Contribution from Lawrence Lachmansingh, David Singh & Kojo Parris

Saint Stanislaus College alumni Lawrence Lachmansingh, David Singh & Kojo Parris have been exchanging views around their enduringly common interest: Guyana. Having completed a three-part Series titled, Taking the Pulse: Public Trust, Corruption and Violence, they propose a path away from the escape routes of suicide, migration and public disengagement. Guyana is rated as having the highest, or very high, levels of suicide, migration and public disengagement globally.

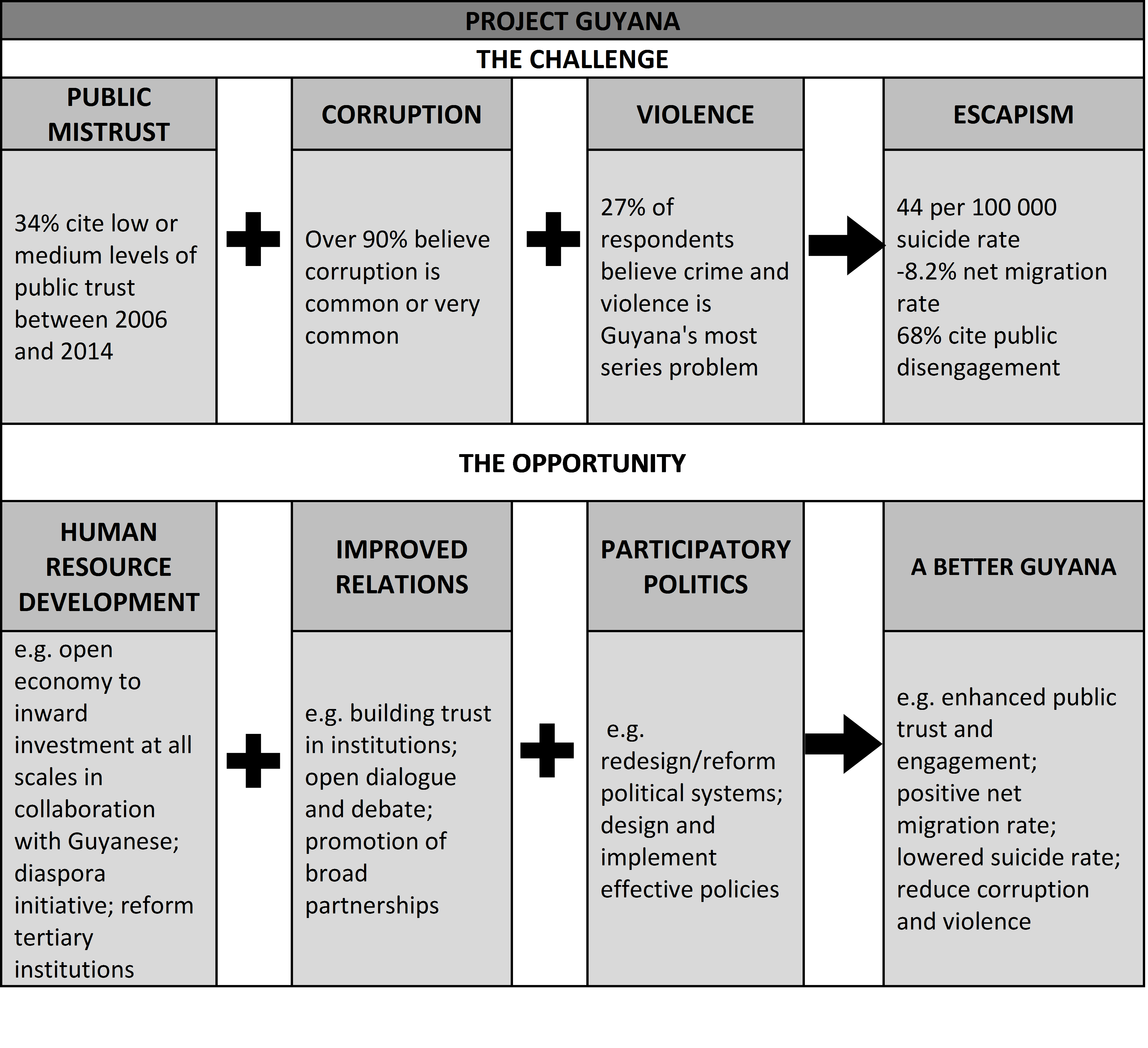

IN this article, we weave three main and overlapping themes that characterise both the challenge and promise that is Guyana in 2015, themes that might well be a basis for an enduring and meaningful “Project Guyana”. We are cognizant that there are numerous approaches taken by people when they consider the future for their societies. We choose an approach drawing from the simplicity in the logic of the late Professor Ali Mazuri, world-known academic and political writer who penned the seminal work: “The Africans: A Triple Heritage” in the 1980s. Our approach is meant to simplify without becoming simplistic.

According to the 2014 LAPOP Survey, rising Public Distrust, Corruption and Violence are all reaching worrying levels in Guyana. The former are not only high in absolute terms but also when compared to other countries within the Americas.

Taken together in Guyana, public distrust, corruption and violence correlate directly with three key “escape” indicators: migration, suicide and apathy. The World Health Organisation (2012) placed Guyana’s suicide rate at 44.2 per 100 000, the International Organisation for Migration (2013) placed migration rates at -8.2%, and an average 68% of LAPOP respondents having never engaged social institutions. These rates are amongst the highest in the world, in spite of the substantial investments in education, and in building social and institutional structures, and in support of the rule of law and governance over the years.

