… It’s about time we invite the ‘Bholalall’ home

By Shan Razack

SO MUCH has been written about this great son of the soil on his achievements, par excellence, nay, extraordinaire, yet very little is known about Rohan Kanhai, the little country boy who nearly didn’t make it had it not been for a twist of fate. I dare say a twist of ankle! More later!

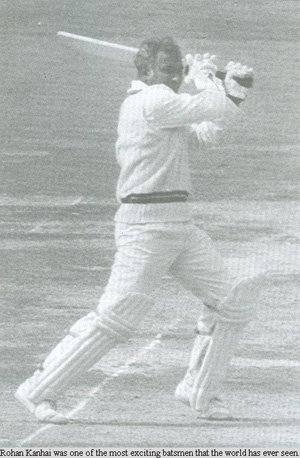

It would be difficult to imagine a more entertaining batsman than Rohan Kanhai. Quick of eye and feet, he timed the ball almost perfectly when executing a wide variety of strokes, some of which border upon the audacious and at his best he can master the most formidable bowlers with a savage yet essentially civilised assault, but he also possessed the skill, the defence, the technique and the concentration to make a five-hour Test century.

There was always some eastern flavouring in his batting, especially in his more delicate strokes, like a late cut of a surgeon performing a highly skilled operation.

The ‘Bholalall’, an All-Time Great who turns 80 was born on December 26, 1935 – a Boxing Day gift to the cricketing world – and probably that is the reason why he had been a ‘fighter’ all his life.

For the sheer pleasure that he gave the world as a batsman, averaging fractionally under 48 in a distinguished Test career that saw him rise to become the captain of West Indies, Kanhai had Bradmanesque qualities.

This implies that he was ruthless, uncaring of the reputations of bowlers, and daring in his stroke play. But at the same time he was a crafty batsman who understood the finer points of technique better than most. Kanhai was by no means a big man.

He is slightly built and stands only 5ft 7ins. He had a feline grace about him, rather like a leopard stalking its prey.

Suddenly, he would spring into action and devastate a bowler taking him completely by surprise. He scored in excess of 6 000 Test runs with 15 centuries and 28 half-centuries, and had the capacity to make batting look easy.

One of the tales you can hear about Kanhai’s batting was when he scored a sparkling hundred for Guyana against Barbados in the four-day Shell Shield tournament. Barbados had an attack comprising the menacing duo Wes Hall and Charlie Griffith, Sobers, off-spin Tony White and left-arm spinner Rawle Brancker.

It was a formidable line-up on what was a lively pitch. A great cricketer of yesteryear, Sonny ‘Sugar Boy’ Baijnauth said: “The way he hooked Hall and Griffith, maan, was spectacular. They were after him but our Rohan was just too good,”

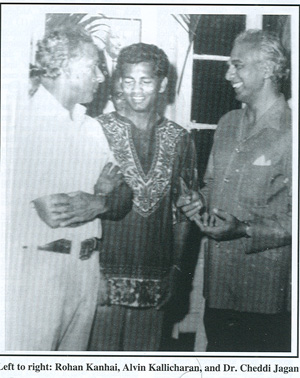

Kanhai hails from a sugar estate at Port Mourant, to which county his grandparents emigrated from India. Yes, Port Mourant, a closely knitted community and the birthplace of the late President Cheddi Jagan, reared five Test cricketers – John Trim, Rohan Kanhai, Ivan Madray, Basil Butcher and Joe Solomon in a short space of time. Interestingly enough, Kanhai and Madray both were team mates in the Port Mourant Catholic School team. Solomon, a little older had been in the team before them. Butcher was an Anglican School player, as was Alvin Kallicharran who came along many, many years later.

And still they keep coming in the form of right-arm leg-spinner Mahendra Nagamootoo.

Like most cricket inhabitants of the West Indies, Kanhai took to cricket like duck to water at an early age. At the age of eight, he was in the team at the Roman Catholic School as a wicketkeeper/batsman. In common with all schoolboys in this part of the world (Guyana), he played without gloves and pads.

He wonders why West Indian batsmen are less addicted to pad play than players of other countries. During four years, he made many runs for the school, and captained in his last season without putting together a century.

Though receiving no coaching, he advanced steadily hitting his first three figures innings for Port Mourant Cricket Club (PMCC) at sweet sixteen. Through studying the methods of leading players in 1954 he graduated into county matches, so attracting the attention of the colonial cricket authorities.

