– A look back at the Un|Fixed Homeland exhibition

“A man travels the world over in search of what he needs and returns home to find it.” ―

George Moore from The Brook Kerith.

Although these “needs” vary from person to person, it is precisely this movement between spaces both familiar and alien, driven by the desire to seek out more for ourselves and our families, that came under investigation in the recently concluded exhibition of photographic works aptly titled Un|Fixed Homeland.

Thirteen artists with varying connections to Guyana engaged with themes of displacement and the Guyanese identity in an expansive and equally impressive collection of works at the Aljira Center for Contemporary Art in Newark, New Jersey.

Grace Aneiza Ali, curator of the Un|Fixed Homeland exhibition, described migration as “one of the most defining movements of our time,” and it’s hardly a surprise at all.

In fact, were you to take a quick trip down to the main immigration office, located on Camp Street, Georgetown, and it would immediately become apparent that the Guyanese identity is still very much shaped by mass exodus now as it was decades ago.

At 05:00 a.m. on any given day, there would be at least 50 persons standing in line along the side of the road, waiting for the doors to swing open at 07:00 a.m. and the immigration officers to start processing their documents.

Just three months ago, I was in that line for two days before I finally got a new passport. The line stretched around the corner onto Eve Leary

with persons from all walks of life waiting, hoping to secure the ticket that halfway-ensured escape (be it temporary or otherwise) from their current lived experience.

On the first day, the sun had barely risen when disappointment and anger swept over everyone’s face after realizing they would have to go through this process again the following week. Some had been traveling since the day before from the furthest regions of the country only to be turned away an hour before the doors officially opened. Quite a few persons expressed their disgust at the tiresome process, saying it had been their third or fourth unsuccessful trip to Georgetown.

“Next time come earlier!” someone shouted from the head of the line.

Naturally, that did very little to quell the mounting frustration. At the time it seemed a strange metaphor for something much larger than what my sleep-deprived brain was willing to contemplate. Like everyone else, I was annoyed that old men, pregnant women, restless children and everyone in between were forced to stand on the road, exposed to the elements, traffic and a slightly threatening character who, apparently, spent every morning cursing “jezebels” for wearing pants and makeup.

Guyana’s history of voluntary and forced migration is often examined from the perspective of politics: The main agitator in a story about the unfulfilled potential of a country torn at the seams by racial tension. The simple answer to the question of why we choose to move, whether for a month or a lifetime, is almost always

a version of “I want better for my family.” For those persons who choose to uproot themselves, this desire to do more for their family overshadows any uncertainty or risk involved in being transplanted into a new and unfamiliar space.

The “why” is also perhaps far less interesting than the question “what happens next?” How do these migrants adapt to their new environment while still maintaining their connection to home? What gets lost or abandoned en route to this new home?

Ali describes this process of “sustaining the vulnerable threads to homeland” as “beautiful, fraught, disruptive, and evolving.” What better way to begin unraveling the complexities of migration from our shores than by looking at works produced in response to that concept of “place and placelessness” as she describes it?

How have these creative practitioners held on to their memories of this space and the stories recounted by their parents? How have they pieced together the fractured memories of a place that has been weathered by waves of transformation and yet ironically, managed (in more ways) to remain unchanged? How do gender and religion factor into this equation, if at all? How important is it that we document the depressed footpaths in the earth that map various routes in and out of this place we call “home”? These are all questions that would have, at some point, confronted viewers as they hitched a ride on the journey to Guyana and back.

The exhibition proposed that this “homeland” in question could be both fixed and unfixed, a “constantly shifting idea and memory, a physical place and a psychic space.” Each artist’s unique point of entry may have originated from a solitary environment but what resulted was the culmination of a collective history that allowed both the makers and viewers to see a little or a lot of themselves in each other’s narrative.

