The 18th Century Venetian’s name is synonymous with sexual adventure. But Casanova’s

renowned writings reveal a more complex character, writes Hephzibah Anderson.

(BBC) Casanova is code for cad, rake and roué. A ‘Casanova’ is the consummate pick-up artist, a sexual adventurer of the type who was swiping right, metaphorically speaking at least, long before your mobile phone became a singles’ bar. Above all, a Casanova is not to be believed – he’s the kind of guy who’ll say anything to get a girl into bed (and yes, he calls women ‘girls’ – either that or ‘ladies’, with a lothario’s leering emphasis on the first syllable).

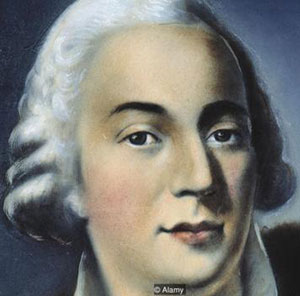

It’s little wonder, then, that we tend to forget Casanova was a real person who wined, dined and bedded his way around 18th-Century Europe, retiring to write about his exploits in X-rated detail. But that’s only half the story. The myth that gave birth to the noun, it turns out, isn’t really his creation at all. Moreover, the legacy that he can truly claim as his own is at once less titillating and markedly more fascinating, speaking directly to the heart of how we tell the stories of our own lives and loves in the 21st Century.

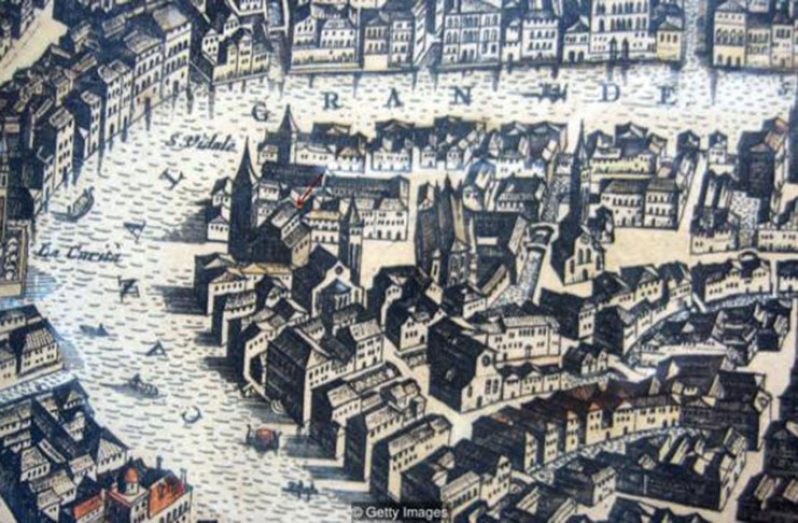

Giacomo Girolamo Casanova was born in Venice in 1725, back when the city was a hotbed of vice, famed for its gambling, its courtesans and its carnival. There’s a reason it was such an essential stop for well-to-do youths set loose on their Grand Tours, and it didn’t have much to do with St Mark’s Basilica.

Casanova’s parents were lowly theatre folk, and at nine, he was sent away from the island to

Padua, where he lived with his tutor, whose daughter was responsible for Casanova’s first erotic experience. No slouch, he graduated from the University of Padua at 17 with a law degree, having also studied chemistry, maths and medicine, as well as moral philosophy and, informally though no less assiduously, gambling.

A rake’s progess

Returning to Venice, he took holy orders and lost his virginity – to two sisters of the non-religious kind. The gambling continued and mounting debts eventually landed him in prison. Shortly afterwards, scandal chased him from his position as a cardinal’s scribe. He then joined the army but by age 21, had decided to become a professional gambler – another short-lived career move. Next came violinist.

His course was finally set when he saved the life of a Venetian nobleman and won patronage in return. From then on, he roamed across Europe, seeking patron after patron, stopping in Paris, Prague and Vienna, Madrid and Moscow, all the while gambling, carousing and engaging in some eye-popping amorous exploits. He dabbled in Kabbalah, Freemasonry and astrology, and attracted the attention not only of the police but also the Inquisition. At 30 he was arrested, and sentenced without trial to five years imprisonment in a cell above the Doge’s palace. It was supposed to be inescapable but escape he did – back to France where he helped run a state lottery and became a spy.

Each time his debts and lusty scheming catch up with him, he moved on – from France to Holland, England, Belgium, Russia, Spain. A miscalculated prank involving a corpse left a man paralysed; he fought a pistol duel over an Italian actress; he dodged an assassination attempt. By the time he reached his fifties, he’d lost his famed looks and any money that had come his way. He returned to Venice and joined the Inquisition’s payroll.