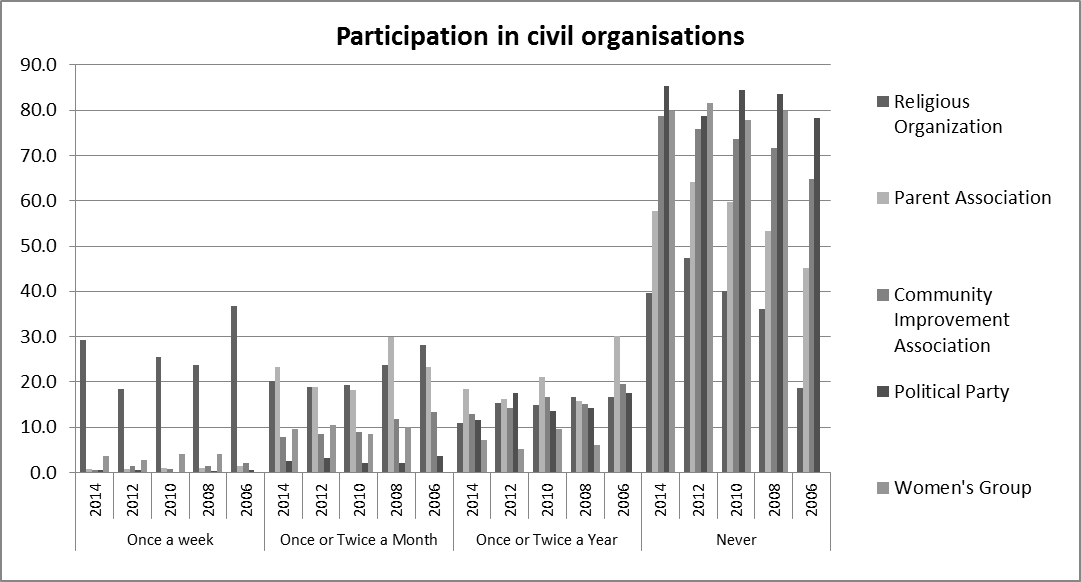

While suicide and migration may be considered to be definitive forms of escapism, levels of public engagement in community groups and organisations may also be a good indicator of “opting-out.” LAPOP statistics on public engagement between 2006 and 2014 show that 65% of respondents cited had never attended social associations such as a parents’ association or community improvement associations. If attendance at religious organisation is excluded, this number climbs to 72%.This form of indifference correlates with a lack of political affiliation, where an aggregate 80% of respondents did not identify with a political party, and an average of 77% indicating that they had little or no interest in politics (Figure 1).

Sustainable development is not possible if migration, suicide and public disengagement are not consensually addressed. Responding to this crisis of confidence in Project Guyana requires numerous actions and tactics that support a few key strategies. These must necessarily be based on a theory of change that addresses as best as possible the complexities inherent in Guyana’s abnormal numbers.

One compelling theory of change suggested by the data is that strengthening participatory political systems that engender social cohesion at all levels will result in improved governance performance, creating the space for people to participate rather than to escape from the challenges of forging a better, stronger and more resilient community in which they live (Figure 2). Clearly there are a number of enabling activities that will have to form part of such a programme, inclusive of implementing and enacting existing and new policies, laws and strategies that involve citizens at a profound level.

One critical strategy within this theory is the need for improved relations across the various divides. An improved way of relating is needed to permit meaningful and healthy dialogue and debate, legitimacy and even consensus on Guyana’s critical and required policy changes. In other words, improved political systems are only partly about the rules of engagement (constitutional reform, electoral reform, governmental reform etc.): it is also about the quality of that engagement.

A second vital strategy suggested by Guyana’s realities is the need to reduce human resource deficits. With such a small population and a high migration rate (particularly of post-secondary graduates), there is not enough human resource capacity available to perform the many important functions at hand. Structured programmes to open the economy to inward investments at all scales in close collaboration with Guyanese, and a vibrant diaspora initiative are certainly areas to be explored. Starting with the University of Guyana and the Training and Teaching Colleges, an educational system that trains Guyanese for Guyana should be hastily designed and implemented.

Conclusion

Professor Mazrui stated that navigating the dynamics of traditional, Euro-Christian and Islamic heritage inform the framework for understanding African society. This ‘Triple Heritage’ at once described the black/African dilemma and mapped an enduring platform for progress presented by this textured heritage. With paradigmatically less scholarship and even profundity, we have highlighted three central spheres of concern in Guyana, and rather less clearly, call attention to some of the macro questions which arise. These three spheres of concern, public trust, corruption and violence, echo the sentiments of the ‘Triple Heritage’ in that they represent both a challenge and an opportunity for Guyanese.

We cannot claim a monopoly on the logic for a healthy and sustainable future for Guyana. At the same time, our society would demand us to address questions such as where should we turn to for leadership, and what are the qualities expected of such leadership? What role should the diaspora play? To what extent do we need to address our minds to the root causes associated with the abnormal numbers, and should this be contained within the actions and tactics rather than a precondition for action? What explains the paradox of high levels of escapism and human capital loss, alongside high levels of sustained growth in GDP and improvement in Human Development (as measured by the UN-HDI) in Guyana over the past many years?

We thank the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) and its major supporters (the United States Agency for International Development, the United Nations Development Programme, the Inter-American Development Bank, and Vanderbilt University) for making the data available.We have worked also with an analyst from Corruption Watch in South Africa, unconnected to our part of the world, to analyse the data.

For those who wish to share their thoughts on these pieces, we may be reached via e-mail at 3Guyanese@gmail.com.

.jpg)