-warming temperatures and Guyana’s wildlife

ACROSS the rustic savannahs and in the dense rainforest of Guyana, where the skies gleam and towering trees hides some of the world’s most treasured wildlife, climate change—particularly warming temperatures is quietly altering the natural balance.

With a steady rise in temperatures and other erratic weather patterns, the beloved giants of Guyana’s eco-system are struggling to adapt to a rapidly changing habitat.

“For instance, you have cities being destroyed by war, you have habitat disruption in humans and those cause migration, it causes people to move. The same thing happens with wildlife when their habitats are destroyed,” Melanie McTurk a chemist, conservationist and an advocate for community development told the Guyana Chronicle.

Melanie who hails from the Rupununi (Region Nine)—where most of Guyana’s wildlife can be found, noted that there was an increase in temperatures over the past two years. In fact, similar temperatures were felt in the first few months of 2025.

“Last year we were running at about two degrees higher than we are accustomed to seeing. One of the obvious things, and very obvious to habitat loss, [was] fires. We were getting a lot more fires, and the fires that were happening, they were lasting longer, they were destroying greater areas of land, and there were a number of wild species that were injured being caught in those fires.”

According to Guyana’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), between January and May, 91,128 fires were reported.

The EPA said that 5045.45 square miles of land were burned over the course of the five months, with May having the fewest wildfires and March having the most. This is noteworthy not only in absolute terms but also because it makes up six per cent of the 83,000 square miles of the nation’s land area.

While they were mobilisation efforts to protect human life and assets, Melanie said: “We saw a lot more of instances of people encountering animals that were burnt, semi burnt or just had been killed in the fires.”

The Rupununi region recorded fires with the largest magnitude and lifespan since the region is dry, hot, and has lots of dry vegetation (savannahs) which can be seen as fuel.

“The other thing that we started to see is more animals coming out from their regular habitats. Because those habitats were getting hotter, or those habitats had been destroyed, we were seeing more of those animals coming into human spaces, and in some cases, with very negative impacts,” Melanie explained.

Species like tapirs and jaguars were being spotted more.

Unlike us humans, who navigate the seasons with calendars, wildlife takes their cues from their environment.

Take for example, the giant anteater—(Myrmecophaga tridactyla)—an insectivorous mammal native to the Rupununi Savannahs that requires a particular ecological environment.

“They don’t like it to be too hot and they don’t like it to be too cold,” Erin Earl from the South Rupununi Conservation Society (SRCS) explained before noting, “So, they really like a mix, a mosaic of open land, Savannah land and forested areas like That’s their favourite, and that’s what we have in abundance here, especially in the South Rupununi and also in the North Rupununi.”

She added: “So now, if we are extrapolating the environmental impact of climate change, then we can say that species, like giant anteaters particularly, are going to be affected by changes in ambient temperature and also changes in rainfall.”

Another example are Kingfishers–a carnivorous bird often found along the banks of rivers. Erratic weather patterns ranging from extreme flooding to severe dry weather have led to less sightings of the species.

This has been the case for many other species, and according to Melanie, there have been instances where indigenous communities that once welcomed mammals like the Capybara are no longer seeing them.

SO, WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR GUYANA’S WILDLIFE?

Already Guyana’s Hydrometeorological Service (Hydromet) is forecasting above normal weather patterns for both the dry and wet seasons.

In a temperature outlook for February, March and April 2025, above-normal daytime temperatures are expected across all regions throughout this period.

Hydromet noted too that during the night, southern Guyana may experience below-normal temperatures, while the rest of the country is likely to see warmer-than-usual nighttime conditions.

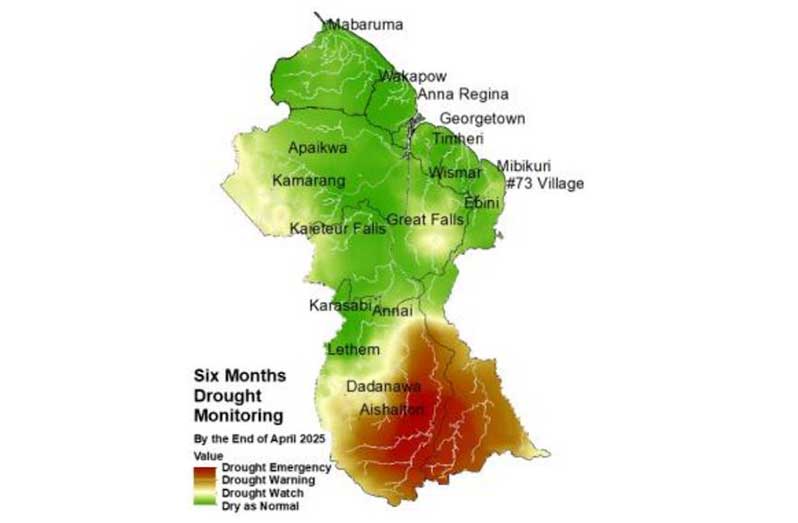

The entity has also warned of ‘Short Term Drought Concern’ by the end of April

2025 and has advised that during this period, reservoirs, rivers, and groundwater sources should be carefully monitored, with measures taken to secure water supplies for domestic, industrial, and agricultural use.

The Rupununi region is forecasted to be the most affected by this.

“We can only try our best to do what we can, but we don’t really have any influence on what’s going to be happening on a large scale in terms of [the] climate, but what we can do is try and reduce these other effects on different species,” Erin said.

LIMITED HUNTING, AGRICULTURE

Despite the mounting concerns, there is still hope for protecting Guyana’s wildlife—if we act wisely.

One of the clearest paths forward is reducing excessive hunting, illegal trading of wild meat and unsustainable agriculture.

These practices of not only destroy habitats but also make it harder for animals to adapt to changing weather patterns.

“Can we reduce or stop the hunting of these animals? Can we protect habitats? And by protecting their habitats, I mean, can we stop or not start any kind of large-scale farming Can we prevent burning in certain places? You know, these kinds of things we can do. Can we protect water courses? Can we ensure that that the right type of food is available, or that we are not taking the food from species that need it?” Erin questioned.

WILDLIFE FARMING

Another option that can be explored to safeguard the country’s biodiversity is the practice of wildlife farming, though a tricky task.

In Guyana’s case the country has already started some efforts to conserve varying species of river turtles that would have been placed under threat due to climate change.

In the past two decades, SRCS has received continual reports from local residents of the South Rupununi noticing a significant decline in the number of river turtles, including the Yellow-spotted River Turtle (Podonemis unifilis).

Between 2021-2023, unseasonal early rainfall caused all the beaches along the Rupununi River to flood which would have resulted in the death of all turtle nests.

Working closely along with indigenous communities, over 2,000 eggs were rescued.

Extremely dry circumstances posed a different challenge to the turtles. Because of the low river levels, hatchlings were either “baked” in their nest or left open to predators. To lessen their susceptibility, the SRCS rangers responded by relocating the hatchlings to deeper pools.

“What we can do is we can, properly, with some species, do some kind of wildlife farming. And that’s what’s we’re trying to do with the river turtles. We’re trying to do with the Capybaras. But it’s very difficult. It’s very tricky.”

(This story was published with the support of the Caribbean Climate Justice Journalism Fellowship, which is a joint venture of Climate Tracker and Open Society Foundations)

.jpg)