Fostering the return and rise of rare species

LAST week, Pepperpot Magazine highlighted a remarkable venture aimed at conserving the beauty of the Rupununi. This week, we shifted focus to conservation at the community level. Deep within the Rupununi, communities are more attuned to nature than most. These are the communities experiencing the direct impact of conservation efforts, and they are also the driving force behind these initiatives.

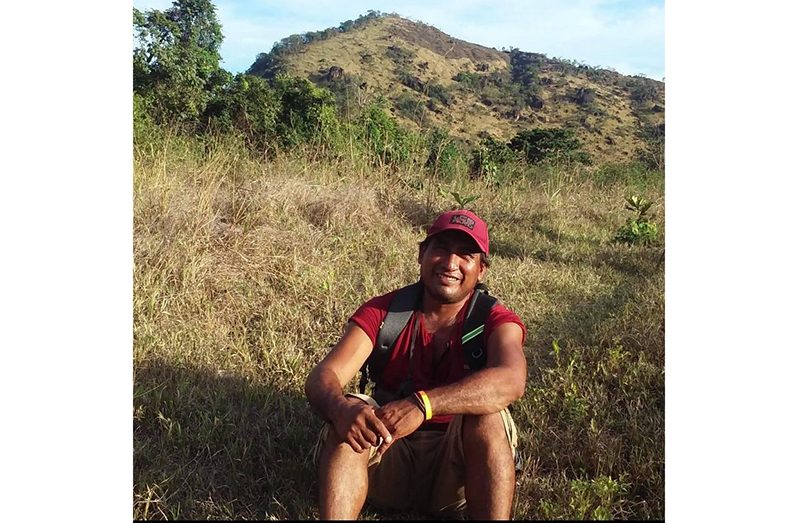

Asaph Williams, born and raised in Katoonarib, witnessed a significant decline in the rare and beautiful species he grew up with. Concerned for the future, Asaph and several community members took steps to protect the natural habitats of the region’s wildlife. Their efforts have already benefitted dozens of communities, and despite the ongoing challenges, Asaph and his team are determined to keep the Rupununi vibrant.

Asaph Williams: A Passion for Conservation

Asaph Williams is one of the founding members of the South Rupununi Conservation Society (SRCS) and currently serves on its executive board. A councillor in the village council of Katoonarib, he possesses a profound passion for wildlife, conservation, and traditional living. Known as a skilled bird guide, he attracts birdwatchers from around the globe who are eager to explore the region with his expertise.

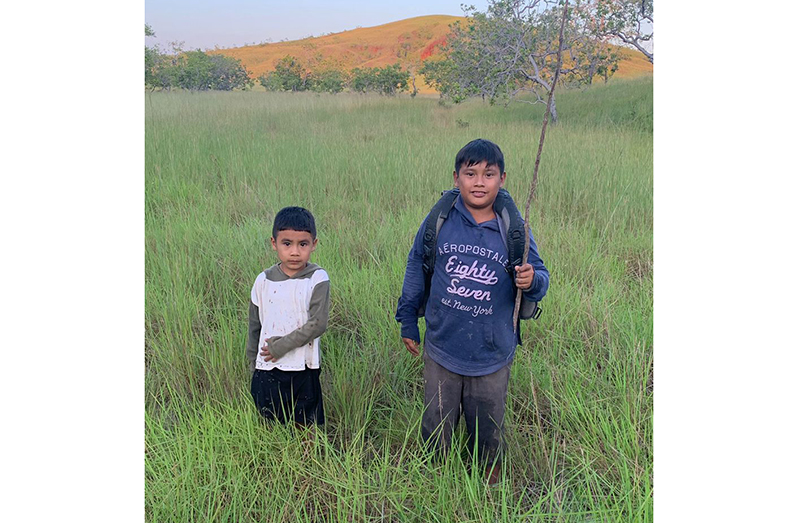

Katoonarib, located in South Central Rupununi, is one of the most captivating communities in the area, aptly described as a “Bush Island.” This unique village is one of the few that features trees amidst the vast openness of the savannah, creating a diverse habitat that supports a richer array of species than its surrounding counterparts. It serves as a vital refuge for wildlife and a crucial resource for farming and hunting.

For years, the people of Katoonarib have fostered a near-symbiotic relationship with their local wildlife. However, Asaph noticed subtle changes over time. As the community grew, misconceptions about the impact of their activities on wildlife and ecosystems began to emerge. “There used to be a lot of wildlife here. People relied on the land because they didn’t have money. But as the population increased and people settled in one place, hunting pressure intensified, and resources became strained,” he explained.

Observing change

Asaph has spent much of his life observing the wildlife in his community, and he has seen changes that many others overlook. Decades of pressure on natural habitats have taken a toll. “I noticed a lot of changes; there is less wildlife now. It’s not as easy to spot animals as before. People need more materials for houses, which is changing the forested areas,” he noted. Climate change compounds these issues, with unpredictable weather patterns affecting both the community and wildlife.

Faced with the decline of the natural beauty of his village, Asaph and his peers took action. “I started SRCS with discussions among friends and family about our concerns for disappearing wildlife. Twenty years ago, it was a dream we discussed over drinks. We began by engaging our family and friends holding meetings and workshops. This is how my community became involved in conservation,” he stated.

Innovative conservation practices

The SRCS employs various innovative practices that blend traditional knowledge with scientific methods to address the challenges posed by declining animal populations and climate change. One of the most surprising tools they use is fire. “We use fire, which is often seen as destructive. However, we also use it as a conservation tool. We burn around our bush islands at specific times to prevent savannah fires from entering and damaging our farms or wildlife,” Asaph explained.

He emphasised the importance of understanding breeding seasons and identifying crucial habitats. “Our traditional knowledge helps us pinpoint these areas, contributing significantly to our conservation efforts,” he added.

The role of tourism

Asaph and the SRCS have managed to balance traditional practices with modern conservation methods. Additionally, tourism has emerged as a critical tool in their conservation efforts. “Balancing modern and traditional life can be challenging, but tourism can play a vital role. The more visitors appreciate what we have, the more they value conservation as a sustainable way to generate income,” he remarked.

Since implementing conservation measures, Asaph has begun to witness positive changes in his village’s wildlife. “My village is starting to see the value of conservation. We are observing species returning—like peccaries and songbirds that had previously disappeared. With government support for savannah farming, we are easing the pressure on the forests,” he explained.

Ongoing Challenges

Despite these successes, Asaph acknowledges that challenges remain. “We live in a cash-driven world. Ironically, the more money people obtain, the more pressure it can put on the environment. Housing projects can encourage neighbouring villages to encroach on our protected bush islands, threatening the habitats we strive to maintain,” he shared.

As the world shifts towards a lifestyle increasingly disconnected from nature, Asaph remains optimistic about the future of the Rupununi. “I see Indigenous peoples respecting wildlife, taking pride in seeing animals thrive. Communities are becoming more active in conservation efforts, zoning areas like Katoonarib’s bush islands to safeguard them as vital refuges,” he said.

Asaph Williams and the South Rupununi Conservation Society exemplify the power of community-driven conservation. By blending traditional knowledge with modern practices, they have created a model that not only protects wildlife but also enhances the livelihoods of local people.

.jpg)