THE limited literature on the aforesaid title during the period under discussion suggests that when indenture immigration ceased from India in 1917, so did Indian migration in British Guiana. This characterisation is a misnomer. Indians were not non-migratory people but quite on the contrary showing myriad migration dynamics that have unfortunately escaped analyses.

The mere thought that Indians had travelled thousands of miles to labour in foreign colonies would imply that they would continue this movement looking for better livelihood opportunities. Their indentured contract obligation did not pin them down to a specific spot in a specific colony as narrated elsewhere. Migration is rarely one-dimensional. Some indentured Indians were trans-migratory for over 15 years, spending five years in British Guiana, five years in Mauritius and another five years in Natal, South Africa, for example.

Moreover, the repatriation of Indians continued until 1955, private migration from India continued after 1920, migration from the estates to rural settlement and urban areas and within the Caribbean and even to Great Britain increased exponentially after 1920.

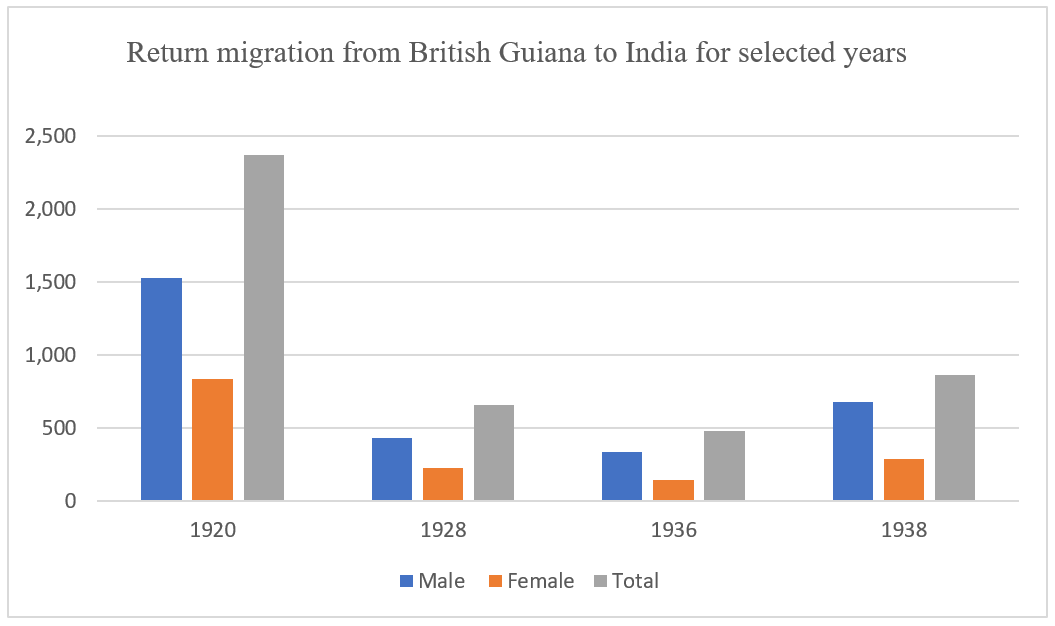

The focus here is on the return of Indians from British Guiana to India and the arrival of Indians to British Guiana between 1920-1940, a rather so-called quiet period of Indians in British Guiana when compared with other periods. I label this movement as crisscrossed, meaning some Indians were leaving and entering British Guiana at the same time. I start by showing the return migration of Indians from British Guiana to India in graph one, according to British Guiana Immigration Agent-General report for the years 1920, 1928, 1936, and 1938.

The graph shows, for example, for 1920, of a total of about 2,275, some 1,500 males and 750 females left British Guiana. Indian female migration was always lower than male migration. The indenture system favoured young Indian males, believing that Indian females would be a burden to plantation work routine because of child-bearing and rearing responsibilities, Sigh! Indian females were reluctant to travel on their own, fearing the lack of safety from the patriarchal system and breaking of customary caste rules. The total figure of returnees dropped as time wore on toward the 1940s and 1950s. Indians had become to see British Guiana as their home, which stymied out-migration.

