By Vanessa Cort

VICE-CHANCELLOR of the University of the West Indies (UWI), Sir Hilary Beckles, has said that poor diet and collective stress are responsible for the high incidence of diabetes and hypertension among Afro-Caribbean people.

Also Chairman of the CARICOM Reparations Commission, Sir Hilary’s sentiments were echoed by Jamaicans who took to the streets to protest the recent visit of British Royals, Prince William and his wife, Kate, who also visited Belize and The Bahamas

Collective stress has been described this way, “By collective stress we think of stress as a cultural artefact (Fineman 1995), that results when members of a particular organisational culture as a group perceive a certain event as stressful”.

The Vice-Chancellor was particularly referring to the ‘institution’ of slavery and the legacy of colonialism which have spawned the kind of unhealthy eating leading to these diseases.

He pointed to the heavily salted meat and sugar in the food given to slaves and the 300 years of exploitation suffered by Black people in the Caribbean at the hands of the British.

This has led to what he termed an “explosion of chronic diseases” and resulted in Black people in this region being the unhealthiest on the planet, with sixty per cent of the people over 60 years old being hypertensive or diabetic or both.

Sir Hilary stated that hard labour, separation from children and the “stress profile endured by slaves” have been ultimately responsible for high blood pressure and diabetes in Black people, asserting “it was the same then as it is now”.

The drugs for these conditions were tested on Caucasian people and are therefore more effective on them.

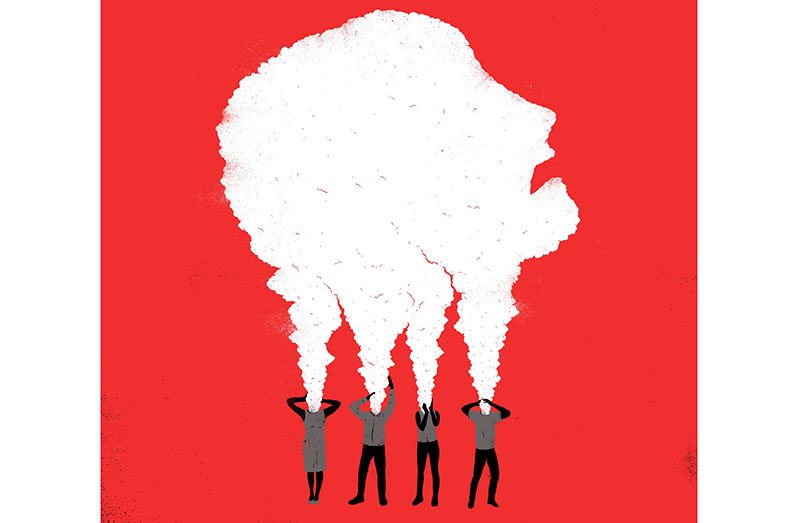

“Something happened to us,” Sir Hilary declared, citing our experience of the stress of slavery which, although in the past, “we are yet in the Jetstream of it”.

The Vice-Chancellor has been making the argument for special drugs to treat these diseases in Caribbean people for several years now,

Pharmaceutical companies are unwilling to undertake the research claiming that the small percentage of overall cases does not warrant the expenditure necessary for the research.

And if these diseases are the physical manifestation of the devastating effect of slavery and the colonial era, how great must be the psychological toll?

The trauma of being captured, transported under shocking conditions, enslaved – with all its myriad repercussions – and robbed of identity has surely left an indelible mark on our collective psyche.

So while the term ‘collective stress’ has most often been used in reference to groups within organisations, it has been acknowledged as having a much wider scope.

A Disaster Research Centre (DRC) article dealing with ‘Conceptualising Collective Stress’ and examining disaster as a stressor stated “This conceptualisation, however, is capable of being extended to other types of collective stress induced by different agents.”

And one particularly telling reason advanced for the cause of collective trauma is “a cataclysmic event”. Another states that “Collective trauma also occurs because of ongoing collective physical and emotional injury due to a repeated exposure to race-based stress”.

Certainly, the notion of collective stress warrants a closer look, particularly as it applies to slavery and the colonial and post-colonial era.

.jpg)