— If not, why not?

HISTORY OF THE UK OIL AND GAS FISCAL REGIME

IT is worthwhile to highlight that the UK’s fiscal regime is designed with a number of built-in incentives. For example, the 25 per cent tax levy or windfall tax includes an additional investment allowance of 80 per cent that can be claimed at the point of investment. Overall, the tax relief companies receive from qualifying expenditure in the UK has nearly doubled from 46p for every £1 to 91p for every £1. Put differently, for every US$1 billion invested in the UK oil and gas industry, the oil companies receive US$912.5 million in tax relief under the new (current) scheme.

IT is worthwhile to highlight that the UK’s fiscal regime is designed with a number of built-in incentives. For example, the 25 per cent tax levy or windfall tax includes an additional investment allowance of 80 per cent that can be claimed at the point of investment. Overall, the tax relief companies receive from qualifying expenditure in the UK has nearly doubled from 46p for every £1 to 91p for every £1. Put differently, for every US$1 billion invested in the UK oil and gas industry, the oil companies receive US$912.5 million in tax relief under the new (current) scheme.

That said, it is normal practice universally for petroleum producing countries to design a separate fiscal regime specifically for the oil and gas industry that is usually different from the mainstream fiscal regime applied to companies operating in other sectors. This is the case in the United Kingdom and in Guyana. Important to note as well is that there are different types of fiscal regimes that can be applied to the oil and gas industry. The reason for this is largely because of the highly capital-intensive nature of the industry, the nature of the project life cycle which spans about 30 years, 10 – 15 years of exploration, another five years developing the fields for production (provided that the fields are commercially viable), and another 10 years of productive life; the volatility of oil prices which is impacted by market conditions (demand and supply) as well as geopolitical tensions, and more so, the high-risk nature of the industry. In the case of Guyana, for example, the projected investment by the co-ventures (EEPGL, Hess and CNOOC) for the Stabroek block is about US$60 billion of which US$29.3 billion have already been committed to develop and produce from four approved projects. The total projected investment (US$60 billion) is 15 times Guyana’s pre-oil GDP of US$4 billion.

OBJECTIVES OF THE OIL AND GAS FISCAL REGIMES

Governments typically design the fiscal regime to support its twin objectives of maximising the economic recovery of hydrocarbon resources whilst ensuring a fair return on those resources for the nation. A ‘fair return’ implies that a share of the profits should be retained for the nation, whilst ensuring returns on the private investment needed to exploit these resources is sufficient to make extraction activity commercially attractive. This is particularly important where ownership of companies by foreign investors means corporate profits flow overseas (HM Treasury, 2014). In practice, the design of oil and gas taxation involves making judgements about the combination of tax measures that will achieve the right balance in achieving these objectives. Key consideration is the degree to which a lower effective tax rate will incentivise investment in more challenging fields to increase production in future. This is important not just in ensuring a future flow of tax receipts but wider economic benefits such as employment, skills, supply chain activity, exports, and security of energy supply. However, these benefits need to be balanced against the risk of incurring deadweight costs – that is, reducing the return for the nation from less economically challenging fields which would have still been commercially attractive at a higher tax rate (HM Treasury, 2014).

Another judgement is the trade-off between a simple regime which is easily understood by investors, but which fails to take account of the commercial challenges of individual fields, and a more tailored regime which seeks to match tax take to the profitability of fields, but at the cost of greater complexity. These judgements change over time as circumstances change.

Some changes in tax policy are a response to changes in the commercial position of the industry, which is driven by fluctuating oil and gas prices, its cost base, and the value of future commercial opportunities. Some tax changes are a response to the wider UK fiscal position, such as the current need to reduce the fiscal deficit. Therefore – in common with other countries – the regime has been adapted over time (HM Treasury, 2014).

