— as local measures ‘mask’ communities from deadly virus

IT is just after the crack of dawn on Monday morning. Dorothy James, an elderly guest house proprietor in the indigenous community of Aishalton, is busy preparing breakfast. For her guests, she prepares a jug of juice using fresh oranges that she grew in her garden.

In the background, just before the six o’clock news airs, a radio drama on COVID-19 plays on James’ solar-powered radio. The drama encourages persons to wear their face masks, constantly wash their hands and maintain an appropriate social distance to safeguard against contracting the novel coronavirus.

Aishalton is located in the ‘Deep South’ area of the Rupununi, located in Region Nine (Upper Takutu-Upper Essequibo). It is one of the 21 communities located in the Wapichan territory.

And in Aishalton, and the Deep South Rupununi at large, the residents are cognisant of the measures needed to safeguard against contracting the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes the disease, COVID-19. It is the adherence to these measures that, perhaps, prevented the area from recording a single case of COVID-19 in the year since the virus has spread to Guyana.

“For us in the village we acted quickly when the pandemic first came to Guyana. What we did first, on the 28th of March, was that we erected a gate quickly,” Michael Thomas, the Toshao of Aishalton, told this publication in a recent interview.

This gate was erected at the entrance to the community to monitor and record travel into and out of Aishalton, allowing the village council to engage in its own contact tracing, if need be. They, gate monitors — which are women from the village — are tasked with recording the names and temperature of each person.

According to Toshao Thomas, it was also important to institute such a system since there is frequent travel through the community, from local miners and those from nearby Brazil, heading into the gold mining area of Marudi. This would later present greater concerns.

These miners would often stop in the village to purchase food or stay overnight at one of the guesthouses, but due to concerns over the spread of the coronavirus, the village council prohibited interaction between the miners and the villagers.

Beyond just erecting the gate, though, Thomas and other Toshaos across the Wapichan territory decided that a coordinated approach to mitigating the effects of the pandemic was necessary.

These toshaos form part of the South Rupununi District Council (SRDC), a body that aids in the management of the Wapichan territory. And in the wake of the emergent COVID-19 pandemic, the council, along with health officials in the communities, convened a meeting to chart a way forward.

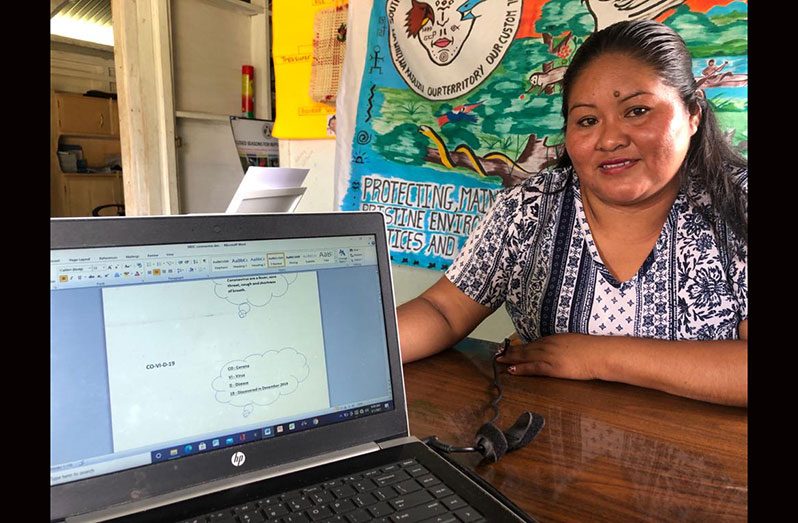

“SRDC visited all the communities right away to hold meetings to host awareness sessions, to demonstrate how to wash hands and so,” Public Relations Officer (PRO) of the SRDC, Immaculata Casimero, told this newspaper.

LARGE GATHERINGS PROHIBITED

Additionally, Casimero highlighted that all large gatherings were subsequently prohibited; gates similar to the one at Aishalton were erected at the entrance of all the communities. Travel to Lethem for goods and supplies was only permitted twice weekly. The SRDC also organised sanitisation and food supplies for villagers.

“We did a lot of awareness sessions,” the PRO said also. “We did videos… we even translated them from English into Wapichan so that our people could understand what this virus is about.”

These messages were simple, condensing the scientific terms into easily understood messages. And they were aired on the radio. The SRDC also acquired loud speakers and played the audio in some communities, while flash drives were procured to distribute the messages to others. These helped to circumvent the challenges of getting reliable information due to limited, or sometimes non-existent, Internet connectivity and the absence of easily accessible health officials.

Toshao Thomas was particularly pleased with the proactive measures instituted and how well the villagers adhered to those. “All other districts recorded cases but Deep South maintained a safe environment,” Toshao Thomas said, proudly.

LOCAL LEADERSHIP

Toshao Thomas also opined that the groundswell of support, across the Wapichan territory, for the measures was garnered because the sources of the measures were the local Council and community leaders.

“I’ve been to Aishalton and I love the system. It’s all because of leadership,” Bertie Xavier, the Vice-Chairman of Region Nine, told this newspaper.

Xavier highlighted that local leaders, across the region, strategically coordinated efforts to protect the people.

In Rewa, a riverain community in the North Rupununi, the village council restricted unauthorised travel into the community by placing a rope — with intermittent gas containers attached to it — across the waterway. This stymied efforts to bypass the checkpoint and sneak into the community. And Rewa has not recorded any COVID-19 cases, either.

“Every village had its own way of managing the situation,” Xavier contended. He, however, reasoned that the geography and location of the far-flung communities also contributed.

While Deep South has not recorded any positive COVID-19 cases, there have been cases recorded in the South Central and North Rupununi areas. In Xavier’s village of Wowetta, in the north, for example, there was an outbreak of COVID-19 last August and Xavier was among one of the 70 persons infected with the coronavirus.

