By Ian Chappell

They are panicking and trying to attack from the crease rather than stepping out to get the bowler to change length

VIRAT Kohli described the recent day-night third Test, in Ahmedabad, as “bizarre”, a word that aptly describes the England batsmen’s attempts to cope with India’s spinners.

India’s decision to select three spinners for the Test was prompted by England’s batting on a tricky Chennai pitch, where their batsmen – Joe Root excepted – displayed a distinct ineptitude against spin. India correctly calculated that would result in mental scarring and used it to their advantage.

From the moment Axar Patel conjured up the ultimate thimble-and-pea trick to dismiss Jonny Bairstow with a straight delivery, England were in a spin. Is the ball over there? No, it’s here.

When faced with a serious spin challenge, the England batsmen didn’t trust their defence, which eventually resulted in panicked attempts to attack the Indian spinners. Their choice to reverse-sweep rather than to leave their crease to change the bowler’s length is a classic example.

How can a risky premeditated shot be less dangerous than what was previously a trusted technique to unsettle good spinners?

One of the first principles of batting – especially on a pitch assisting spinners – is to keep the odds slightly in your favour.

Following the memorable 2000-01 series in India where VVS Laxman made a magnificent 281 on a testing surface, I asked Shane Warne how he thought he had performed. “I didn’t think I bowled badly,” he replied. “You didn’t,” was my response. “When a batsman alters your length drastically by coming out three paces and then is quickly onto the back foot when you toss the next delivery a little higher and shorter, that’s not bad bowling, that’s excellent footwork.”

Shrewd use of footwork not only helps negate the spin but also puts a batsman in a position to direct the ball where he wants, rather than where the bowler would prefer it to be hit.

To be fair, this is a skill to be learned at a young age. Which prompts the question: why is it not widely taught in England, where sweeping is misguidedly touted as the secret to playing spin bowling successfully?

Another prominent theory is to take block on off stump when the ball is spinning back in to the batsman.

This flawed theory closes off scoring opportunities through the on side. It’s designed to reduce the chances of being dismissed rather than to create scoring opportunities, which is always a bad option. It also causes batsmen to play balls towards leg slip. Why deliberately hit the ball where there’s a catching fielder?

I asked former Australia batsman Doug Walters: “How do you get caught at leg slip when an offspinner is bowling?”

“You can’t,” he replied.

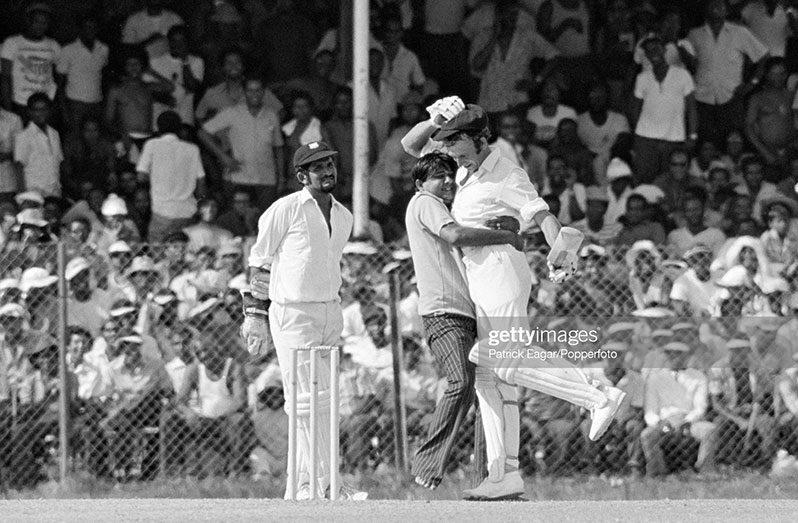

Walters is the best batsman I’ve seen against top-class offspin bowling. He scored a century in a session on a tricky Queen’s Park Oval pitch against Lance Gibbs and crafted a brilliant hundred against Erapalli Prasanna on a Chepauk pitch that was every bit as difficult as the one in the recent Test there between India and England.

On both occasions he used lightning quick footwork to both negate the spin and manipulate the field placings against two champion offspin bowlers.

Back in Ahmedabad, Ollie Pope decided to use his feet against the Indian spinners. He had the right idea but the wrong execution. Firstly, he jumped rather than glided out of the crease. Secondly, his front foot pressed forward but the back one lingered, as if searching for the safety of the crease.

I was told two crucial things about footwork when I was very young: “Get stumped by three yards not three inches,” my coach said, “and never think about the keeper when you leave the crease.”

Pope was conscious of the keeper as he tentatively ventured out of his crease, which meant he was worried he would miss the delivery. That results in footwork that hinders rather than helps.

It’s never easy against good spinners on a challenging surface, but it is possible to play well; just not the way England are going about it

(Cricinfo).

.jpg)