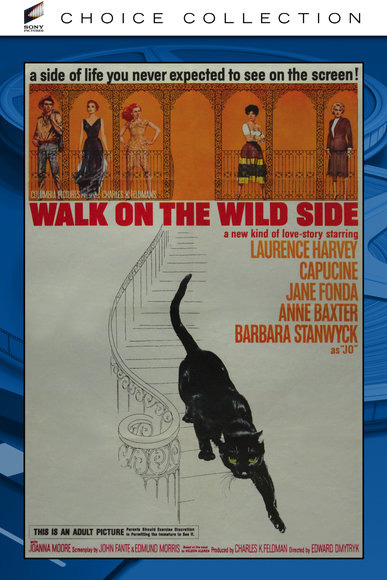

THE first hint of this film’s creative brilliance begins with the design of its poster with a black cat descending an ornate staircase, which is just a minimal vertical drawing below a horizontal balcony, upon which the film’s five lead characters stand.

Before looking at the actual quality of this film I should mention an additional and new aspect of its embedded social value, relevant far beyond any simplistic definition of ‘Walk on the Wild Side’ as a North American, ‘Hollywood’ film, strictly about North American society.

I first saw the gigantic colour poster for this film in Georgetown in late 1962, or 63, when Guyana was still called British Guiana, prior to its Independence from Britain in 1966. The film opened at the intellectually inclined Plaza cinema on Camp Street, one of the most beautiful two-laned streets for four blocks, which gave this beloved classic cinema unique visibility if you were going north or south on Camp Street’s broad one-way tree-lined streets with a pedestrian avenue in the middle.

Two huge poster boards stood at a slant above the north and south ends of Plaza’s marquee, allowing pedestrians, cyclists, and motorists to witness the gigantic posters of major films currently playing for weeks, at least.

One can imagine the presence of a poster like that described above, with dimensions at least 8 ft by 10 ft.

Additionally interesting, was the fact that Georgetown had just suffered devastating arson that would drastically reduce the traditional attractiveness of this city’s downtown, and begin an exodus of citizens who could not adjust to its comparative decline.

Yet, throughout this distressing era of racial and political conflict, a huge cosmopolitan young and elderly section of citizens remained in a hectic social mood (evidenced in various local newspaper archives), by the atmosphere of daily social pleasure generated by seriously engaging weekly film programmes which fluctuated on the big screens of at least six closely situated downtown cinemas, whose publicly seen posters, like ‘Walk on the Wild Side’, did not advertise glossy close-ups of fried chicken, soft drinks, cosmetics, etc, but a bonanza of social, intellectual, and extra-curricular cultural & educational stimulations.

FILM GRAPHICS

The film opens with the gripping close-up of a black cat walking towards us as the theme song, ‘Walk on the Wild Side’, is sung by Brook Benton against Elmer Bernstein’s dramatic score. It is probably one of Benton’s best rendered songs in his impressive list of progressive Blues numbers. The black cat meets a white cat, the song stops, and the two cats fight briefly but viciously, until they separate, and the black cat walks on, stealthily, as Benton’s song begins again. This entire central presence of the black cat as a figure in this film is a powerful semiotic reference to the animal instincts within all carnal creatures. There is no other reason for the cat to be so prominent on the film’s poster, or opening scenes; since there is no REAL cat in the rest of the film.

Dmytryk’s style substitutes realism for dramatic structural effect, which we immediately see when the hitchhiking drifter, Laurence Harvey, meets the young ‘wildcat’ country girl played by Jane Fonda, in one of her first and greatest performances ever on screen.

They meet as homeless transients who use huge cylindrical drainage pipes (sexually symbolic?) for shelter on the road to New Orleans, the low-lying tropical Southern city where most of the film takes place. Dmytryk’s style emphasizes the structural contrasts of architectural interiors against the figurative outlines of his cast, so that the small road-side diner run by a Latino woman, played touchingly by the experienced Anne Baxter, where Harvey and Fonda stop, will be meaningfully contrasted with the wealthy ornate setting of the New Orleans brothel, where we will meet Capucine as the sophisticated high-class prostitute, and Barbara Stanwyck as Jo, her shrewd, tough, but elegant Madame.

STORIES WITHIN THE STORY

The film’s story, about the apparent fatalistic end to a love affair based on the pardoning of a prostitute by her original boyfriend, cannot be taken literally at face value. Dmytryk’s style instead subtly exposes various social problems: Fonda’s American racism towards Baxter’s ethnic Latino identity and successful material independence built by honest labour, in contrast to Fonda’s air-head quest for easy living in a New Orleans bordello. Harvey’s long lost girlfriend, played by Capucine (a beautiful 1960s actress of unique films), provides the example of the talented individual who comes to the big city to pursue a career in Art, fails, and ends up in a corrupt capitulation. Harvey’s idealism and forgiveness of Capucine is commendable, but perhaps too doggedly heroic, since it provokes the authoritarian violence of Stanwyck’s and her henchmen, who need Capucine’s continued cultured, refined, high-priced sexual favours for rich clients.

DMYTRYK AGAINST STEREOTYPES

Dmytryk’s film repeatedly destroys stereotypes; as when a reunited Harvey and Capucine are identified as ‘sinners’, and abused on the streets of New Orleans by a roadside Preacher, and Harvey’s brilliant outburst defines the Preacher as far from Christian, forgiving, kind, or morally exemplary. It is not Capucine’s sale of corporeal sensual pleasure that is really criminal, but Stanwyck’s organized crime brothel holding her prisoner. Within such a mileau, Capucine in a profound scene, extracts a large sum of money from a wealthy client who dotes on her beauty and sophistication; then, never admitting her reason for the sum, she goes down to the brothel’s salon where her black jazz musician friend is performing, and with a kind word she puts the stack of money in the mouth of his trumpet. Her sympathy for the racial difficulties of the underdog is clear.

WALK & CRITICS

This film, which upset a number of ‘critics’, was once derided as ‘inept and laughable’. Harvey, of Anglo South African birth, playing a white Southerner, and Baxter, a white Hollywood actress, playing a Latino woman, who is actually the best, the most loving and socially humane character in the film, were both called ‘miscast’. Nothing of the sort. Dmytryk was after their dramatic skill, not racial realism. Brook Benton’s mellow voice soars ironically at the film’s end, singing ambiguously: “You walk on the wild side, you better walk humble, or you’re gonna stumble; one day of praying and six nights of fun, the odds against going to heaven, six to one.”

by Terence Roberts

.png)