By Tota C. Mangar

INDUSTRIAL action at Leonora escalated on Wednesday, February 15, 1939. Almost the entire field workforce joined in the strike, and took part in picketing exercises on both the ‘ sideline’ and ‘middle walk’ dams.

While factory workers initially reported for normal duty, the factory was brought to a standstill, as canes were not readily available for processing. The Leonora field workers then embarked on a plan to board the 7.40am train with their tools of trade and without tickets. They were eventually dissuaded from this aggressive response by a police detachment under Superintendent Webber.

The strikers subsequently proceeded on foot along the railway track to Vreed-en-Hoop, the eastern terminus of the West Coast of Demerara railway, and the point of embarkation of the Vreed-en-Hoop-Georgetown ferry. At Vreed-en-Hoop, the workers were addressed by C.R. Jacob. He promised them that the union would seek redress for their grievances, which included wage rates, hours of work and method of loading punts. This union official also advised the strikers to return to their homes. The protestors, however, were not satisfied with the union’s response; instead, they wanted an immediate settlement of their concerns.

C.R. Jacob departed for Georgetown to attend the afternoon’s sitting of the West Indian Royal Commission, and it appears as if his visit to Vreed-en-Hoop was largely ineffective. By about 1.30pm that very day, the striking workers were joined by another contingent, which was conspicuous by the dominance of females. While some were obviously the wives of striking sugar workers, it is reasonable to conclude that a good many of them were sugar workers themselves, as women then formed approximately 30 per cent of the field labour, and were very prominent in the weeding gangs.

The growing crowd of protesters renewed their efforts to cross to Georgetown, but were prevented from boarding the ‘M V. Pomeroon’ by a party of policemen. While the protesters chanted loudly, they were by no means violent. This fact was highlighted by Mr. Jacob, in his testimony before the West Indian Royal Commission, when he said, “They were discontented, but quite peaceful.”

By 4pm, it was clear that the situation at the Vreed-en-Hoop terminal had become chaotic. Twice the ferry had to make premature departures, and police reinforcements from the city and elsewhere did little to quell the protesters. The growing crowd intensified its efforts to board the ferry, but the police foiled their actions.

Some of the strikers then began to board the West Demerara train without tickets, after realising the difficulty in getting to the capital city. This act of boarding the train without tickets was certainly an act of civil disobedience, and such a defiant spirit must have convinced the police, rail and district authorities to accede to the workers demand for free transportation home.

Additional carriages were attached, and, following instructions from the Commissioner of Labour and Local Government, Mr Laing, the train with the striking workers departed for Leonora. Obviously, some of the strikers, if not all, must have viewed this development as a sort of moral victory.

CONFRONTATION

The unrest at Leonora worsened on the morning of Thursday, February 16, 1939. Very early on that day, a group of striking workers entered the sugar factory and urged factory workers to support the strike. It would appear that the strike call was heeded, as most of the factory workers, including the factory’s firemen who had earlier in the week protested, joined in the overall struggle.

With tension running high, a detachment of policemen, armed with rifles and batons and commanded by the District Superintendent of Police, arrived on the scene. The police presence seemed to have heightened the animosity of the striking workers. Some of them stoned the police bus, and they even resisted arrest.

Meanwhile, some strikers congregated near the Administrative Manager’s house and again demanded higher pay, and even requested the presence of union leaders Edun and Jacob. Lywood attempted to address the gathering, but was quickly greeted by flying debris; everything at Leonora was pointing to an explosive situation.

Incidents of sporadic violence increased as the day progressed, and the striking workers at Plantation Leonora once again demanded the presence of union officials. This demand, however, was not taken seriously, because of the estate administration’s refusal to allow the MPCA officials to enter the estate compound in the absence of a union recognition agreement.

The strikers subsequently moved towards the factory. In the meantime, the District Superintendent of Police instructed his men to prevent their entry into the factory at all costs. The workers continued to advance, while throwing missiles at the police. Constable Bijadder was pursued by a small party of labourers, and three policemen went to his rescue. Blows were exchanged between the striking workers and policemen, and injuries were sustained by both groups.

As the strikers became more and more threatening, orders were made to open fire on the ringleaders. The colonial police obeyed, and four strikers, including a woman, were killed, while four others were seriously injured.

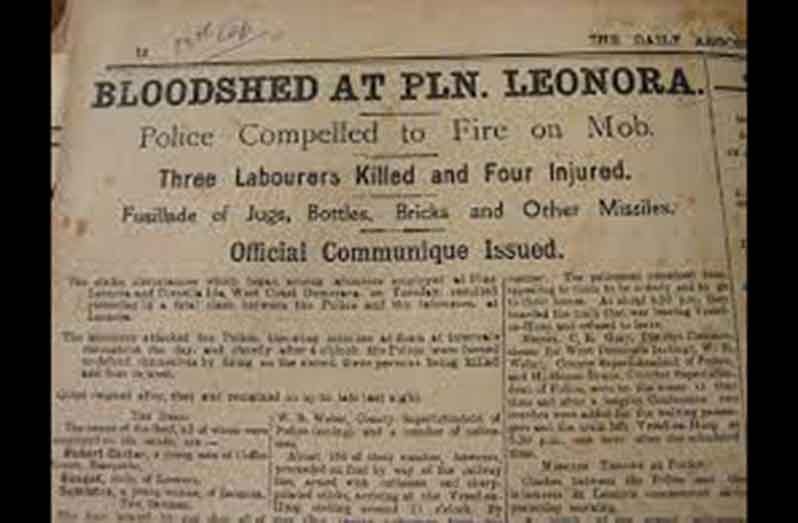

The crowd quickly dispersed, as people ran helter skelter, and the strikers were subdued. By the following day, the strike was over, and work eventually resumed at Plantation Leonora. Regarding the incident, The Daily Argosy of Friday 17 had as its headline, ‘Bloodshed at Leonora, police compelled to fire on mob’.

COMMISSION OF INQUIRY

Governor Wilfred Jackson promptly appointed a Commission of Inquiry to investigate the circumstances relating to the Leonora disturbances of 1939. The Commission of Inquiry comprised Chairman Justice Verity; First Puisne Judge, Mr. J.A. Luckhoo; and retired Immigration Agent-General, Mr Arthur Hill. According to Chairman Verity, the Commission of Inquiry “should be conducted thoroughly, but with expedition, and we rely on every person concerned to support us in our determination to do so”.

After 12 days of intense hearing involving the Police Department; the Demerara Company Limited; the relatives of the deceased, through the British Guiana East Indian Association and a total of 69 witnesses, the Commission laid blame on the Sugar Producers Association (SPA) for its failure to grant recognition to the MPCA. At the same time, it did not think that the existing conditions at Plantation Leonora justified the level of discontent of the workers.

CONCLUSION

The Leonora Strike and Riots of 1939, in the end, undoubtedly helped to hasten the recognition issue surrounding the MPCA, even though sugar workers were to be disenchanted with this very move in a few years’ time. This was evidenced in the late 1940s, when they broke away in favour of the Guiana Industrial Workers Union (GIWU), the forerunner of the Guyana Agricultural and General Workers Union (GAWU), with its most militant leadership and outlook.

The protest action was also significant, from the point of view that it witnessed the prominent roles of women and the unified action of field and factory workers, especially in the latter stages of the strike. It was another instance of supreme sacrifice paid by sugar workers in their quest for social and economic betterment.

The 1939 protest at Plantation Leonora was indeed part of a wider, ongoing working class struggle, and increasing political consciousness in this crucial pre-independence period of Guyana’s history.

.png)