It’s a breathless, harum-scarum itinerary, and that’s without factoring in his legendary seductions – over 120 in all, if we’re to take his word for it. But Casanova also found time for numerous intellectual pursuits. A product of the Enlightenment as much as he was a son of Venice, his polymath proclivities led him to pen mathematical treatises along with a science-fiction novel and a translation of The Iliad into Venetian dialect. He conversed with Voltaire, Benjamin Franklin and Catherine the Great among other celebrities of the period.

In 1885, penniless and exiled from Venice yet again (this time he’d published a biting satire of the city’s nobility), he found himself in a role almost as incongruous as his youthful dalliance with the priesthood: librarian to a Bohemian count at Castle Dux, in what is today the Czech Republic. Holed up with his fox terriers, it was a lonely, provincial existence, and in many ways a sorry coda to a sybaritic life spent flitting not only between bedchambers, but between some of the 18th Century’s most influential salons of power and cultural and intellectual clout. Yet had he not ended up there, his name would not be known today, for it was at Castle Dux that he composed his mammoth 12-volume memoir, Histoire de ma vie.

He began the project in 1789 on the advice of his doctor, as a sort of proto-Proustian cure for melancholia. As he told a friend in a letter a couple of years later, he would write for 13 hours a day, laughing out loud as he did so: “What pleasure in remembering one’s pleasures! It amuses me because I am inventing nothing.”

Unaccountably, it ends in mid-sentence, with a 49-year-old Casanova visiting Trieste. Though he shared select passages with friends and failed to burn it before his death in 1798, there is no evidence to suggest that Casanova ever intended the work to be published. Indeed, more than its explicit content, it’s the work’s length and the level of quotidian detail clotting its pages that made it unpublishable. It was eventually released in 1821, after editors had wielded their red pens. The censors had their way with his text, too, but even so the Vatican added it to their Index of Prohibited Books. And nor did its notoriety diminish. Towards the end of the 19th Century, France’s Bibliothèque Nationale kept multiple editions in a special cupboard for naughty books called L’Enfer (Hell).

Sexual revolution

Of course, this all helped keep his legend alive. Today, much as Justin Bieber has Beliebers, Casanova has Casanovists, a crowd made up largely of devoted amateur scholars whose day jobs in advertising or insurance sales might have flummoxed the man himself. Kathleen Gonzalez is a writer and high school English teacher in California, who first fell under his spell while working on a book about Venetian gondoliers. Bobbing along the Grand Canal, buildings would often be pointed out to her as ‘the house of Casanova’. Could they all be his? Venice happens to be her favourite city and so, following her passion, she set about writing a guidebook to Casanova’s Venice. In contrast with Casanova’s own reputation for playing fast and loose with facts, Casanovists are sticklers for details, she says.

And yet like so many aspects of his legend, that unreliability is gradually being dispelled by historians, who’ve pored over his memoirs and found that the bulk of his claims do indeed stand up. It’s part of a broader reappraisal overturning a myth that, as biographer Ian Kelly notes, “is an accident of publishing”. Because of Histoire de ma vie’sgirth, what got published initially was the erotica, which was first mistranslated from French into German, and then from French to German to English. “It’s actually a small part of his concern in the memoir”, Kelly says. “For almost every sexual encounter you get more details about the food than positions. He probably would be appalled by his current fame or infamy”.

It is ironic that the unexpurgated version, which was finally published in French and then English in the 1960s, is a good deal less saucy. At the same time, it established Histoire de ma vie as a document vital to social historians, and this in turn – coupled with new research that depicted the 18th Century as the original sexual revolution – paved the way for Casanova’s transformation from louche wastrel to Enlightenment innovator. Then, in 2010, the Bibliothèque Nationale purchased the original manuscript for a record $9.6 million (£6.5 million).

As if further confirmation of Casanova’s metamorphosis were needed, the life of this misunderstood libertine will be making its way onto the stage in March 2017 as a Northern Ballet production, based on Kelly’s biography. It’s especially apt given that Casanova himself was described as a dancer, and loved to dance.

What makes his magnum opus so important, says Kelly, is that gives us a new understanding of self, marking the birth of modern autobiography. And even though we need to get over ourselves and stop tittering at its steamier passages, we also shouldn’t discount them. “It shows us an inner as well as an outer person, and one key to that is of course going to be someone’s sexuality. What makes him fascinating is his flawed humanity, which does include his willingness to be very open about his romantic and sexual life, very much to his detriment. He writes quite a lot about sexual failure; he’s the only non-fiction writer I know who writes about what it is to fail a lover by having premature ejaculation, losing an erection. Dear god, it’s not the stuff of his legend! It’s immensely brave and the reality of a life as lived, which is touching in its way”.

And there you have it: in its immense commitment to detail and unfiltered record, Histoire de ma vie anticipates not only modern autobiography, but also every social media update that’s had you screaming ‘too much information’.

.png)