By Ravena Gildharie

FROM well-planned thoroughfares, Georgetown once boasted the most picturesque timber architecture; a City with prolific concepts and styles from foundation to the roofs of almost each building, and distinctive of its architect. Much detail even went into the design and construction of surrounding fences and railings of stairways and bridges.

Today, we are witnessing this iconic characteristic evolving into a bustle of concrete, steel and glass fabrications that leave much to be desired in terms of architectural talent that can impress future generations the way Cesar Castellani, John Bradshaw Sharples, Joseph Hadfield and others from the 18th and 19th centuries did. The works of these men live on today in charming historical remnants such as the Public Buildings, Victoria Law Courts, Georgetown Magistrates’ Court, Walter Roth Museum, Moray House, St. George’s Cathedral, Red House, City Hall, St Andrew’s Kirk and others, as well as a few private residences, particularly in Queenstown and Kingston.

Undeniably though, Georgetown’s famed wooden architecture continues to fade; much of it having been destroyed by fire and others being pulled down without haste, as part of the City’s growing commercialisation and contest for ideal business spots. While this is happening unnoticed by many, there are a few persons who are saddened by the apparent lack of inspiration and consideration for architectural designs and constructions of both public and privately-owned structures.

Retired Civil Engineer Egbert Carter, age 74, grew up in Georgetown from about age seven years and has been very impressed by, not only the engineering aptitude but the artistic skill and details, captured in some of the largest and most-admired wooden structures erected in the city, dating back to colonial times. He described Georgetown as “a beautiful city with fascinating architecture details that were out of this world.”

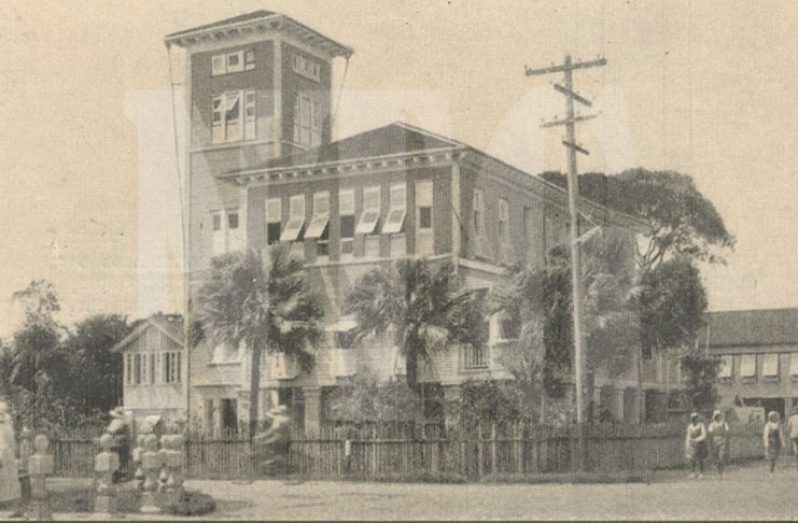

However, in his view, the St. Stanislaus College on Brickdam, built in 1926 and designed by John V. Mittelholzer, a Guyanese architect of British Guiana, marked the end of Georgetown’s prominent and prolific architectural heritage.

“It was mostly a Victorian-style architecture punctuated by local and modern styles but Sharples, Castellani and Mittelholzer kept function and form relevant,” Carter said during an interview with the Pepperpot Magazine at his East Bank Demerara home, where he shared an elaborate pictorial and detailed-research presentation on ‘Old Georgetown – from the late 18th century to early 19th century.’

One of Guyana’s most reputable engineers, who also sits on the Central Housing and Planning Authority (CPHA) Board, Carter believes that the construction of houses and other buildings today is based on a ‘copy-cat’ style, lacking creative ingenuity. This is perhaps due to the client-based demand for cheaper costs and longevity that can be delivered in the quickest time span.

As a historical heritage and cultural activist too, Carter lectures voluntarily at Moray House, guided by his wealth of engineering experience and backed by extensive research.

Reflecting on the age-old architecture, he pointed out that it was evident that “much detail went into planning, architectural design and construction of most of the buildings” situated around Georgetown. Buildings including businesses, were constructed at least two to three feet above ground level with each having a three-step stairway at the entrance. This was a precaution against flooding.

Built predominantly of timber, Carter observed that the homes were designed with peaked roofs that created a relatively cool atmosphere with open bannisters, featuring spindles that allowed breeze to openly enter and circulate in the houses. Bedrooms were particularly situated on the eastern side of the houses, ideal to capitalise on the trade winds while the roofs were covered by mostly Wallaba shingles. Windows were the popular Demerara shutters.

