THE Constitution should not be interpreted in a narrow and legalistic way, Attorney General Basil Williams said in his response to a case brought against him by political commentator, Christopher Ram, who wants the High Court to rule that the no-confidence motion was validly passed.

In his submissions to the High Court, Attorney-at-Law Kamal Ramkarran, on behalf of his client Christopher Ram, cited several principles of constitutional and statutory interpretation, including reference to Articles 1 and 9 of the Constitution.

Article I provides that “Guyana is an indivisible, secular, democratic, sovereign state in the course of transition from capitalism to socialism and shall be known as the Co-operative Republic of Guyana,” while Article 9 provides that “Sovereignty belongs to the people, who exercise it through their representatives and the democratic organs established by or under this Constitution.”

Ramkarran, in laying the basis of his argument, alluded to the case of the Attorney General of Guyana v Richardson (2018) in which Justice Adrian Saunders stated that the sovereignty of the people of Guyana is exercised through their representatives and democratic organs established by the Constitution.

“When, therefore, the people exercised that sovereignty through their representatives, who voted in favour of the passage of the motion on 21 December 2018, because Guyana is a democratic state, the consequence of that vote was that elections must be held within three months, although elections were not then due,” Ramkarran said in his written submissions to the court.

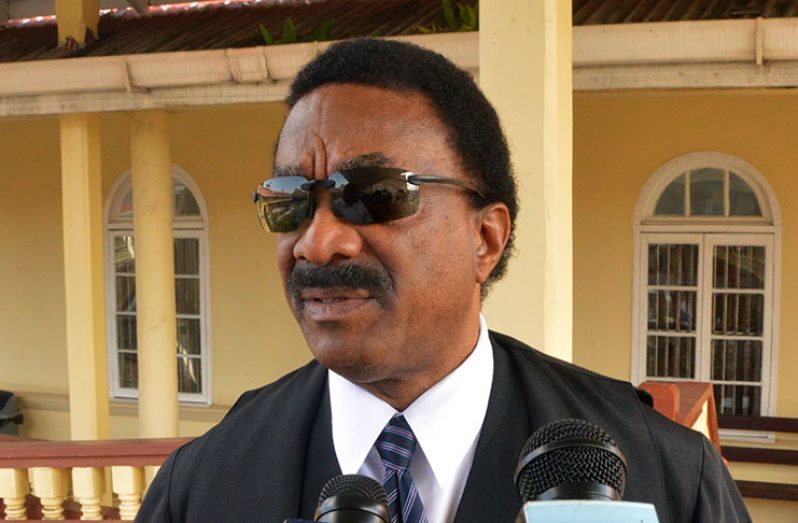

But Attorney-at-Law Maxwell Edwards, who is representing the Attorney General, in his response said Articles 1 and 9 are not relevant to the interpretation and application of the vote required for the passing of the motion upon a vote of confidence as outlined in Article 106 (6). He argued that the Constitution should not be interpreted in such narrow fashion.

“The Constitution of Guyana is a written Constitution as distinct from the unwritten constitutions and, as such, the language of the Constitution should not be construed in a narrow and legalistic way, but broadly and purposively, so as to give effect to the spirit of the provisions and to avoid what has been called ‘the austerity of tabulated legalism,” Edwards told the Court.

Ramkarran, in his written submissions, argued that Articles 106 (6) and 106 (7) clearly state that the Cabinet, including the President, should resign and elections held within 90 days. But government, he said, has declined to give effect to the provisions.

But Edwards, in his rebuttal, said Ram has completely misconstrued the requirement of Article 106 (7) which clarifies that the resignation is contingent upon the dissolution of Parliament before the holding of General and Regional Elections. It was pointed out that Article 106 (7) states that the government shall resign “after the President takes the oath of office following the election.”

“The First Named Respondent rejects the contention of a caretaker government as alleged by the Applicant in his Submissions. It is submitted that the Resolution of Parliament upon which the Applicant relies was not validly passed by an absolute majority of all the elected members within the meaning of Article 106 (6) so as to constitute a valid defeat of the government upon a vote of confidence,” Edwards argued.

In Ram’s view, a majority as regards the Constitution (Article 106 (6) simply means one more vote that the votes of the opposing voters. In the context of the entire Constitution, he, through his Attorney, is arguing that the phrase ‘the vote of a majority of all the elected members of the National Assembly’ means a majority of the votes of the members present and voting. This, he posited, is also just one more vote than the votes of the opposing voters. “In both instances, that number is 33 votes,” Ramkarran argued on behalf of his client.

But Edwards said the argument put by Ramkarran is “untenable,” contending that Ram fell into error by predicating his on the contention that Article 106 (6) required a simple majority.

“The Applicant did not address the question of an absolute majority or a majority of higher than a simple majority in light of the grave consequences and implications of a successful vote on a No-Confidence Motion,” Edwards argued.

He said it is Article 168 (1) which requires a majority of ‘members present and voting’ that speaks to a simple majority.

On the issue of dual citizenship, which is the subject of dispute in another constitutional matter regarding the validity of the December 21, 2018 Vote of No-Confidence, Edwards submitted that the vote cast by then Parliamentarian Charrandass Persaud is invalid on the basis that he is a dual citizen. The constitution bars Members of Parliament from holding dual citizenship.

“It would be calamitous for our democracy if otherwise lawful proceedings of Parliament could be invalidated simply by having a malevolent actor worm his way into the Assembly and participate when he is not authorized to. It would be equally calamitous for our democracy if such a person were able to reap rewards of his malevolent action by sabotaging the will of those persons lawfully participating in Parliamentary proceedings,” Edwards said.

Oral submissions, in this case, will be heard on Wednesday in the High Court before Chief Justice (ag) Roxane George-Wiltshire.

.jpg)