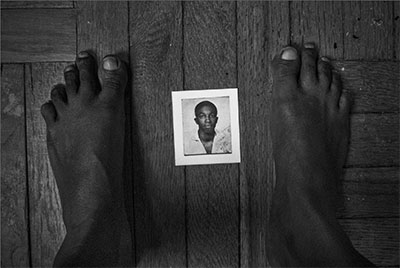

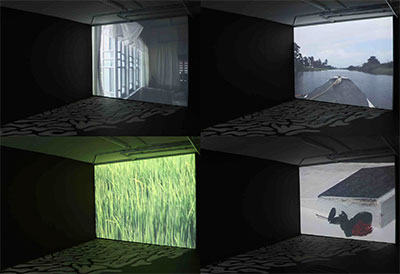

Speaking on the relationship between each artist’s approach and theme of the exhibition Ali described their engagement with photography, particularly “[…] the archival image of British Guiana, contemporary photography on present-day Guyana, self-portraiture, studio portraiture, painted photographs, passport photos, family albums, selfies, photography in video installations, and the documentary format, among others” as the vehicle used to “unpack the global realities of migration, tease out symbols of decay and loss, and explore the experiences of displacement and dislocation.”

Ali goes on to say, “The artists in Un|Fixed Homeland intimately understand this liminal space of leaving and returning. As they represent both the ones who leave and the ones who are left, these artists examine what survives and what is mourned.”

This being the year of our 50th Independence Anniversary, our Golden Jubilee, the exhibition coincided perfectly with the period when hundreds of thousands of Guyanese worldwide took time to consider the aspects of our identity that warranted celebration and the parts in desperate need of repair. The works on display offered a much more critical and pointed assessment of self and citizenship as it provided a platform not only for practitioners in the diaspora to engage with feelings of displacement, but also to local practitioners who might have been disillusioned by their proximity to the problems that continue to plague our country’s development.

Regarding the global perception of Guyana’s visual culture Ali believes that it “centers on the exotic, the tropical, the colonial, and the touristic.” Un|Fixed Homeland, she says, aimed to “counter this historic malpractice by challenging, disrupting, manipulating, and even exploiting the ‘picturing paradise’ motif often associated with the region.” Far beyond that, the structure of the exhibition allowed Guyana to become a metaphor for much larger and more urgent “universal concerns” that underscored “the tensions between place and placelessness, nationality and belonging, immigrant and citizen.”

Un|Fixed Homeland opened on July 17 at the Aljira Center for Contemporary Art in Newark, New Jersey and closed on September 17, 2016. The exhibition featured photographic works from artists Erika DeFreitas (Canada), Sandra Brewster (Canada), Karran Sahadeo (Canada), Khadija Benn (Guyana), Michael Lam (Guyana), Frank Bowling OBE RA (United Kingdom), Roshini Kempadoo (United Kingdom), Hew Locke (United Kingdom), Kwesi Abbensetts (United States), Marlon Forrester (United States), Donald Locke (1930 – 2010, United States), Maya Mackrandilal (United States) and Keisha Scarville (United States).

| Guyanese-born curator Grace Aneiza Ali is the recipient of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts Curatorial Fellowship. She has spent her fellowship researching the canon of contemporary Guyanese artists, which still remains largely unknown on the world stage. Ali is a faculty member in the Department of Art & Public Policy, Tisch School of the Arts, New York University and the Editorial Director of OF NOTE —an award-winning online magazine on art and activism. Her essays on contemporary art and photography have been published in Nueva Luz Journal, Small Axe Journal, among others. Highlights of her curatorial work include Guest Curator for the 2014 Addis Foto Fest; Guest Curator of the Fall 2013 Nueva Luz Photographic Journal; and Host of the ‘Visually Speaking’ photojournalism series at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center. Ali is a World Economic Forum ‘Global Shaper’ and Fulbright Scholar. She holds an M.A. in Africana Studies from New York University and a B.A. in English Literature from the University of Maryland, College Park. |

.png)