…Guyana argues in presenting case for full and final settlement

By Svetlana Marshall

IN rejecting Venezuela’s contention that the International Court of Justice (ICJ) has no jurisdiction to confirm the legal validity and binding effect of the 1899 Arbitral Award, Guyana, in a presentation before the Court, said the 1966 Geneva Agreement, in unambiguous terms, empowered the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General to determine an appropriate dispute resolution mechanism to enable a peaceful settlement.

It was on that basis, the country argued, that the UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, rightfully referred the border controversy, which stemmed from Venezuela’s contention that the 1899 Arbitral Award was null and void, to the ICJ in 2018 for final settlement.

Guyana, in its virtual presentation before the panel of judges led by the President of the ICJ, Abdulqawi Yusuf, in the case – Arbitral Award of October 1899 (Guyana v. Venezuela), said that, not only is Venezuela’s current interpretation of the Geneva Agreement illogical and erroneous, but it is in stark contrast to the interpretation the Spanish speaking country had when it signed the very agreement in February, 1966.

Guyana’s Co-Agent, Sir Shridath Ramphal, and a battery of international lawyers, told the ICJ, on Tuesday (June 30), that the UN Secretary-General resorted to the Court after the Mixed Commission (1966-1970), a 12-year moratorium (1970-1982), a seven-year process of consultations on a means of settlement (1983-1990), and the Good Offices Process (1990-2017) failed to resolve the controversy.

Venezuela, after more than 60 years of the issuance of the 1899 Arbitral Award, contended that it was null and void. The 1899 Arbitral Award legally established the location of the land boundary between then British Guiana and Venezuela. Guyana has long maintained that the award was a full, perfect and final settlement and therefore remains valid to this day.

RESOLVING THE CONTROVERSY

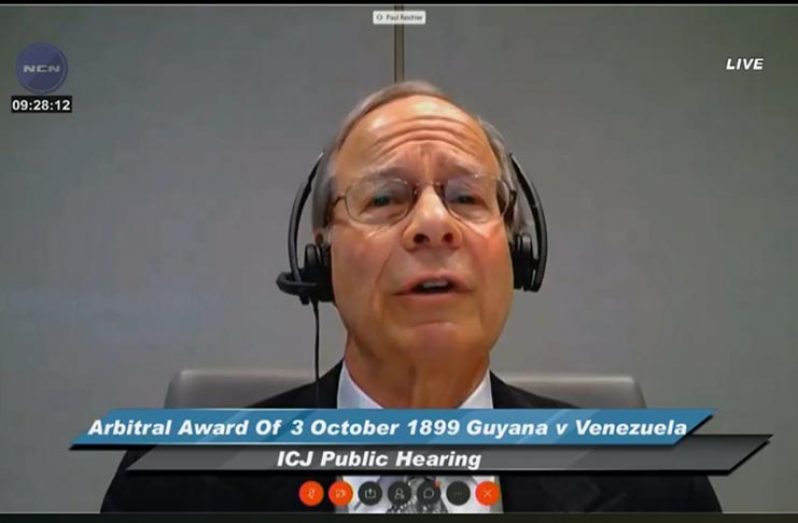

Internationally recognised Legal Counsel, Paul Reichler, who formed part of the battery of lawyers representing Guyana, told the ICJ that the primary purpose of the 1966 Geneva Agreement was to resolve the controversy between Venezuela and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland over the frontier between Venezuela and British Guiana.

Key in the agreement, he emphasised, was the objective to resolve the controversy.

In laying the foundation of his arguments on the issue of jurisdiction, Reichler explained that Articles 1, 2 and 3 of the 1966 Geneva Agreement outlined the role and responsibilities of the Mixed Commission. Under the agreement, the Mixed Commission was tasked with the responsibility of seeking satisfactory solutions for the practical settlement of the controversy.

But the Geneva Agreement, he pointed out, did not stop there, it entails five other articles, and of significant importance to the case, Article IV (2).

