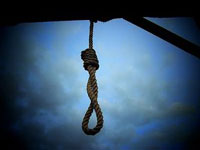

THE stage curtains open. Six nooses hang above the young inmates, who are making chairs in the prison workshop to be used as the platforms in their own hangings. The audience gasps.

This is theatre that is intended to be raw, edgy and political. What’s even more jolting for some in the Tehran audience is that it’s all been cleared by Iranian authorities.

This is theatre that is intended to be raw, edgy and political. What’s even more jolting for some in the Tehran audience is that it’s all been cleared by Iranian authorities.

The production, translated from Farsi as “The Blue Feeling of Death,” opened last month as a showcase of activist art against Iran’s legal codes that allow death sentences for children, who then wait until their 18th birthday for possible execution.

Opening night came, even as Iranian officials tightened controls on the social media and other forms of political opposition before presidential elections, whose centrist winner, Hasan Rouhani, has brought hope of reversing some of the crackdowns.

The play tells the true stories of seven juvenile death row inmates and the families on all sides of the crime. It also seeks to raise funds for defense lawyers and social workers trying to remove death sentences on young people through Iran’s system that allows families of victims to spare the life of the prisoner, usually by payments.

“Through the stage, we can affect many people; even the families of victims,” said the play’s director, Amin Miri, following a recent performance. “We are trying to give greater courage.” The play also shows the unpredictable enforcement of Iran’s cultural overseers.

Dozens of journalists, filmmakers and others have been arrested or forced to flee the country in recent years over allegations of opposing Iran’s Islamic establishment, or stirring political dissent. These red lines still exist, but officials can give their nod to works exploring social issues, or other topics that don’t directly target the ruling clerics.

In 2008, a documentary filmmaker had permission to research Iran’s rising number of sex-change operations, which have been legal under a religious edict, or fatwa, shortly after the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

The 2012 Oscar-winning film, “A Separation”, by Asghar Farhadi, was hailed by Iranian authorities, although its plot is a harsh commentary on Iranian society, through the viewpoint of a collapsing marriage.

In 2003, Farhadi directed “Shahr-e Ziba”, the name of the neighbourhood where the Tehran Correction Centre is located, to portray the destinies of young convicts, as well as the families of victims.

But last year, Iranian officials ordered the closure of the House of Cinema, an independent film group that had operated for 20 years, and counted Iran’s top filmmakers, including Farhadi, among its members. The site has remained closed because of hard-liner pressures, despite a ruling to allow its reopening.

“Blue Feeling” has been able to walk the line between criticizing the legal codes that allow the death sentences on young people — a practice also condemned by Amnesty International and other rights groups — and showing there are options in Iran’s system for mercy.

Once a death sentence is imposed in cases of murder, the victim’s family can withdraw the punishment in place of jail time, and often, payments known throughout the Islamic world as “blood money”.

The director, Miri, said 18 death row inmates — some as young as 15 — were interviewed to build the stage stories. He was inspired by a move by some judges to postpone carrying out the hangings for inmates, once they reached 18, in hopes of persuading the victims’ families to withdraw the punishment.

Among the stories in production are two young girls sentenced to death for killing their father when they were 12 and 15. The persons holding the key to whether the sentences would be carried out were an uncle, aunt and grandmother.

“I felt as if I was communicating the message of the play when I heard and saw the reactions from the audience,” said Mina Karimi Jebeli, who played the role of one of the young murderers.

At a recent performance at the Arasbaran Cultural Centre in north Tehran, some of the theatergoers sobbed. “It was very emotional,” said Arezou Ziaei, 23. “I cannot believe that such people are waiting for death.”

Executions in Iran are increasingly carried out in prison gallows — often with a chair or bench kicked out from under the inmate — but public hangings still occur with the condemned prisoner hoisted up by a crane attached to the rope and noose.

In the past, the age of criminal responsibility in Iran was defined by “maturity”, which is nine for girls, and 15 for boys. Iran’s parliament amended laws in 2011 to block death penalty sentences on anyone under 15, and give judges more leeway to impose substitute sentences on juveniles convicted of murder.

While the number of juveniles sentenced to death in Iran is relatively small, rights groups say it violates international treaties on treatment of young suspects.

In January, a 21-year-old Iranian man was reportedly executed for his alleged role in a murder when he was 17 years old, activist groups say. And in 2012, at least one of the more than 300 people executed in Iran was sentenced as a juvenile.

Two other countries, namely Saudi Arabia and Sudan, are known to have executed someone in recent years for a crime committed before they were 18, according to New York-based Human Rights Watch. Last September, Ahmed Shaheed, the U.N. special rapporteur on Iran, urged Iranian authorities to abolish capital punishment in juvenile cases.

Lawyer Nemat Ahmadi welcomed the performance as a chance to push lawmakers and authorities to contemplate further judicial reforms. “Such a play,” he said, “is able to awake public opinion.” (Sowetan)

.png)