WHEN Indian indenture ended in British Guiana in 1920, an estimated 239,909 Indians were brought to the colony. Of this total, an estimated 75,000 went back to India when their contracts expired. We are not sure how many Indians returned to British Guiana for a second time under contract, one blind spot in the Indian indentured experience in Demra/Demerara/British Guiana. However, if a conservative estimate is conducted, based on the reports of the Immigration Agent (recorder of indentured events) that about 100 of them returned to British Guiana each year for the period over 60 years, then it is probable that an estimated 5,000 to 6,000 returned for the second time. The return migration to British Guiana refers to Indians who had served indenture and then returned to India, but decided to indenture themselves to the same colony.

Now, it was not automatic to indenture for a second time. The immigration system screened second-time migrants, based on their state of mind, physical fitness, age, as well as how well the indentured Indian had performed in the colony, including a record of obedience to plantation routine expectations of confirmation to work regulations and rules. This procedure was different from the first migration, when practically anyone could indenture to fill the ships before departure, hence, we have stories of duping, kidnapping (yeah, some kids were indeed napping), and so on, to serve indenture.

Many intended second-time indentured Indians did not make it through the immigration gates. They, however, hung around the immigration depots, using whatever tactics to beat the immigration procedures to get them to British Guiana and elsewhere. Some were successful, while others hung around the depots for years rather than returning to their caste-structured villages. They feared poor treatment and expulsion for breaking caste rules. Out-migration violated caste rules.

What is also perplexing is that at least 1000 Indians paid their own passage from India to British Guiana each year, from 1920 to 1930, demonstrating that at least 10,000 came to British Guiana on their own terms. These Indians were not under contract, because they arrived following the abolishment of indenture, but they worked in the sugar industry. In my years of studying indenture, this movement confuses the daylights out of me, on the basis as to why would these individuals want to pay their own passage to work in a labour system dubbed as monstrous. Oh, no, I am defending the imperial indenture system; I am raising questions about the neo-slave narrative, or scholarship of indenture.

Using random ship and plantation records, of the 239,909 brought to British Guiana, an estimated 10 per cent died on the sea voyage and on the plantations, while about the same figure was born on the sea voyage and in British Guiana during the 80 years of indenture, from 1838 to 1920. This would mean that about 20,000 died, while 20,000 were born. What should be clarified is that at no time during indenture the Indian population was 239,909. Instead, this figure was the total number of Indians brought during a period of 80 years. An estimated 3,000 were brought to British Guiana each year during indenture, although, in some years, immigration was higher than others. The Indian population during indenture in British Guiana was no less than 100,000, particularly by the 1900s, out of a total population of 250,000. What is also accurate is that the Indian population grew steadily, even when immigration ceased in 1917. Table One shows growth of the Indian population between 1920 and 1930.

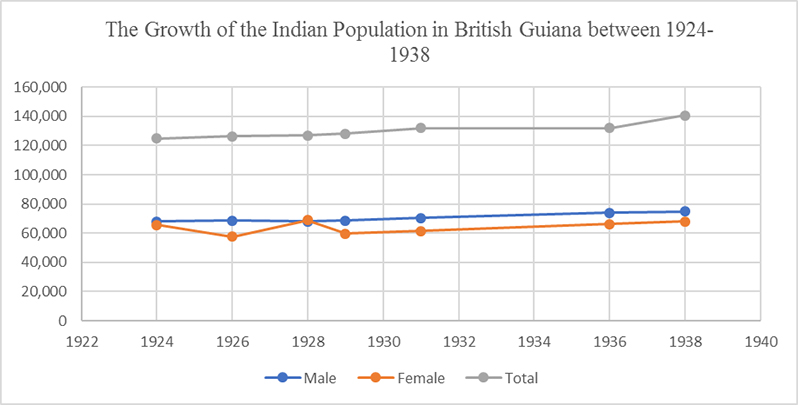

Figure 1. Showing the growth of the Indian Population in British Guiana between 1924-1938

Three analyses can be made from the aforesaid table. First, there was a steady increase of the Indian population, which was largely due to fewer deaths, and more births. For example, in 1924, out of a population of 129,817, there were 4,317 births and 3,459 deaths, a difference of 858 births, according to the Immigration Agent General of 1925. This figure suggests that living and working conditions had improved in Indian communities, brought about by better access to western healthcare as Indians decided to settle in the colony. Second, the sex disparity between males and females was reduced substantially. During indenture, the sex ratio was 25 females to every 100 males.

By contrast, in 1929, the sex ratio for adult female to male was 82 to 100, while for children, it was 91 females to 100 males, and the average among adults and children was 85 females to 100 males, according to the report of the Immigration Agent General of 1930. This remarkable equalisation of the sexes was as a result of natural increase, as well as different lifestyles. Indian men have always lived shorter lives than Indian women in British Guiana, because men were exposed to the harsher side of plantation life that included hard work and the consumption of alcohol. Third, as the overall population grew and the sex disparity reduced in the Indian population, marriages increased steadily. For example, 343, 391, 482, 535, 609 marriages were recorded for the years 1926, 1927, 1930, 1937 and 1938, respectively, according to the Immigration Agent General’s report from 1927 to 1939 (lomarsh.roopnarine@jsums.edu).