Article IV (2) states: “If, within three months of receiving the final report, the Government of Guyana and the Government of Venezuela should not have reached agreement regarding the choice of one of the means of settlement provided in Article 33 of the Charter of the United Nations, they shall refer the decision as to the means of settlement to an appropriate international organ upon which they both agree or, failing agreement on this point, to the Secretary-General of the United Nations. If the means so chosen does not lead to a solution of the controversy, the said organ, or, as the case may be, the Secretary-General of the United Nations shall choose another of the means stipulated in Article 33 of the Charter of the United Nations, and so on until the controversy has been resolved or until all the means of peaceful settlement contemplated have been exhausted.”

Reichler told the judges that it was key to note that Guyana and Venezuela have not disputed the fact that the Mixed Commission did not arrive at an agreement for the solution of the controversy, and that the governments had not reached an agreement on the means of peaceful settlement under Article 33 of the Charter.

These facts, the Legal Counsel said, are confirmed in Venezuela’s Memorandum, which was submitted in November, 2019. In support of his argument, Reichler pointed to paragraph 32 of Venezuela’s Memorandum, in which it said: “Venezuela and Guyana failed to agree on the choice of a means of settlement and to designate an ‘appropriate international organ’ to proceed to do it, as provided for in the first subparagraph of Article IV (2) of the agreement…”

Embedded in the Article he said is procedure for resolving the controversy in the event of an impasse. The Legal Counsel said not only that the countries had failed to reach an agreement on an international organ to choose the means of settlement, but in compliance with Article IV (2) they jointly referred the decision as to the means of settlement to the Secretary-General. Added to that, he said it is an undisputed fact that the Secretary-General formally accepted the parties’ conveyance of authority to him to decide on the means of settlement under Article 33 of the Charter, and agreed to exercise the responsibilities conferred upon him.

Notably, in a letter dated April 4, 1966, the then UN Secretary-General, U Thant, accepted the functions outlined in Article IV (2) of the Geneva Agreement.

In accordance with the agreement, in 1990, the UN Secretary-General, at the time, identified Good Offices Process as the first means of settlement – a decision that was embraced by the parties involved. However, the Good Offices Process, which spanned from 1990-2017 bore little or no fruit.

Reichler said it was after the Good Offices Process, after 27 years, failed to resolve the controversy that UN Secretary-General António Guterres invoked his authority under Article IV (2) and decided that the next means of peaceful settlement of the controversy under Article 33 of the Charter, shall be judicial settlement by the ICJ. These facts, he submitted to the Court, are included in Venezuela’s Memorandum of November, 2019.

The Secretary-General’s decision, he further submitted, is binding on both Guyana and Venezuela and ought to be respected. “It (Article IV (2) does not say that the decision of the Secretary General is subject to the subsequent agreements of the parties or that such agreement is required for his decision to be final or binding upon them,” the Legal Counsel told the Court.

VENEZUELA’S INITIAL POSITION

Reichler told the ICJ that Venezuela’s objection to the Secretary-General referring the controversy to the ICJ is not only illogical but goes against the position of its Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ignacio Iribarren Borges, who had signed the agreement in Geneva in 1966.

The Legal Counsel pointed out that the Venezuelan Foreign Minister, in his address to the Venezuelan National Congress in March 17, 1966, in his quest to have the Geneva Agreement ratified, said: “Finally, in an attempt to seek a respectable solution to this problem I put forward a third Venezuelan proposal that would lead to the solution for the borderline issue in three consecutive stages, each with their respective timeframe, with the requirement that there had to be an end to the process: a) a Mixed Commission, b) Mediation; c) international arbitration.”

Borges, Reichler said, was keen on pointing out to the Venezuelan National Congress at the time, “that there exists an unequivocal interpretation that [the] only person participating in the selection of the means of solution will be the Secretary General of the United Nations and not the Assembly.”

The Legal Counsel submitted to the ICJ that it was Venezuela who had proposed that Article IV be drafted so as to ensure a definitive resolution of the controversy ultimately, if so decided by the Secretary General by arbitration or recourse to the International Court of Justice.