He appeared for Everest the-then East Indian Cricket Club (EICC), under the late Dr Ali Shaw – the first Guyanese who had signalled his intention of going to the Moon – in the Case Cup competition and gained a big place on the British Guiana team in 1955, when nineteen, in the match against Ian Johnson’s Australian touring team scoring 51 and 27, Thence, forward he didn’t look back.

It was late in 1954 that a feature match was due to be held at Bourda with stars like Clyde Walcott and Bruce Pairaudeau were down to turn out.

Incidentally, they were three vacancies in one of the sides and the British Guiana Cricket Board of Control (BGCBC), as it was then, asked the Berbice Cricket Board of Control (BCBC), to fill them.

Left-arm spinner Joe Ramdat, nicknamed the ‘Cobra’ was an obvious choice. The two other spots were allocated to Port Mourant and that started the right old commotion. The club reckoned that the three players: Basil Butcher, Ivan Madray and Rohan Kanhai all had equal claims. The haggling went on and on without even getting nearer to the solution until someone came up with the bright idea of drawing names out of a hat to end the commotion. You can guess who lost? Kanhai, of course!

That Thursday night the youngster was nearly in tears. To a boy of 18, disappointment like that takes on enormous proportions. It was like the end of the world for him. Remember how you felt when you broke up with your first love? But they say, fortune favours the young and the brave, or is it the young and the restless?

Next morning Mr Duncan Stuart, president of the Berbice Cricket Board of Control (BCBC), and one who had done ‘wonders’ for cricket in the Ancient County, knocked on Kanhai’s door to inform him that the ‘Cobra’ Joe Ramdat had twisted an ankle.

“Would you go to Georgetown?’ He wanted to know. “I would have walked the whole 90-mile if he had asked me to,” Kanhai said. Allow me to divert a little. In 1961, a year after youth cricket was introduced in the West Indies, right-arm leg-spinner Clement Sukdeo, was invited to the national youth trials.

Sukdeo was a prominent member on the Rose Hall Estate Youth Club and used to turn the ball ’square’ on the Rose Hall Oval.

He was an almost certainty on the national team, but for some obvious reasons he didn’t turn up at the trials. A few months later, Cricket coach Clyde Walcott (later, Sir Clyde Walcott, who created an abiding interest in the game on the sugar estates) visited Rose Hall estate to conduct coaching sessions and there he met the late Clement Sukdeo.

When asked why he didn’t attend the youth trials, Sukdeo made up some flimsy excuse that he didn’t have a proper pair of trousers. Walcott’s words to him and to the rest of us who were in the midst were, “No matter if I had to get a pair of trousers made from sugar bags I would have gone to that trials.”

Regrettably, Dr Clement Sukdeo died two days ago when his car ran off the public road at West Demerara.

I would prefer Kanhai to tell it like it was from here on. Inevitably, after the first excitement the rot set in. I began to feel nervous and couldn’t sleep.

“By the time I caught the bus with Basil Butcher and Ivan Madray at 16:00hrs on the Saturday morning my heart was pounding like a tom-tom. What a journey that was, 15 miles by bus to New Amsterdam, with the ferry then a long, hot train ride into Georgetown all the time clutching my old tattered cricket bag and trying to look outwardly calm. I hate to do this Rohan, but can I intervene a little…please! “Clutching to one’s cricket bag” seems to be the norm of the Berbice cricketers who went to play Case Cup, first-class cricket in Georgetown.

“I recall a few years ago when another outstanding son of Port Mourant, Alvin Kallicharran was in the United States he made mention of something to the effect. Kallicharran reminisced with Keith Aaron, an old friend of his from “schoolboy cricket days in Guyana”.

Kallicharran talked about his youthful days growing up in Berbice, and his excursions to play cricket in the capital city of Guyana, carrying a cricket bag that contained among other things, a fifty-cent fish and bread sandwich.

“None of us wanted to show any sign of emotion, we were, when all is said and done, experienced club cricketers playing in just another old match.

But man, beneath all the nonchalant expression we were dead scared, believe me. I had never seen a first-class match before, let alone played in one. Names like Walcott and Pairaudeau belonged to the newspapers and radio, not real everyday like on the sugar plantation.

People in England who treasure thoughts of a large yellow sun blazing down on golden shimmering sand whenever anyone mentions the West Indies should have seen the Georgetown Test ground that day. The heavens had opened in one of our not-so-frequent storms and the outfield was saturated. I remember thinking fours would be hard to hit through it, but I need not have worried.

