By Tota Mangar

MAY 5th 2022 commemorates the 184th anniversary of the arrival of East Indian indentured immigrants in Guyana, the former colony known as British Guiana. Indeed, for over three quarter of a century indentured labourers were imported from the Indian sub-continent to the West Indian colonies, ostensibly to fill the void created by the mass exodus of ex-slaves from the plantations following the abolition of the apprenticeship scheme in 1838.

This influx of East Indian labourers into the Caribbean in the post-Emancipation period of the 19th and early 20th centuries was only one segment of a wider movement to other parts of the world, including places such as Mauritius, Sri Lanka, [formerly Ceylon], Fiji, the Strait Settlements, Natal and other parts of the African continent. As far as Guyana is concerned, the ‘Gladstone Experiment ‘ proved to be the basis of East Indian immigration. John Gladstone, the father of the liberal British statesman, William Ewart Gladstone, was the proprietor of West Demerara plantations, Vreed-en-Hoop and Vreed-en-Stein at precisely the time when the British Guianese planters were beginning to experience labour shortage as a consequence of the withdrawal of ex-slaves or apprentices from plantation labour.

It was in this initial period of ‘crisis change and experimentation’ in the late 1830s that John Gladstone envisaged social and economic advantages in a scheme of East Indian indentured labourers. On this matter, the initiator of East Indian immigration wrote, “a moderate number of Bengalese might be suitable for our purpose.” To this end, he made contact with the Calcutta recruiting firm, Gillanders, Arbuthnot and Company, inquiring about the possibility of obtaining Indian immigrants for his two estates. The firm’s prompt reply was that it envisaged no recruiting problems as Indian labour was already in usage overseas, as for example, in another British colony, Mauritius and moreso “the natives being perfectly ignorant of the place they agree to go, or the length of voyage they are undertaking.” This reply obviously set the stage for the fraud, deceit and coercion which were to permeate the entire recruiting system in India throughout the period of indentureship.

Subsequently, Gladstone obtained permission for his scheme from both the Colonial Office and the Board of Control of the East India Company. In relation to the former body, Secretary of State, Lord Glenelg, in acceding to Gladstone’s request, reiterated the necessity of providing a free return passage when the contractual period was over. However, what was seriously lacking in this initial experiment were the necessary safeguards on crucial issues such as overcrowded ships, unwholesome food, the rather lengthy voyage and change of climate and other related matters.

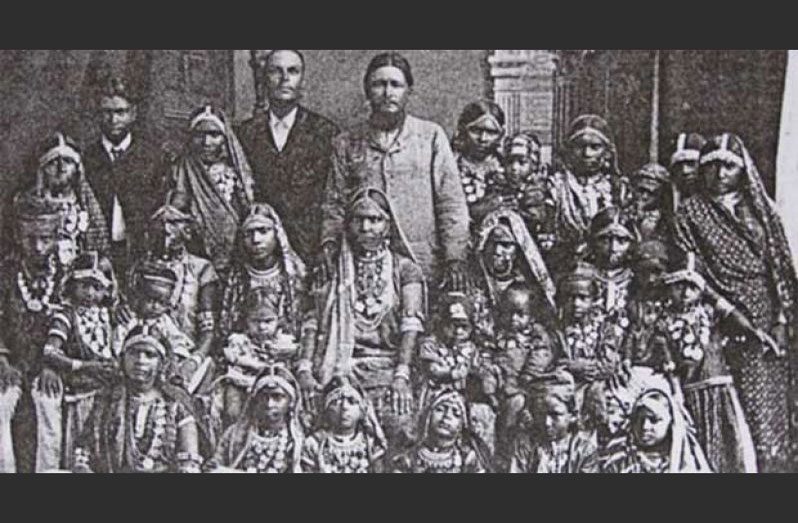

HILL COOLIES

In the final analysis, through the “Gladstone Experiment”, two ships, the SSWhitby and the SS Hesperus departed India with a total of 414 immigrants. This first batch of labourers was referred as “Hill Coolies” mainly because of the areas from where they were acquired specifically, the Chota Nagpur and Bankura districts of the Bengal Presidency. Some 396 immigrants survived the long, arduous crossing and on their arrival in May 1838 they were distributed not only to Gladstone’s two West Demerara estates and Belle View, West Bank Demerara but also to far-flung ones such as Highbury and Waterloo, East Bank Berbice and Anna Regina on the Essequibo Coast.

These first arrivals were on a five-year contract of industrial residence and were described by leading colonial officials of the time as “conservative, docile, simple and able-bodied…” A labour force with such characteristics was quite naturally sine qua non to the survival and prosperity of the plantocracy and the sugar industry in general.

Exposed to the plantations soon after their arrival in the then colony of British Guiana, these newcomers quickly experienced several problems. There were numerous complaints of intimidation, assault and gross negligence on the part of the powerful and very arrogant planters. The mortality rate was quite alarming and many immigrants fell victims to malaria, dysentery and other tropical diseases. As a matter of fact, within the first eighteen months of the scheme, sixty-seven deaths were recorded. The then Governor, Henry Light, even criticised the disproportion of the sexes with a paucity of the sexes. At the end of the five-year stint 236 indentured labourers opted to return to India.

TEMPORARY SUSPENSION

Of significance also, was the temporary suspension of the scheme largely through the active role of the Anti-Slavery Society and its hardworking Secretary, John Scoble, in publicising the grave injustices meted out to the immigrants. Scoble, for his part, visited the colony and verified instances of ill-treatment and other abuses within the system. He advocated “truth, mercy and justice” where the scheme was concerned.

With the implementation of the Government of India Act in 1844, the subsequent approval of a 500,000 pounds loan for future investments in immigration and a worsening of the labour problem in the colony, East Indian immigration to Guyana resumed in 1845. Large-scale importation commenced around the mid-nineteenth century and was to continue virtually uninterrupted until its termination in 1917.

Despite its numerous problems, the first batch involving the ” Gladstone Experiment’ had paved the way for a total of 239,909 East Indian indentured labourers to come to Guyana. Of this figure 75,547 were repatriated to the land of their birth. The remainder who survived the system chose to remain here and to adopt this country as their homeland.

Certainly, our first batch of forefathers who came to Guyana through the “Gladstone Experiment” has been inspirational through their supreme sacrifice, grit and determination in the furtherance of national development and progress. They toiled unceasingly to ensure the survival of the sugar industry. Their successors and their descendants continued in the same vein and have contributed and continue to contribute to almost every sphere of activity including economic, social, cultural, religious and political fields.

We ought to take pride in their sterling contribution. In these trying times of a pandemic, global tension and climate change, let us commit our lives to ensure greater tolerance, mutual understanding, respect and social and economic justice prevail in this dear land of ours. Let us give true meaning to our “One Guyana” initiative and our motto of “One People, One Nation, One Destiny”. The pioneering batch and our foreparents in general would have settled for no less. A Happy 184th Arrival Day Anniversary to All.

.jpg)