The era of indentureship in reshaping the colony of British Guiana Pt II

THE first article indicated the origins of our “state” in only the broad sense that articles such as this will permit. I have chosen to explore the cultural beings that constitute the “shaping” and the “reshaping” of the colony. It is recorded that there is no area of potential that has been fought over like the so-called New World (which it isn’t).

By emancipation the colony was shaped in the cultural construct of a Creole entity; the dictates of the Creole world constituted two aspects: the development of the “colonial”, which is a cultural and philosophical construct that held its former cultural self in contempt, and had reoriented its values along superficial pretentions and loyalties befitting a supernatural possession by the damned spirits of former oppressive dictates, in need of a scapegoat to project evaluations of its current “social being.” The other, who acknowledges the fact of the cultural fusion of ideas, yet evolves its own essence and values as an undeniable prototypical contribution.

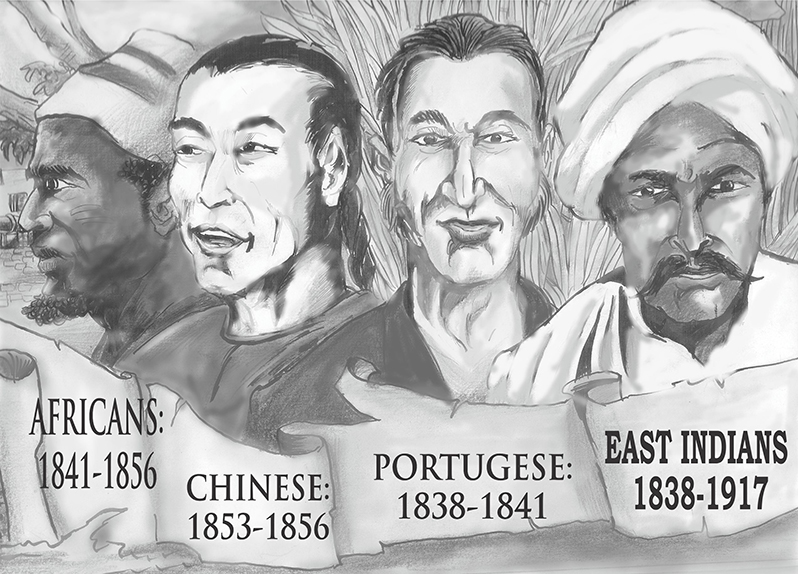

The crisis of the old slavery-driven labour in sugar, was of great economic concern at the threshold of England’s “Industrial Revolution’s” coming of age. Thus, the planter administration of the colonies engaged in the recruitment of contractual labour prior to 1838. This was not by any chance a process without event from its inception, affecting contractual labour and the social existence of colony citizen labour. The planter colony administration intended to implement this system at the least of their expense, and to maintain cheap labour in an atmosphere of peace and tranquillity,void of humanity and justice.

They looked to the colony of India, with its severe caste system inequalities, the impoverishment colonisation had heaped upon it, to draw an example, by the dumping of British manufactured goods that eliminated local production. They did not equally desire labour from the African pool after the experiences of the labour strikes of 1842, when the contracted labour from Sierra Leone supported the manumitted Afro-colony work force, as their social platform was not the same as the East Indian. There were much more satisfied with the response of the Portuguese and East Indian contract workers in the strikes of 1848, the probable mindset of these labourers were concentrated on their mission to make money and return to their homelands, and not to be involved in local contentions, thus, they did not support that strike; the churches also had betrayed their major Afro-village congregation, adhering instead to the concerns of the planters.

The contentions of the manumitted colony citizen was based on wages and rights and more so, the fact that the Villages were required to pay taxes for drainage works, upon doing this the planter administration used most of their taxes to import labour; these actions had tremendous effects on the social being of the villages. We look to a later report on that era that consists of some 50 years…

A-“On the whole, in the 1920s, despite their many shortcomings, the estates did infinitely more to protect the health of their Indian labourers than the colonial authorities did for the villagers. The miserly, often inadequate contribution of the former looks good against the “puny efforts” of the government, “a standing reproach to any community.” The villagers had to pay a fee at government hospitals; often, the sick had to travel long distances over impassable roads. And as the Surgeon General reported in 1922 and 1923, sanitation in the villages was backward and the residents were reduced to an aquatic existence during the heavy rains, because of a lack of drainage.

The drinking water was often contaminated, the source was an open trench befouled in the most abominable way. Toilets were primitive; the contents of these seeped into the drinking water ponds during frequent floods. In the drought of 1926, man and beast competed for the brackish slimy green water in residual pools. On the sugar estates the canals were deeper, and subject to replenishment by creek and backdam water in the dry season.

The drinking water, though impure, was better. A contemporary observer remarked that a serious handicap to estate residents was the continual re-infection by adjacent villages, where no sanitation existed at all. A malarial sluggishness characterised colonial attitudes to drainage and irrigation, sanitation and “the demon of malaria” which was accepted by Keatinge in 1922, as the most serious evil in the colony.”

B- “Apart from the perils of the journey itself, [ that included cholera, due to bad water supplies on board] –with few exceptions the workers were treated with great severity. Their accommodations were either too confined and disgustingly filthy, or none were provided, and in cases of sickness there was the most culpable neglect. Disease was rampant. There were yellow fever, malaria, dysentery, cholera, hookworm, to name a few.” Indian History Congress-JSTOR vol. 74 by Mukesh Kumar-{extracts}. The indentured came with distinct and in some cases opposing cultures, with the Chinese and Portuguese it was less a cultural hindrance to merge with the Creole community, which as indicated was itself not cohesive.

With the Indian, after the episode with the 1838 arrivals who were not contained in strict boundary yards, had embraced Creole[ Afro] women and upon severe ill-treatment and a cultural change merged with the adjacent villages, the planters created the estate world, separate and culturally controllable.

Thus, the beginnings of deep cultural and socially isolation. As in closing, one observation must be echoed. “The regretted public ignorance of the extent to which the disease “saps the vitality of the population” this deep-seated complacency embraced all: at no time did the British Guiana East Indian Association or the Negro Progress Convention manifest a knowledge of the pervasively negative impact of malaria on society; nor did they urge the authorities to work towards its eradication- Mukesh Kumar-{extract}.