“There is thus no doubt, Mr President, from the terms of the agreement, the negotiating history or the statements by the parties immediately following its conclusion that Article IV (2) was intended to assure that there would be a final resolution of the border controversy, that the Secretary General was empowered to decide on the means of settlement to be employed, choosing among those listed in Article 33 of the Charter and that the parties understood and intended that if the Secretary-General so decided that the controversy would be settled by the ICJ,” Reichler said.

He added: “This was Venezuela’s understanding of the Geneva’s agreement and of Article IV (2) in particular at the time it signed and ratified the agreement in 1966 that he Secretary General was empowered to decide on the means of settlement including recourse to the ICJ and his decision would be final and binding on the parties.”

Reichler told the Court that Venezuela’s President, Nicolás Maduro, was therefore wrong to suggest that the Geneva Agreement provides for border controversy to be resolved by the two countries only through friendly negotiations. He noted that none of Venezuela’s objections to the Court’s jurisdiction have merit.

Attorney-at-Law Philippe Sands, in his presentation, told the ICJ that all the conditions established by the Geneva Agreement were properly implemented and in accordance with those provisions, the UN Secretary-General, from 1983, was entrusted by the parties to determine the means of settlement of the controversy. He too pointed out that it was after more than 25 years of the Good Offices Process, that the UN Secretary-General, in 2018, selected the ICJ as the means of settlement.

Such decision was carefully considered and most importantly lawful, Sands told the Court. “The Secretary-General’s decision was appropriate and inevitable. It was a recognition of the need to bring a fair and final end to a long-standing and destabilizing controversy,” Sands told the judges. He submitted that the UN Secretary-General could not have gone on with the Good Offices Process indefinitely even as Guyana stood a victim of acts of aggression at the hands of Venezuela.

“Mr President, Members of the Court, the record is clear, more than 50 years have passed since the signing of the agreement. Four years were fruitlessly spent before a Mixed Commission (1966-1970); 12 years were then spent on an equally unavailing suspension of the Geneva Agreement from 1970-1982; 37 years ago this week, Guyana and Venezuela jointly entrusted the Secretary General with exclusive, unfettered and irrevocable responsibility of selecting the means of settlement of the controversy. After six years of further discussions between the parties and the Secretary General’s representatives, the Good Offices Process was established in 1990 with enhanced mandate of mediation for the year 2017. That means of settlement ran its course for more than a quarter of a century [and] it has produced no progress whatsoever,” Sands told the Court.

During the Good Offices Process and the other dispute resolution mechanisms, which were employed, there have been several incidents involving military force, coercion and bullying by the Spanish-speaking country against Guyana. Military Force and the threat of force included Ankoko Island, Cuyuni occupation (1966); the Sponsored Rupununi uprising 1969; the Leoni Decree – the attempt to seize territorial sea (1968); assault on Eteringbang outpost 1970 and innumerable subsequent military acts; the military seizure of Technics Perdana — seismic survey vessel of Anadarko in 2013; and most recently, the attempted boarding of seismic vessel Ramform Tethys (December 22, 2018).

Meanwhile, in offering opening remarks, Sri Shridath told the ICJ that the case is of significant importance to the people of Guyana who are united in their defence of their sovereignty and territorial integrity of their homeland.

Reichler, Sands and Sir Shridath presented alongside Payam Akhavan, and Alain Pellet – all of whom are international recognized legal luminaries. In a string of convincing arguments, they submitted that the ICJ had jurisdiction to hear the case, and should proceed to hear the substantive matter. The hearing was conducted at the Peace Palace in The Hague with virtual presentations being done by Guyana in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Guyana’s Agent, Carl Greenidge, who led the delegation and Representative of the Opposition, Gail Teixeira; Ambassador Audrey Waddell; former Minister of Foreign Affairs, Rashleigh Jackson and Ambassador Cedric Joseph, listened to the hearing from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Georgetown. The ICJ said it will announce a date for the ruling on jurisdiction shortly.

.jpg)