I opened and left quickly, caught in the slips off paceman Richard Hector for a blob. At times like this, I always find it hard to do anything but kick myself. Getting out is always a personal tragedy. It cannot be anything else if you believe in the game and want to succeed. That people told me I shouldn’t worry – hadn’t Hector dismissed the great Len Hutton – they were trying to be kind but to me a failure and I’d made a real good job of mine.

Still there was a reprieve around the corner. The next morning I picked up five catches behind the stumps and surprisingly won myself a place in the British Guiana trials to be held on the same ground the following week.

My reputation as a wicketkeeper/batsman was beginning to spread and with it my flair for the unorthodox. But, unlike the majority of today’s big names I never dreamed of going on to Test glory, club and possibly colony cricket was all I wanted out of life.

A haul of 62 runs and five catches in the trial brought me a call for the second and third trials, both of which rained off in true Manchester style.

So, on the strength of that one performance, I found myself in the British Guiana party to fly to Barbados for a couple of games in February, 1955.

I was only the number two wicketkeeper to Cliff McWatt who held down the Test spot at the time but that didn’t matter a bit.

I have never been out of British Guiana in my life and here I was about to fly 500 miles with some of the world’s greatest cricketers. Unfortunately, Ivan Madray and Joe Solomon – an automatic choice for the first trial – didn’t make it. Much to my surprise, as I considered the elegant Basil Butcher, the king-pin of our club, with the other two not far behind.

I still remember the names of my 12 companions to this day: Bruce Pairaudeau (capt.), Clyde Walcott, Glendon Gibbs, Lance Gibbs, Clifford McWatt, Sonny Edun, Richard Hector, Cecil ‘Bruiser’ Thomas, Pat Legall, Norman Wight, Basil Butcher and the manager Lennie Thomas. As expected, I was the drink-waiter in the first game and was included for the second purely as a batsman at No.3. It was to be the worst experience of my career.

The Barbados team was littered with big names including Frank King, the Test quickie with a hatful of distinguished scalps to his credit. I’d never faced anything like King before. Boy, he was fast, mighty fast and banged down some of the most colossal bumpers I’ve ever seen. To a little fella like me it was like being shelled on Dunkirk beaches

I’ve never in my life collected so my bumps and bruises on my arms and legs as I did that day – all for 14 runs.

An hour afterwards I still couldn’t put one foot in-front of the other. This was my introduction to the world of pace. Like most batsmen, I’ve never particularly liked it but I’ve tried not to allow anyone to master me. The match was remembered for one thing – my first meeting with Royalty. The charming Princess Margaret, who was holidaying in the Caribbean, was in the crowd to see my effort to savage King’s thunder-bolts.

Afterwards, we all met her, but I was so scared I couldn’t offer a darn thing to say. I was pleased to rub shoulders with Royalty as I was to come through my first colony match with my reputation intact. Hobnobbing with Princess would go down well back home in Port Mourant.

“Ian Johnson’s Australians were due to begin their tour of the West Indies a couple of months later, and we quickly get down to even more trials before picking our side to meet them. The Aussies are always an attraction whenever they play. They have the killer instinct and will fight until they drop rather than admit defeat. What’s more they are a nation of gamblers, all of which helped to endear them to the West Indies public who like nothing better than a good fight. Each colony game brought a capacity crowd and Georgetown was no exception. I mentioned earlier after making the team as a batsman I shocked Keith Miller by clouting 51 runs, cross-bat and all. I must admit though that Peter Burge’s butter fingers helped a lot.

He dropped me at 22 – off a catch that he would hold 99 times, out of a hundred. I swept Ian Johnson off the meat of the bat to Burge at midwicket. It was going like a bullet but it was straight and to hand. Perhaps, unconsciously I did the wrong thing by making Burge spill the catch. He murdered us for 177 runs, the same total it had taken eleven of us to muster, and won the match for the Aussies.

“The fight for places on the English trip began in earnest in October 1956, when we held our Quadrangular cricket tournament in Georgetown. There’s no doubt about it! I’ve always been one for the big occasion and, true to tradition, I stepped up my game belting 129 against Jamaica (my first meeting with Roy Gilchrist), and followed up with another hundred off the mighty Barbados attack. I was doing very nicely, thank you, and Clyde Walcott was quick to let me know.

At lunch in the Barbados match, the mighty drawled: “Good going man! I’ll be seeing you on the boat to England. ‘As he turned away he added, ‘Get that double century and I’ll give you one of my bats’.” “With 129 already chalked up I figured that no one can stop me anyway, but I overlooked one person – me. I ran myself out for 195. To tell the truth, I felt sick all the whole darned time, but I still got my Walcott bat.