This village is located on the public road, where vehicles making the 16-hour journey from Georgetown to Lethem, or vice-versa, traverse daily, several times a day. Since Wowetta is not as secluded as Aishalton, for example, the virus was easily spread by persons travelling along the Georgetown route.

BRAZIL CONCERNS

There is a wider concern over the spread of the coronavirus, also.

The Deep South, and all of Region Nine, by extension, share an intimate relationship with the Roraima State of Brazil. There is an official border crossing between the two countries; this is the Takutu Bridge, which is located in Lethem, Region’s Nine capital town and the region’s commercial hub.

Mayor of Lethem, John Macedo told this newspaper that prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Lethem attracted about 20,000 persons from Brazil, daily. These were not all Brazilian nationals; many were Guyanese who have established themselves on both sides of the border. Still, considering that the population of Guyana is approximately 750,000 persons, that is a sizable quota of travellers.

As the pandemic progressed, concerns over the number of travellers from Brazil increased due to the outbreak of COVID-19 in that country. The local authorities closed the Takutu Bridge and only permitted the trade of goods on Thursday. That provided limited relief, however.

“The border is porous stretching from Karasabai all the way to Deep South. It’s just porous and we don’t have the capacity to control it. Even if you place soldiers at the border, they’d just be at one point.

“It’s a very hard situation to deal with because every single day, even though the border is closed, you have these persons coming over very early in the morning… It’s almost every location you go to, there is a fine border crossing,” the Vice-Chairman said.

Illegal crossings across the border occur on what has been termed “backtrack” routes. There is one such route close to Aishalton.

Though Aishalton is nestled away in the Deep South area, taking the back track route from Brazil allows persons to come over with great ease and travel through Aishalton to get to the Marudi mines.

“Marudi is not far from us (in Aishalton) and we’re very fearful of the mining because in the mining there’s no proper measures put in place in the mining areas and they don’t follow no (sic) national COVID-19 guidelines and if they have a case they can spread it into our communities,” Casimero lamented.

Beyond just the importation of the virus, there are now concerns over the importation of variants of the virus — specifically the P1 and P2 variants that have emerged in Brazil.

According to the Minister of Health, Dr. Frank Anthony, these variants of the coronavirus are more transmissible; this means that they can be transmitted from person-to-person more readily, potentially resulting in an overall increase of cases.

According to Professor of Molecular Genetics and Virology at the University of the West Indies (UWI), St. Augustine Campus, Christine Carrington, the variants arose through accumulation of mutations (genetic changes) that can occur when viruses replicate within the cells of infected individuals.

And, she told the Guyana Chronicle the vast majority of mutations are inconsequential but occasionally mutations arise that can give the virus a “fitness advantage”.

These include increased transmissibility in the P1 Brazil variant and the B.1.1.7 United Kingdom variant, and in the case of B.1.351 South Africa variant and P1, ability to partially escape from protective immune responses produced by current COVID-19 vaccines.

Although, thankfully, all of the vaccines can still prevent variants causing severe illness, hospitalisation and death. Research on whether these variants lead to more severe or life-threatening infections is ongoing.

Professor Carrington explained, however, that the public health interventions adopted during the pandemic, that is, wearing masks, social distancing, border restrictions, inter alia, would help to prevent the importation and spread of variants.

“There is also a growing body of evidence that (in addition to protecting against disease), COVID-19 vaccines reduce person-to-person transmission, so vaccines can also play an important role in this regard,” Professor Carrington highlighted.

EQUITABLE DISTRIBUTION?

But the distribution of vaccines presents yet another cause for concern for persons in the Deep South. Given the geography of Region Nine and the far-flung locations of many communities, the COVID-19 vaccination rollout here is confronted by logistical challenges.

On February 12, Guyana began its rollout of the COVID-19 vaccines following the donation of 3,000 doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines from Barbados. As per the national vaccination schedule, frontline health workers have been given the vaccine first.

Devin Sanasie, the Medex attached to the Aishalton District hospital, was one of four persons who received vaccines from that first tranche. He and his three colleagues, however, had to travel to Lethem to receive these vaccines.

Leaving the safety of COVID-free Aishalton and travelling to the North, where there has been a majority of the region’s COVID-19 cases, raised concerns from the health workers in the Deep South community.

Addressing these concerns, the Health Minister explained that since the country only had a small quantity of vaccines at the time, it was more feasible to ask the health workers to travel to the central distribution point (Lethem) instead of taking just four vaccines to Aishalton. He, however, assured that once Guyana secured more vaccines, there would be a broader distribution system.

“In some cases we would be able to take the vaccines to the communities, in others we would advise them to come to a central point where they would be vaccinated. It depends on the strategy,” the Health Minister related.

Though health centres and district hospitals across this region, and other hinterland regions, are not equipped with the cold storage requirements for the COVID-19 vaccines, Dr. Anthony said that ice-boxes will be used to transport the vaccines into communities.

The use of ice-boxes to transport vaccines is a common practice, according to Dr. Anthony, who also noted that this is done with the distribution of many of the childhood vaccines.

Meanwhile, Toshao Thomas related that he and his villagers expect more information from the local health authorities on the COVID-19 vaccines before the mass rollout.

Similarly, the SRDC PRO emphasised, “I would like to see more information filtered into the communities and not just kept on the coast and use our organisations.”

“I would encourage the Government to use our local organisations and use our village councils to get these messages out to people. I think working together as partners, we can do more good work than just the Government doing its own work and communities doing its own work,” Casimero underscored.

This story was written & produced as part of a media skills development programme delivered by Thomson Reuters Foundation and in partnership with the Sabin Vaccine Institute. The content is the sole responsibility of the author and the publisher.

.png)