A bio-chronicle of trial and turbulent awakenings, Part I

LIKE most children growing up in Guyana, there was a fascination with picture magazines and comic books. But the first challenge or gesture thrown at me came in 1973 when the Kuru Kuru Co-op College was officially opened (some years ago Robert Persaud, then a PPP Minister, referred to that facility as a political-orientation centre – it was never that).

It was an institution that saw students from the Caribbean and the resurgence of the local co-op movement. We (pioneers) had worked on the construction of the college. We lived in spartan barrack rooms, and when the beds and stuff came up to complete the dormitories, none came our way. I constructed a cartoon page and gave it to the now-late Madam Dorothy Fraser, our Co-op representative as an act of protest. It was not ignored and the Minister of Co-ops, William Haynes, brought our bunks and mattresses. On the official opening day, we were gathered and Prime Minister Burnham was speaking while we were whispering, then he asked who had done the cartoon about the concentration camp pioneers? I wanted to be somewhere else badly. Eventually, I stood up and he said to me what was weird at the time: “Young man, use your talents to tell the stories of our heroes.”

I had no idea whom he was talking about, or what he meant. I forgot that moment but years later, I developed an interest in my art, inspired by new works that took our interest in the 70s from the international scene and in the local newspaper. By then I had a selection of poetry and had become aware of the worldwide struggles and hard-earned achievements of especially Afro peoples across the planet, especially South Africa and North America. My first poetry book ‘VOYAGE’ supported by artwork was published by curriculum development in 1978, headed by Oswald Kendall. The first illustrated story (comic strip was published in 1981 in the Chronicle, ‘The Shrouded Legacy,’ based on an inherited family encounter with a ‘Masacurraman’ in Bartica). The story was liked by all, but the art wasn’t ready, and I prayed for it to end. I had found a niche, now I had to bring myself to the level of mastering what seemed easy, but unfolding its dimensional compositions set by its competing standards, required tremendous and daunting inputs.

I must mention that the first official I would meet on the road seeking directions after Kuru Kuru was no other than a younger Alan Fenty at the Ministry of Information. This was an angry young man, who mocked my bad spelling, then instructed me that Guyana did not need artists and writers (I’ve heard this story repeated by two other persons). I was very depressed going down the stairs when I heard a “Pssst!” Turning, a lady came to me and told me not to worry with Alan. It was she who directed me to the Queen’s College compound and to Curriculum Development.

It took years for me to understand Fenty’s disillusionment. After the political arson that destroyed ‘Grandma,’ as employment at the Guyana Rice Marketing Board (GRMB) was termed, many of us still etched out immediate work along the nearby waterfront with immediate expenses to meet. I was known as an artist at the GRMB and it was the now-late Hubert Archer, ‘Fat Boy’, the poet from Newtown that with a lot of noise took me to Denis Williams’s office; I had to return with my ad hoc portfolio and he gave me a literary test of diverse questions to be executed immediately. With my art, he recognised that I had done some technical drawing since unlike Rudy Seymour, I had drawn backgrounds with recognisable local architecture. I was employed to be trained by Tyrone Doris in pre-press book layouts and by Dr. Williams as a scientific illustrator (SI) in the field of archaeology, with an allowance that was half of what I was making on the waterfront, and the latter turned out to be my Achilles heel. This however led to a tremendous shaping of understanding contracts and terms with respect to publishing. The first contract was with the Chronicle for ‘Shrouded Legacy.’ Then came the time when I was supposed to go to Scotland to complete the animation component of the S.I. Dr. Williams called me into his office and explained it to me and told me that there was a consensus that I should not be allowed to go because I would not come back. I was disappointed, angry and soon hocked up a freelance arrangement with the GNNL as a commercial artist. I intended to balance both gigs. I was unaware at that time of how many Guyanese had left on overseas scholarships and had not returned, and that the ‘brain drain’ was a tactical weapon in the Cold War era.

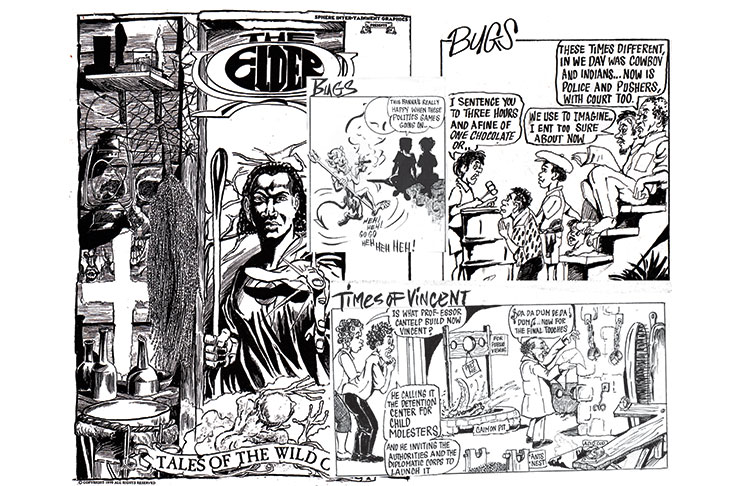

There were things about Guyana that its founder-leader and his support colleagues understood that I was heading towards. At the Chronicle, I was urged by Claudette Earle and Godfrey Wray to create the cartoon strips Bugs and Times of Vincent. They thought that I was too tense and serious, and I did. The strips were great therapy. But then I had found some essential trade books in the discarded Imported ‘Stock Clip Art’ file about syndication of serious and funny strips; the intent to start a business around my work had taken root. I had looked at Rudy Seymour’s work and realised that the preacher was always fighting ‘Big Mama.’ Both my father and Godfather didn’t approve of it: they said that if he didn’t do the colonial thing the rich people wouldn’t publish his comics. True, but Rudy Seymour is still the father of illustrated storytelling in Guyana and he did other commendable work in the field.

Based on an old story, Mrs Pascal had told me I began to write a script and created a character based on the old poetic, mystical stick fighters that existed in creole urban and rural life. The character, ‘The Elder,’ was born. The story was called ‘The Price.. Frank Pilgrim liked it, Adam Harris carried it. Then I was selling ads for the new Stabroek News on the side, when the manager called me to her office and showed me a letter written by a popular Cartoonist family. He was accusing me of teaching ‘occult theory’ with the strip in the Chronicle, The ELDER in The Price. I started defending it. She laughed and said that the letter had nothing to do with that, then she pointed to the bottom of the letter, where it was indicated “Braithwaite should be told that his talents should be used to create comedy.” At the Chronicle, the daily Editor George Baird and I had a similar conversation. His surprising remark was, “These people in the colonial times.” That was surprising, because this man was conservative with his compliments. I had created a physically strong, psychiatrist and mystic, not ideal for an Afro-independent image to exist back then was the lesson I learned.

.jpg)