by Terence Roberts

The quest for Guyana’s fair treatment and Independence during its late colonial era in the 20th century was not only influenced by the roles of local politicians and Union leaders, but by the public’s daily exposure in cinemas to intelligent and critical Hollywood and continental European films hardly known today by a new loquacious generation.

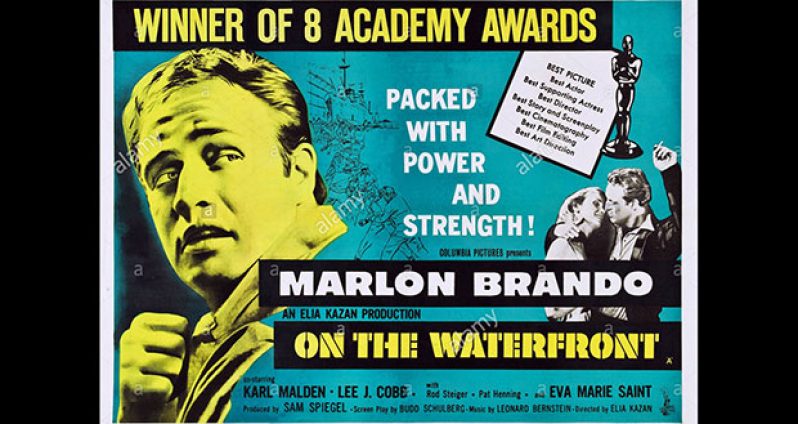

A sample of such films would include : Mutiny on the Bounty (both of 1935 and 1962); Mr. Smith Goes To Washington (1939); Juarez (1939); Kitty Foyle (1940); How Green Was My Valley (1941); Casablanca (1942); Gentleman’s Agreement (1947); Pinky (1949); On The Waterfront (1954); Giant (1956); Bhowani Junction (1956); Something Of Value (1957); Wild River (1960); The Ugly American (1963); The Seventh Dawn (1964); ‘The Servant’ (1964), etc. Even outstanding Westerns like Red River (1948), and several of the 1950s, such as Warlock; Buchanan Rides Alone; Gunman’s Walk; The Big Country; The Sheepman, among others, had coincidental relevance to social and individual conflicts related to monopolised power, inequality, racism, unrefined crudity, brutal criminal and terror gangs, also found within Guyanese society over time.

When it came to more focused social films like: All the King’s Men (1949); Viva Zapata (1952); On The Waterfront (1954); Giant (1956); or Spartacus (1960), their stories not only involved rebellion against social injustice by groups, but went further by showing how such groups, or individuals, after replacing the prior ones they criticised and succeeded, can become just the same in attitude and behavior.

ON THE WATERFRONT, one of the best films of the 1950s and American cinema, achieved deep social value by showing how the clever organized boss who rules waterfront workers for his and his friends’ personal gain, was once a poor worker like the workers himself. In GIANT, the caring, kind, poor boy James Dean, after discovering oil on his land becomes a spoilt rich egotist.

We might wonder how such American films with themes critical of colonial attitudes, social inequalities, and racial superiority, were allowed such public exposure in Guyanese cinemas during decades when colonial biases reigned? The truth is, by the 1920s the new art of cinema was such a novelty that even those administering colonial power saw their own flaws and prejudices exposed or reflected in these films, and were quite simply captivated and fascinated by them.

In Guyanese cinemas they were confronted with countless non-British films which were not concerned with upholding any prescribed colonial authority or viewpoint, but rather the individual screen-writer’s and director’s creative viewpoint. For example, the brilliant attack on the power of money and privileged authority in MAGNIFICENT OBSESSION is orchestrated by Douglas Sirk, a Danish film director who fled work in Nazi Germany in 1939 for Hollywood. Sirk’s films generally possess both a relaxed characteristic Danish and American disinterest in traditional bourgeois attitudes, coupled with a personal permissive sensuality. This was an exception to Anglo colonial reserve.

