If you do, it will prevent ‘eye-pass’ Part 3

THE lie is a potent weapon; it will reshape your image of reality in the mirror, as well as condition your mind to interpret what you see as not what it is. The lie depends upon us not to be bold enough to question the authenticity of the echo transmitted to our present, or pay interest to the scribes who have left us their opinions, biases, views as witnesses of events long gone, so we may interpret from the past, the present, and have a confident view to illuminating the future.

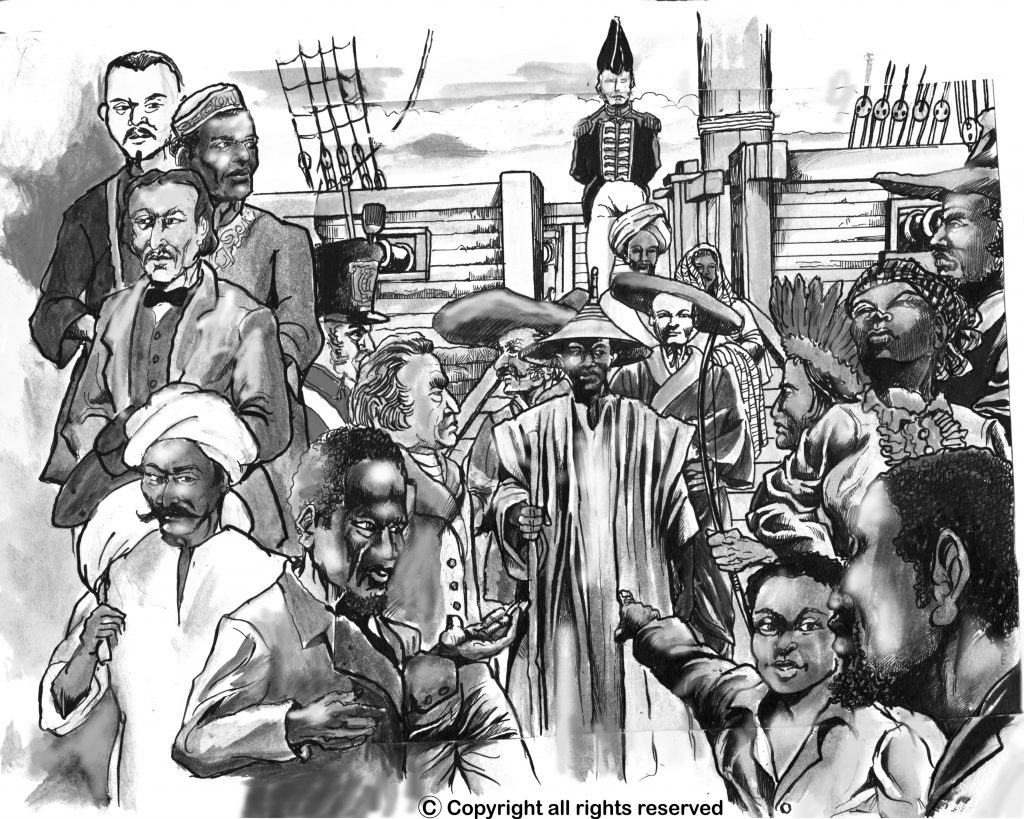

British Guiana, post-Emancipation. A colony, and like all colonies across time, is developed to serve the interests and principle needs of the colonisers. In the timeline of this article, slavery is emancipated, the peak of the society is composed of plantation owners and their merchant kinfolk, and the bottom, the citizen Creole population, the freed enslaved, poor whites and the Amerindians – the latter were not domiciled in the Townships. Then there were the contracted indentured workers viewed as temporary immigrant workers. Those from Africa quickly merged with the Creoles. The only group from that who were of visible contact were the Portuguese. They would soon be integrated into the Creole group. The Chinese were a gradual presence as were the East Indians. Most, however, were located on the estate plantations. All with not enough of a local economy to distribute its wealth to the content of its citizens and those inhabiting its space. In 1884-5 Von Bismarck held a conference in Berlin with other European countries on the invasion and colonisation of Africa; this would entail conflict, resistance, atrocities and mass murder. This was also the age of Charles Darwin, Karl Marx, Francis Galton, Herbert Spencer and the pseudo beliefs of Thomas Malthus father of scientific racism, which would help to justify the new Imperialism in Europe and against Africa with its tremendous wealth. Aspects or nuances of these new ideas would creep into British Guiana to interpret one human variation from the other anew, confounding myths and perceptions even more.