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE UK’S FISCAL REGIME

In the interest of a comparative illustration to demonstrate whether the application of a “windfall” tax in Guyana has any merit and justification to so do, as in the UK; this section seeks to demonstrate a practical application of the UK’s fiscal regime inclusive of the windfall tax and compared to Guyana’s current fiscal regime. In so doing, however, it is essential to note that some elements of the fiscal regime in the UK are not comparably applicable to Guyana for the reasons outlined hereunder:

a) The ring fence tax of 30 per cent is equivalent to Guyana’s profit share and applied in the same manner as the 50 per cent profit share for Guyana. Notwithstanding, in the case of Guyana, ring fencing of the profit is not applicable because the oil companies operating in Guyana are strictly involved in exploration and extraction of oil and gas. In the UK, ring fence is necessary because the oil companies operating in the UK are involved in other trading activities apart from just exploration and extraction of oil and gas (such as the trading of refined crude products). The big oil companies such as ExxonMobil are involved in the downstream activities globally – hence this is where it becomes necessary to ring fence the profits.

b) The supplementary charge of 10 per cent applied to ring fence profits in the case of the UK is not comparatively applicable to Guyana given the explanation in (a) above.

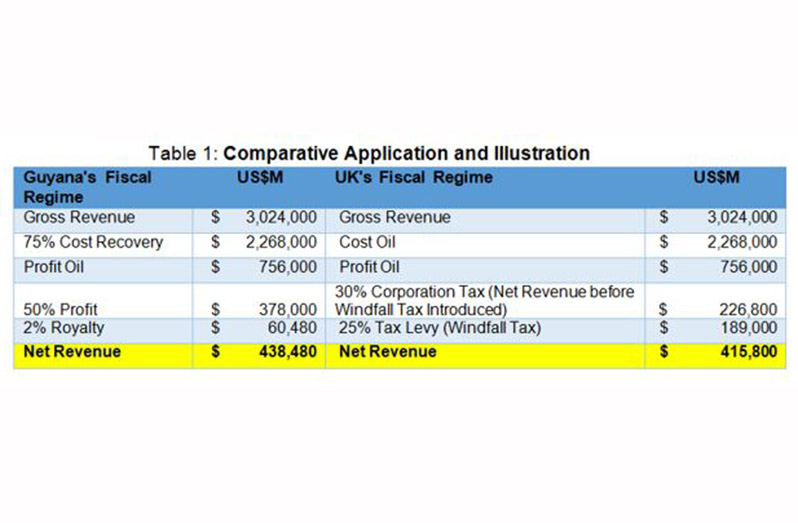

The table (1) above demonstrates the net revenue obtained under the current fiscal regime applied to Guyana versus the fiscal regime applied in the UK inclusive of the recently instituted windfall tax of 25 per cent. For the purpose of this demonstration the 10 per cent supplementary charge, ring fenced profit tax are not applicable by virtue of the explanations at (a) and (b) above. Further to note, as stated above the petroleum revenue tax which was previously 50 per cent in the UK was reduced to zero per cent in 2016, is also not applicable.

The table (1) above demonstrates the net revenue obtained under the current fiscal regime applied to Guyana versus the fiscal regime applied in the UK inclusive of the recently instituted windfall tax of 25 per cent. For the purpose of this demonstration the 10 per cent supplementary charge, ring fenced profit tax are not applicable by virtue of the explanations at (a) and (b) above. Further to note, as stated above the petroleum revenue tax which was previously 50 per cent in the UK was reduced to zero per cent in 2016, is also not applicable.

In view of the foregoing, table (1) above shows that before the application of the 25 per cent tax levy (windfall tax) in the UK in May of this year, only the 30 per cent corporation tax practically applies, and with a profit of US$756 million, the net take for the UK Government is US$226.8 million. Contrastingly, with the same profit oil of US$756 million, applying Guyana’s fiscal regime which is two per cent royalty and 50 per cent profit, Guyana’s Government net take amounts to US$438.5 million. This is US$211.7 million more than that obtained for the UK Government or 93.3 per cent more.

Furthermore, with the application of the 25 per cent windfall tax, the UK’s Government net take using the same scenario of profit oil amounting to US$756 million, the net take amounts to US$415.8 million which is still US$23 million less than Guyana’s Government’s net take.