Prominent architects and some wooden marvels

From a façade of highly-pitched roofs and ceilings, wooden latticework and Demerara Shutters, one can distinguish Castellani’s signature styles as he was seemingly very conscious of his environment, which influenced his designs. Born in Malta, Castellani is believed to have immigrated to British Guiana sometime during 1860 with a group of Italian priests. His creativity is noted in the Georgetown Magistrates’ Court, Castellani House on Homestretch Avenue, the vaulted ceiling at the Public Buildings, the Brickdam Police Station and the Palms Geriatric Institution on Brickdam.

Castellani also added his touch to the towers of the previous Sacred Heart Church, destroyed by fire in 2004, and the ceilings at the Public Buildings, another classical feature of Georgetown’s architecture. It was designed and built by Hadfield nestled on a foundation of greenheart logs and limestone, laid in 1829. The structure is described by the National Trust of Guyana as “an excellent example of 19th Century Renaissance

Bloomfield under repairs at present

architecture, stuccoed to resemble stone blocks.” It is one of two doomed buildings that exist in the city and even the original fence boasted ironwork detail support while the gate featured a box column ironwork. Hadfield also designed the St Andrew’s Kirk, said to be Georgetown’s oldest building.

The architect noted mostly for cast iron-work, especially in stairs and balconies, was Sharples, who was born in the colony to a British architect/builder and an ex-slave woman. His design in houses also features steep gable roofs and carved doors. Some of these still standing today, include the Walter Roth Museum on Main Street and Sharples’s House on the corners of Anira and Oronoque Streets, Queenstown. Sharples is mostly recognised for carrying out one of the largest contracts of that time to build all of the railway terminals, bridges, stores and other railway projects from Georgetown to Rosignol.

Other famous wooden marvels include the St George’s Cathedral, currently under repairs; and the City Hall, intended for massive rehabilitation as part of a planned $200 million restoration project. The architectural design of City Hall was done by Father Ignatius Scoles, featuring a Gothic Revival style, built in a rectangular shade in timber with three floors. Prominent features included the towers with wrought-iron correlations and the hammer beam roof.

Similar cast iron designs, particularly in the form of arches, had been noted on bridges that connect South Road and Croal Streets, and along the Avenue of the Republic.

The St George’s Cathedral is another architectural marvel ranked among the tallest wooden buildings in the world. It was designed by British architect, Arthur Bloomfield, with mainly Gothic arches, clustered columns and flying buttresses. It is the fourth St George’s built by the Anglican Church and was opened in 1893.

Currently, the building is under repairs as customary to maintain this massive wooden edifice for future generations.

Shift to concrete, steel and glass

The constant maintenance of timber structures over the years has been responsible for the gradual change in the façade of most of the city’s architectural wonders. This is also one of the factors that are influencing the shift from timber construction to more affordable and stronger modern materials such as concrete, steel and glass.

Marcel Gaskin and Associates Limited is one of the most prominent engineering and architectural design firms operating for 28 years. The firm has designed and supervised construction of some of the largest structural and engineering projects including city businesses like Citizen’s Bank, New Building on Camp and South Road, Marian Academy on Carifesta Avenue, Queenstown Masjid and the reconstructed Sacred Heart Church on Main Street. This firm also designed Giftland Office Max Shopping Mall, the National Public Health Laboratory and the Diamond Service Station and Fast Food Court.

Managing Director, Marcel Gaskin explained to this publication that his designs are based on client demands and mainly features the use of concrete, steel and glass, most of which are imported. This is in stark contrast to previous constructions that predominantly utilised local timber and clay bricks.

However, Gaskin pointed out that the modern materials are more durable and add to the longevity of the structures which can last three to four years without maintenance. The use of aluminum cladding is rapidly gaining popularity as it is available in pre-painted styles and easy to clean with little or no maintenance required over time.

Though inspired by modern designs observed during his travels and from the internet, Gaskin pointed out that there is very little room for architectural creativity given the fixed demands of clients. Very little attention is given to style, rather it is which design can be most economical and faster to build. He, too, noted that properties boasting the most charming wooden architecture are highly priced not due to design, but location and business owners waste no time in pulling it down to erect modern structures.

Globally, modern architecture is based on the evolution of new building technologies and materials that can create stronger, taller and lighter buildings. Modern features include expansive floor to ceiling glass and limited ornament where decorative mouldings and elaborate trim are eliminated or greatly simplified, giving way to a clean aesthetic where materials meet in simple, well-executed joints.

.jpg)