The realisation by the 1880s had dawned upon the Portuguese that though they were used by the plantocracy to disable the Creole business aims, and hopefully drive the Creole back to the plantation (which did fail, with the Afro-Creole rush towards the opening of the ‘Gold Bush’ in the 1880’s). The Portuguese had established themselves and was now disliked by both the disenfranchised Creole and the English merchants who thought that they had done too well. “The Portuguese who had previously borne the contempt of the planters, who never considered them as fellow-whites nor included them in the European social milieu, were now in a position of political equity.” Mary Noel Menezes, R.S.M THE PORTUGUESE OF GUYANA: A STUDY OF CULTURE AND CONFLICT. This had occurred because of a phenomenon of shared grievances that led the Portuguese to forge an alliance with the Afro-Creole middle class, as presented by Kemani S. Nehusi [Francis Drakes] History Gazette August 1989: “ Portuguese entry in large numbers into the formal political process brought the highest level of cohesion achieved in the Guyanese middle class during the decades before 1900.”

However, movement in the interest of the working class had to wait for the intervention of grass root leadership like Hubert Nathaniel Critchlow from 1905 onwards. The East Indians came from conditions, both cultural and economically separate from all the other groups. Judeo/Christian values echoed throughout both African and Europeans which includes the Portuguese, Africans and Amerindians had similar tribal beliefs with differences in some areas. But none equalled the expanses of the caste system. It dictates and impacts on the East Indian community, though many rejected those forms. Some came as Muslim, others as the Madras, however perceptions of self and the other were primarily based on the writings of the sage Vamiki known as the Ramayana and the Mahabharata and the Laws of Manu, though diluted into freedoms, especially for women in the context of 19th ct B.G, influences persisted in the imagination. The 1900s onward were shaped by events at home and abroad still significant today, referred towards the emphasis of a point, but hardly explored. As are the following events: “Joseph Luckhoo was the only East Indian to win a seat. He attended the same school as his brother and studied law in London. In 1912 he was called to the bar. He defeated a European planter, J.B. Laing, whose estate, Marionville in Wakenaam, was situated within the south-west Essequibo constituency. Of the five Indians who contested the elections Luckhoo alone was a member of the Peoples Association. This was a quasi-political party, dominated by African, Portuguese and coloured middle-class elements- Luckhoo’s success came primarily from his affiliation to this body which appealed specifically to the African electorate. He also obtained the Indian votes that were crucial to this doubtful seat” … “ Governor Wilfred Collet (1919-22) also had a sanguine view of Luckhoo’s election. He argued that Luckhoo’s election with African votes proved that East Indians under the present system had considerable influence. Moreover, the fact that an East Indian is elected by a Negro vote does not seem to be conductive of hatred between the two races, but the reverse” Tyrone Ramnarine Guyana Historical Journal Volume 11, 1990.

The confusion that followed was that Joseph Luckhoo, W. Hewley Wharton and Parbhu Sawh petitioned in 1919 the Crown of England to convert British Guyana to an East Indian state through the reopening of Indian indentureship, on the grounds that “No barrier of any kind is erected against Indians in British Guiana-as is the case in Natal South Africa, etc. Here they enjoy equal rights and privileges in the truest sense of the words –on the principles of “Man and Brother.” It proceeds from the colony as a whole represented by its legislature and its various public bodies, municipal and otherwise.” The Luckhoo response to the goodwill of his Creole colleagues has never been understood. Why did he transform a collective agenda to an ethnic mode? Unlike the other Creole population then, that never looked back with longing to their old world the condition of the Indo-mind is explained by Clem Seecharan in India and the shaping of the Indo Guyanese Imagination 1820’s-1920’s: “This solid identity with “Mother India”, however, was accompanied by some negative repercussions for the political development of Indians in British Guiana. It prolonged a sense of ambivalence towards the colony, even among Creolised, Christian Indians. It delayed the emergence of a comprehensive, unmediated loyalty to British Guiana. A vacillating, frequently petty, leadership survived well into the 1940’s: they seemed to be perpetually looking over their shoulders for “Mother India’s” guidance and reassurance. Above all, it encouraged the Indo Guyanese to ignore the feelings of the Afro-Guyanese, and the political, economic and cultural space this group was also demanding.” This was however encouraged by India.

Afro Guyanese response to this is briefly captured by a rare publication, a biography of Andrew Benjamin Brown of Den Amstel by his wife Mrs. Edith Brown. Mr Brown was a selected member of the Legislature who had proposed a compromise that for every 100 Indians brought in 50 Africans be so immigrated, he had done much of the structure for this, but it was defeated. The Indian Government did not sanction Immigration, but India, now an Independent Republic within the commonwealth, maintains contact with the Indians here through a Commissioner of India who resides in Trinidad. The main contention that Afro-Guyanese had at the time is captured in the following of Mr Brown’s meeting at the Rattray Memorial Congregational Church at Bagotville, WBD “ urging that the people meaning, of course, those of African descent, couldn’t get work and were already starving, and now Mr Brown, their representative was joining with the planters to bring in more labourers, which would make their condition worse.”

They were against the process of the immigration of any more workers despite race on the grounds of the state of the colony, that was deplorable to their existence (so much for the good old days of the 1920s).

This concludes our brief History perspective of the post-emancipation era.

.jpg)