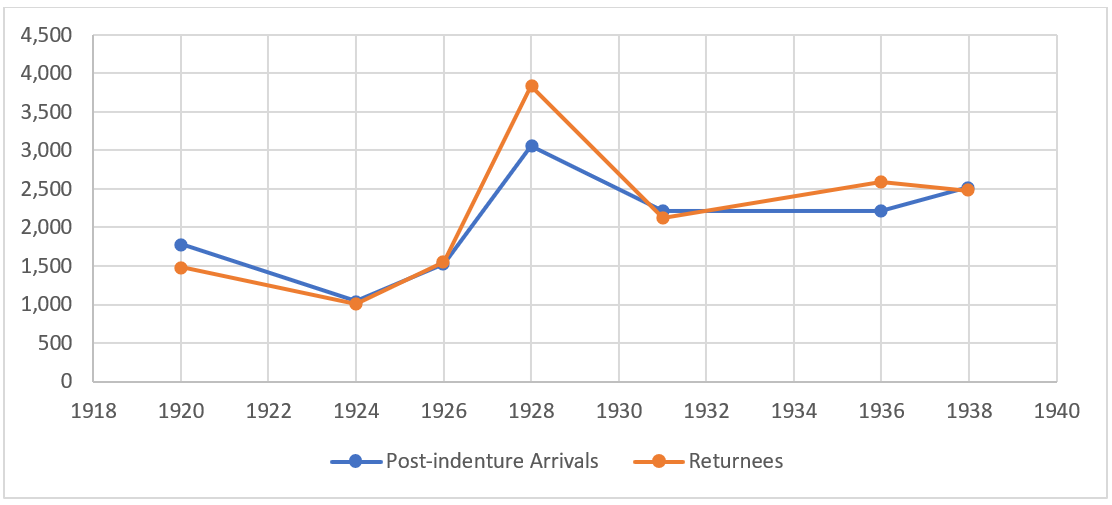

Paralleling this return migration was an influx of Indians who arrived in British Guiana on ordinary ships after the abolition of indenture, which was sometimes equal to the number of returnees. For instance, in 1924, 1926, 1931, and 1938 in graph two, the returnees and arrivals were identical in numbers, according to British Guiana Immigration Agent General report for those years.

The figures in the early-post indenture or independent movement from India to British Guiana raise a fundamental question to the whole narrative of Indian indenture as being a new system of slavery. Why would these Indians want to go to British Guiana, return to India, and come back for a second time on their own accord, paying their own passage, if the indenture system were semi-slavery? One can only surmise that India was worse than British Guiana as far as labour relations are concerned. We do not know how many women arrived during this early post-indenture migration period. It is likely that about 25 per cent of them were women.

We do have, however, an idea of how much savings post-indenture and returning Indians accumulated. To clarify, the post-indenture Indians were those Indians who were in the colonies for some time and not the ones who arrived from India after indenture was abolished. In 1928, the Post Office Saving Bank shows that there were 34,836 depositors of all races in British Guiana. Of this figure 9,443 were Indians. The total amount of money deposited was $1,836,650,78, an average of $52.72 for all races.

Indians deposited $913,778,79, an average of $96.76 per depositor, according to the Immigration Agent General report of 1929. It is noteworthy that not all Indians deposited their money in the banks but rather stashed their savings in mattresses and in tree holes, implying that the bank deposits were not an accurate reflection of Indians’ savings. Interestingly, too, is that stories have been told that some Indians would deposit their savings in banks and then would go back within a few weeks and withdraw some savings to ensure that they were there, according to the trove of Indian oral village sources and traditions.

What the above statistics reveal is that Indians were not the majority depositors of savings in the colonial bank but the amount of money they deposited surpassed all races; a pattern they have supposedly continued to practise in the modern period. What is also interesting is that in 1933 and 1934, 520 and 503 Wills were made by Indians, indicating that they had accumulated some savings and property, according to the Immigration Agent General report of 1934 and 1935.

The challenge here, however, is to determine how much of these savings stayed in British Guiana or were remitted to India. The record shows that in 1928, the sum of $10,311,46 was remitted to India, a marginal figure when compared to $913,778,79 that stayed in the colonial bank as revealed by Immigration Agent General report of 1929.

HAPPY INDIAN ARRIVAL DAY!

(lomarsh.roopnarine@jsums.edu).

.jpg)