Yet such films were popular in a 20th century British colony like British Guiana. The peculiar social power and popular freedom of such cinematic culture locally is related to two facts: (1) The European influenced population of British Guiana was largely not British, but made up of diverse continental European descendants from both prior Dutch and French rule, and various new continental arrivals permitted to work under British colonial administrations since the 1830s. (2) Americans and their early anti-colonial Independence culture had been present in Guyana since the 18th century when it was still a Dutch colony; the Americans can therefore trace their involvement with Guyana back to the early 1770s, when Dutch officials and plantation owners in Demerara, Berbice, and Essequibo supported George Washington, Thomas Paine, and Alex de Toqueville ‘s Independence quest against British colonial rule in North America, and American ships from New York and Boston constantly anchored in the Demerara river, filling up on food supplies to support their Independence campaign.

By the 1930s, and especially during the 2nd World War, the British and American governments had become allies in the struggle against Nazism. British film studios and cinemas were bombed by German planes, to prevent the morale of the entire nation from feeding off the known public inspiration possible via cinematic art.

A small amount of British actors, actresses, directors, and technicians fled to Hollywood, joining other diverse foreign cinematic professionals who made Hollywood films between the 1920s and 60s the best in the world. The population of British Guiana and Independent Guyana up to the mid-1970s benefited from the daily showing of such films in over 40 cinemas located along 250 miles of coastland.

Various novices today in developing countries like Guyana may think that every new technical invention exists to replace previous ones, but experienced professionals in metropolitan countries know they have progressed because old and new processes exist together, learning from each other rather than denying or ignoring past achievements.

The tragedy of World War 2 meant that countless Hollywood films could not reach, or be shown in Europe as before, since many cinemas, cargo ships and aircraft were destroyed in enemy attacks. However, apart from Canada it was mainly English speaking British Guiana, Latin America, and the leading Caribbean islands, which came to the rescue of Hollywood’s fallen distribution and revenue.

Because BG was a larger landscape with much more cinemas than Caribbean islands, its capital Georgetown became the leading English-speaking city where the Americans transferred and circulated thousands of old and new film releases with their posters and lobby cards, which were stored in depots and booking offices around Georgetown, serving all the Hollywood film studios.

These offices and attached warehouses, the largest at the corner of Church and Thomas Streets, became a hot-house of cinematic planning and excitement, where fashionable Guyanese girls employed could be seen before their desks at typewriters with colorful dynamic classic Hollywood film posters (some of which cost a fortune today) on the walls around them. As a pleasant consequence, up to the mid-1970s Guyanese tailors and clothing designers, along with leading department stores, were kept busy making the Guyanese sexes beautifully dressed in conducive light tropical fashions which appeared in numerous films with Robert Mitchum, Robert Taylor, Victor Mature, Cary Grant, Sal Minoe, Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis jr, Alain Delon, Jean-Paul Belmondo, Ava Gardner, Nathalie Wood, Doris Day, Sophia Loren, Elizabeth Taylor, Shirley Maclaine, Jennifer Jones, Audrey Hepburn, Dorothy Dandridge and Jean Seberg.

To believe there was no beneficial effect on Guyanese society from such films between the 1920s and 70s, would be to belittle the intelligence and positive common sense of Guyanese citizens in general, and deny decades of cinema-inspired social progress. This positive attitude of citizens was certainly linked to their popular and constant consumption of Hollywood and European films of a certain era, which from the start had been a unique public art form of social criticism and optimism reflecting its creators, who were initially Europeans fleeing a Europe in turmoil and hardship spawned by Nazism and two successive World wars.

Unlike foreign metropolitan societies where the achievements of the past become known, preserved, and studied by students for future reference and influence, in a society’s like Guyana’s, the best aspects of such a past are not scrutinized and saved for the continuation of whatever beneficial social relevance it may possess. It therefore tends to become easily discarded, even denied significance in a future lacking a tradition of achievement to consult and uphold. It is therefore important to look at how such a tradition of movies remains locally relevant.