ali was considered by The Ring magazine as the No 1 in the division.

Their first meeting was played out to a backdrop of extreme political and civil unrest which can be hard to comprehend even now. Frazier had actively helped out Ali while he was banned from fighting for three years because he had refused to sign up for the Vietnam War draft.

On April 28, 1967, with the United States at war in Vietnam, Ali refused to be inducted into the armed forces, saying: “I ain’t got no quarrel with those

Their first meeting was played out to a backdrop of extreme political and civil unrest which can be hard to comprehend even now. Frazier had actively helped out Ali while he was banned from fighting for three years because he had refused to sign up for the Vietnam War draft.

On April 28, 1967, with the United States at war in Vietnam, Ali refused to be inducted into the armed forces, saying: “I ain’t got no quarrel with those Vietcong”. Two months later, Ali was convicted of draft evasion, sentenced to five years in prison, fined $10,000 and suspended from boxing.

The prison sentence was dropped on appeal, and Ali returned to the ring on October 26, 1970, knocking out Jerry Quarry in Atlanta in the third round. Then the fight with Frazier was made.

“Joe had loaned Ali money when he was out of work,” Izenberg continues. “Joe had even gone back to the commission and asked if they would give him back his licence. They were afraid he was going to jail. [The promoters] wanted to get the fight in before he went to jail, it was a matter of money for everybody but Frazier.

“In the build-up, when Ali went to Joe’s gym, to taunt him with ‘come out sucker, we’ll settle it right here’, it angered Joe terribly. You didn’t do that with Joe. He headed for the door and Ali before his manager said: ‘You ain’t going anywhere. The fight of the century ain’t going to happen on a side street.’

“It got to be very tetchy and after the third fight [in Manila] with the gorilla thing (Ali taunting Frazier), they never made up. I don’t care what people say, they never made up.”

Away from the record purse and the glamour of the fight, Izenberg paints a picture of a “horrible” era with America on the edge. It came to define the fight and it is shocking to hear even now, half a century on.

“You’ve got to understand America at that time,” he recalls. “I wish I could forget it but I’ve got to remember it. It was totally divided. It was the worst I’d seen it divided since pre World War II when the Klan were here.

“I learned about anti-Semitism when I was seven. We were divided on everything. We were divided on Vietnam. Before that fight, hippies and hard hats were fighting in Times Square of all places with pipes and baseball bats. It was horrible.”

“People then decided their choice of which fighter they would root for was based on the war. Ali had no quarry with the Vietcong so 60 per cent or so were rooting for Ali. The other 40 per cent were rooting for Frazier. That night in the arena I would say 70 per cent was pro-Ali because they were New Yorkers and they had the money and they went to the fight. The fight itself was fantastic because of the emotion and because of the crowd.”

Getting a seat at the event was like a golden ticket. The actor Burt Lancaster was ringside as part of the commentary team, Frank Sinatra was a credentialed photographer for Life Magazine, working on the ring apron. Cinemas in New York showed the fight and even sold seats behind the screen, with fans prepared to watch the fight in reverse, Ali and Frazier fighting as southpaws.

The only fight which came close to gripping the planet before ‘The Fight’ was the 1938 rematch between Joe Louis and Max Schmeling – with the backdrop of the rising heated political conflict between Nazi Germany and the United States. It serves to show how the biggest nights in boxing are often defined by the wider cultural mood music.

The German regime were exploiting Schmeling’s success in boxing in its propaganda efforts through minister Joseph Goebbels, and although the boxer had refused the ‘Dagger of Honor’ award offered by Adolf Hitler, within his entourage there was an official Nazi Party publicist, who had issued statements that a black man such as African-American Louis could not defeat Schmeling.

There was even a quote from the publicist that Schmeling’s purse from the fight would be used to build more German tanks. A few weeks before the rematch, Louis had visited President Franklin Roosevelt at the White House. The New York Times quoted Roosevelt as telling the fighter: “Joe, we need muscles like yours to beat Germany.” Louis, of course, went on to knock Schmeling out in the first round.

These fights charted a path towards Fury v Joshua, most likely headed to one of the Middle East countries, with its own political overtones, and with the protagonists set to earn up to £100m pounds each, according to the promoter Eddie Hearn.

So what does Izenberg make of it? “‘The Fight’ dwarfs it,” he says, “it absolutely dwarfs it because of the emotions involved. It doesn’t resonate the way Frazier-Ali did. In terms of Great Britain it’s probably a bit bigger because emotions are aroused for different reasons. But few fights will ever match that night in New York, and the build up to it.”

(The Telegraph)

.jpg)