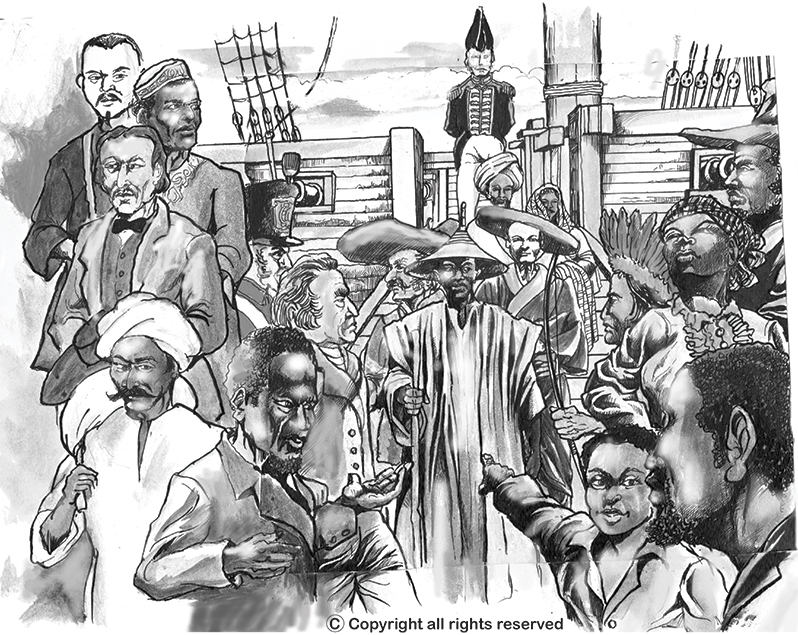

– The final chapter

“FOR too long has Guianese history remained in the background of historical studies in the country; we must now bring it into its rightful place in the foreground of social studies in our schools as well as within the knowledge of all adult Guianese.

History looks back on the past and brings our heritage and all the antecedents of our present position clearly before us.” Mr. C.V. Nunes Minister of Education, 1962; our predicament is that the obvious became subject to our inferiority complexes in respect to our own wise, and a causality of the experimentation with “Isms,” instead of colonising the “Isms: into our own context, we adopt another’s revolutionary cries and further bind ourselves to the hypocrisy of preaching one narrative while being obedient to another.

The antecedents of cultural and functional values that are bound to command questionable attention and suspicion at times will wrestle in a national arena, guided by separate rules because the guidelines of our timelines and its disruptions have not been adhered to.

Post Emancipation which I have coined years ago as… “The genesis of modern Guyana,” became the most conflicting era because up to then, forms and creeds were formulated and understood in a quarrelsome way, but after 250 years of harsh, hostile versus compromising engagements, this was inevitable. One example occurred with the slaves of Alness of the colony of Berbice and other plantations who took an oath that no cruel master should live beyond six months.

Post Emancipation which I have coined years ago as… “The genesis of modern Guyana,” became the most conflicting era because up to then, forms and creeds were formulated and understood in a quarrelsome way, but after 250 years of harsh, hostile versus compromising engagements, this was inevitable. One example occurred with the slaves of Alness of the colony of Berbice and other plantations who took an oath that no cruel master should live beyond six months.

The story of one such execution was revealed many years later by a very old slave as a parting testimony after all the actors were gone, leading to the discovery of the buried remains of the horse, saddle and the condemned plantation master, who had vanished for decades.

Suspicion was conveniently directed at the Maroons, but likewise, a young kind-hearted master came onto a neighbouring plantation and baffled the keepers of the oath; they were able to frighten him away with horrid tales, he returned to Europe, much to their relief. See- “A Documentary History of Slavery in Berbice 1796-1834 by Alvin Thompson.”

The values of the Creole community in respect to the established creed of belonging with the ‘being’ of ‘the colony’ post-emancipation, despite group identities would seem surprising, but there was an evolved national consensus of protected nationhood by Creole subjects, despite harsh conflicts with the colony administration, against whom they were not afraid to address their concerns; the first group of indentured people to attract discrimination from the administration and the Creole population on this pretext were the Portuguese; “ Most of the Portuguese were still Portuguese and not British subjects; though resident in a British colony for years, they did not wish to become naturalised.

No wonder they were considered aliens. They still considered themselves “sons and daughters” of Portugal and this attitude did not win them friends as in maintaining their separateness they tended to be smug see- “The Portuguese of Guyana: A Study in Culture and Conflict by Mary Noel Menezes, R.S.M.”

The fact is, that with Indentureship it must never escape consideration that British interests were riveted to establishing an empire, and with most of the indentured coming from then British colonies and friendly states, they were more likely to accommodate levels of social responsibility towards the contract -societies, while with the Creole population that constituted manumitted slaves, kith and kin who were British colony subjects no external mother country presided over their interests and rights, they were akin in pursuit of rights with the poor of England itself.

Unlike the indentured, the manumitted Africans had emerged from slavery; the enslaved Africans were from inception abandoned to their fate; thus, after emancipation, to shape a new cultural and survival ethos, to value their peculiar history towards interpreting reciprocal economic rights, while recognising their unique process of ‘Being’ cognisant of an evolved difference, and world view identity; while in the environment of the indentured worker, the simple pretext was to have their rights throughout their contracts guarded by the authorities and sub authorities of the mother country.

To embrace and envelop the alien world he/she was contracted to, did not seem to be an intended motive in most cases, except in cases where some individuals understood that cultural differences existed in the colonies that allowed opportunities in a new land that were not permitted in the age-old traditions of the ancestral place, as indicated-“ The rigours of the caste system, agrestic slavery, population density and limited economic activity in some districts were some of the main catalysts for the emigration of Madrasis as indentured labourers to Guyana and other countries- Though the caste system was the canker of the Hindu society, the worse elements of it were nowhere more conspicuous than in the presidency of Madras, more especially so in Tamil Nadu, where the entire population other than the Brahmins were reduced to the position of Sudras, though social realities were different.” See “History Gazette #16, 1990 A Preliminary Study of the Madrasis of Guyana by Ph.D. E. Sa Visswanathan.”

Though the Chinese are less in our dialogue, had no known racial philosophy divisive against the Creoles or other indentured groups, they were among the first to have Secret societies that organised with both criminal and civil economic niches, Gambling and opium dens. -see Cultural Power, Resistance…-by Brian.L.Moore;

Rather than spend money to send indentured labour to their motherlands, the authorities encouraged settlement (the context of the settlement is not quite clear). Government-sponsored villages were allotted to the Chinese, their village was at Kumuni Creek named ‘Hopetown’ while for the Indians, Plantation Huis t’dieren in Essequibo.

A settlement was opened at Helena, Mahaica, Whim, Bush Lot and Maria’s Pleasure. See- The Village Movement 1839-1889 by David A. Granger: It must be noted in closing, that from a holistic overview of that era, the only groups that did not benefit in perspective from colony concessions were the manumitted Africans and their kith and kin, but concessions were extended not through altruism, but purely through stringent fiscal considerations. Literature is cited in this and other articles to encourage independent extended research of the topics.

.png)