“I got among the runs 62 and 90 in the first two Test trials staged to help in the selection of the party to tour England. I never doubted my batting ability from the day I could hold a piece of wood between my two small hands, but when I finally got on the boat as a wicketkeeper/batsman, it was the greatest shock I ever experienced in my whole career,” said Kanhai.

In the first three meetings with England, he kept wicket in preference to F.C.M. Alexander in order to strengthen the batting, but since then he has seldom figured behind the stumps, preferring to concentrate upon run-getting.

Like other West Indies batsmen that year, he did not produce his best form in England, where his aggregate in five Tests amounted to 206 runs, average 22.88. In the next three summers, Kanhai played for Aberdeen in the Scottish League, in 1961 he assisted Milnow and in 1962 Blackpool, both in the Lancashire League. Between these professional engagements he appeared regularly for the West Indies. He figures in all five home Tests with Pakistan in 1958; he played five times against India and three times against Pakistan in 1958-59, hitting 256-his most cherished performance at Calcutta- and 217 at Lahore. During this tour he scored 1,518 runs, average 58.38.

In1958-59 he played in all Tests against England, staying six hours eighteen minutes for 110 in a vain effort to save the match at Port-of-Spain, Trinidad.

A year later he participated in the epic tour of Australia where in five Tests he hit 503 runs, average 50.30, scoring 117 (in just over two hours) and 115 in the drawn match at Adelaide. With the aid of 252 against Victoria (Ian Meckiff and et) he headed the West Indies batting figures for first-class matches with an aggregate of 1,043-a record for the West Indies batsman in Australia-and an average of 62.29. In the West Indies in 1962, he was chief run-getter against India with 495 runs (two centuries) at 70.71 an innings and in England he scored 497 in the five Tests.

For his success Kanhai says he owes a tremendous amount to Frank Worrell, whose advice has helped him to an incalculable degree since he set foot on the ladder of first-class cricket.

The most difficult decision of his life, he says was when he pulled a hamstring before the second Test at Melbourne 1960-61. They said that he could not play, and he spent a sleepless night bemoaning his misfortune. Next morning he approached Worrell and said that, if the captain were willing, he would turn out. Worrell decided to take the chance and Kanhai scored 84 and 27.

A knee injury troubled him for much of the tour of England and it deteriorated so much that a specialist advised him that he would be taking a calculated risk if he appeared in the final Test at The Oval. It was suggested that if he wished to put the limb to rights, then an immediate operation would be advisable. Again Kanhai decided to play and he hit 30 and a dazzling 77 in seventy minutes which helped materially in a victory for the West Indies by eight wickets.

When asked about his batting he explained, “You have to develop a sound technique, especially a tight defence. It is not that the defence should be the basis of your game, like in the case of a couple of Englishmen. A defensive stroke can get you a single if you learn to place the ball.

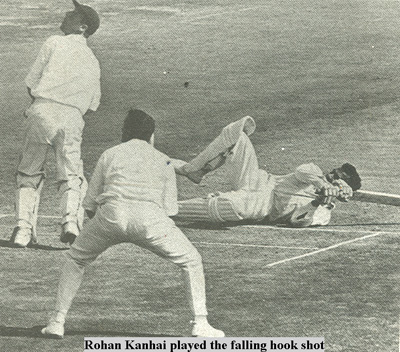

As far as stroke-making is concerned, you have to put every poor delivery away to the boundary and sometimes even hit a few good ones too. It is when you do the latter that the bowlers are made to think. The odd risk is worth taking provided the percentage is on your side. He played what is unique in the annals of the game – the falling sweep. After hitting the ball, he would fall to the earth as the ball flew out of the ground.

I suppose I played it to awaken myself, he remarked with a chuckle. There was no risk at all but I had to do something different.

It is not uncommon for batsmen who began their careers as leading stroke-makers to finish as part of the supporting cast. Age converts the carefree into the careworn. Rohan Kanhai is a good example of a batsman who began inventing strokes against the best bowling and ended by playing “experienced” innings in the shadow of the next generation. Contrast the dare devilling of his batting with his sedate and thoughtful effort in the World Cup final against Australia in 1975.

His half-century in the company of Lloyd who eventually made a punishing hundred, steadied the ship. It was an almost white-haired Rohan Kanhai who played his lone World Cup and finished on the winning side. A match-winner, the best player I ever saw. Thank you for the enjoyment and memories, Rohan!

.png)