The reason why Guyana’s Government take remains higher than the UK’s even when the UK applied the 25 per cent windfall tax is simply because the 25 per cent is an additional tax on top of the 30 per cent corporate tax which is applied only on the profit. In Guyana’s case, the profit share of 50 per cent is higher than the 30 per cent corporate tax rate in the UK and the royalty of two per cent is applied on the gross production of crude oil for sale which will naturally result in a higher share – on the gross production instead of only on the profit.

Another important fact to note is that oil and gas revenues in the UK have contributed 2.5 per cent of government’s total revenue for the period 1975 – 2010 (Grantham Research Institute, 2016). On the other hand, oil and gas revenues in Guyana based on projected revenues for 2022, represents 67 per cent of current revenue and in terms of total revenue inclusive of royalties and profit oil plus current revenue, represents 40 per cent of government’s total revenue for 2022.

In December 2020 with the brent crude price of US$51.8, Guyana earned US$51.8 million on every one-million barrels of crude paid in profit oil. As of June 2022, the brent crude price was US$114.8 or US$63 higher than in December 2020, Guyana earned US$114.8 million on every one-million barrels of crude paid in profit oil, representing US$63 million more than the amount earned in December 2020, on every one-million barrels of crude oil in profit oil.

In December 2020 with the brent crude price of US$51.8, Guyana earned US$51.8 million on every one-million barrels of crude paid in profit oil. As of June 2022, the brent crude price was US$114.8 or US$63 higher than in December 2020, Guyana earned US$114.8 million on every one-million barrels of crude paid in profit oil, representing US$63 million more than the amount earned in December 2020, on every one-million barrels of crude oil in profit oil.

The purpose of this illustration is to show that naturally, Guyana earned more in both profit oil and royalties due to the higher prices under the prevailing market conditions. Hence, there is no need for a windfall tax. Furthermore, as shown in this analysis, the situation in the UK is completely different from Guyana, the circumstance altogether in the UK justifies the need for a windfall tax. In contrast, the fiscal regime in Guyana allows for a higher take for the government even when compared to the UK’s fiscal regime inclusive of the windfall tax – that is to say, should the UK’s fiscal regime be applied to Guyana.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The comparative analysis contained herein demonstrates clearly that the economic situation and the fiscal regime for the oil and gas industry in the UK are completely different when compared to Guyana and Guyana altogether. In fact, the comparative assessment shows that Guyana’s fiscal regime allows for a relatively higher government take even when the 25 per cent windfall tax is applied to the fiscal regime as in the UK – that is to say, should the UK’s fiscal regime be applied to Guyana. The oil and gas revenue contributes just about 2.5 per cent of government’s total revenue in the UK while in Guyana the contribution to total revenue is about 40 per cent based on the projections for 2022.

The windfall tax was introduced in the UK because the fiscal regime over the years would have undergone several changes aimed at making the industry more competitive and to attract new investments in the industry. For example, the PRT was reduced from 50 per cent in 1993 to zero per cent in 2016.

More interestingly, while the fiscal regime in the UK is more sophisticated than Guyana’s, the UK’s fiscal regime is designed with a number of ‘built-in’ incentives. For example, the 25 per cent tax levy or windfall tax includes an additional investment allowance of 80 per cent that can be claimed at the point of investment. Overall, the tax relief companies receive from qualifying expenditure in the UK has nearly doubled from 46p for every £1 to 91p for every £1. Put differently, for every US$1 billion invested in the UK oil and gas industry, the oil companies receive US$912.5 million in tax relief under the new (current) scheme.

In the final analysis, there is no strong justification and merit for the application of a windfall tax in Guyana in view of the analysis presented herein, and especially since the brent crude price has already begun to hover below US$100″

———————————–

References:

1. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cost-of-living-support/energy-profits-levy-factsheet-26-may-2022

2. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/government-revenues-from-uk-oil-and-gas-production–2/statistics-of-government-revenues-from-uk-oil-and-gas-production-july-2022

3. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cost-of-living-support/energy-profits-levy-factsheet-26-may-2022.

.png)