IT is probably fair to admit that the perception of a decline in the arts has been a repeated observation since antiquity, and may become apparent by an interest in diverse examples of how art is made, and how numerous aspects of our world keep changing. For the average person there may be no awareness of a possibility of a more comparative and self-conscious effect of the arts upon ourselves; but for the idealistic artist it becomes normal to seek creative approaches to art-making which will arouse, focus, and sustain interest.

THE RESERVOIR OF WRITING

In creative writing the first structural unit of communication is the sentence; but though comprised of words, the creative sentence has no obligation to make their arrangement obey a step by step simple logic, for example, such as what I am trying to explain here, now. For this reason, the more we regard the history of creative writing as a reservoir of examples about how ‘quality’ is maintained over a ‘quantity’ of written banalities, we are led to ignore categories which divide the use of written language into ‘poetry’ and ‘prose’.

Everyone adores Shakespeare for the use of his language. However, as a playwright it is his closer relationship (than us) to the three profound classic Greek dramatists of BC, Sophocles, Aeschylus, and Euripides, that we first see a more concise use of language which no doubt influenced Shakespeare by their works imagistic, figurative, and tonal qualities. In a play by one of these dramatists a messenger brings unhappy news to a king; the king becomes angry upon hearing it and verbally assaults the messenger, who replies: “Your heartache were the doer’s, your earache mine”. This sentence is a synthesis of both a precise explanation, or understanding, and profound linguistic artistry. In another of these Greek plays a mother chastises her daughter with: “You infamous wretch!” to which the daughter replies: “Infamy is caught by contact with the infamous”.

LANGUAGE QUALITY

To regard such use of language as relevant only to the category of antique oral stage dramas, but not to prose fiction, would be to censor the freedom of creative writing on the whole. But such freedom is curtailed from the start if we regard prose fiction as nothing more than the grammatically correct unfolding of a ‘story’, minus the more particular narrative detail of an engaging tone of voice, the representation of time passing, or sight drawing in detail what it sees, or juxtaposed words and descriptions which use language to travel in and out the human mind, into the external world, via sentences, paragraphs, fragments, or chapters.

PETRONIUS’ EXAMPLE

In ‘The Satyricon’ by Petronius we read the narrator’s description of being taken care of by the poor young woman, Oenathea: “For my part, I was admiring the ingenuity bred by poverty, and a sort of artistry evident in each object: No Indian ivory set in gold shone here; no marble pavement gleamed beneath our feet, beguiling the earth-floor with its gift; instead a willow bed-frame topped with straw….cups molded by a cheap wheel’s easy turn; soft limewood drinking

bowls, and wooden plates made from the pliant Osier-tree; and jars stained by the dregs of wine. The walls around, packed with light straw and random mud applied, were lined with rustic nails, from which there hung a broom of slim reeds, tied with rushes green, that lowly cottage guarded other wealth dangling from smoke-stained beams; soft service-berries, dried Cretan thyme, and clustered raisins hung, entwined among fragrant wreaths.” Is this rural Roman scene simply obsolete antiquity, or is it still a reality somewhere today? The language of Petronius’ ‘novel’ therefore preserves timeless organic earthly reality. In this sense, art does not ‘decline’.![]()

APULEIUS’ EXAMPLE

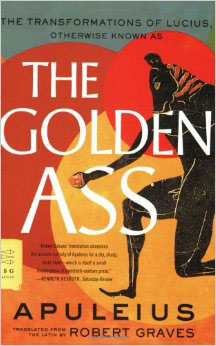

In the 2nd century AD, ‘The Transformation of Lucius’, or, ‘The Golden Ass’, by the Roman writer Lucius Apuleius, appeared, and here we see the universality of vivacious creative ‘novel’ writing, offering stories within stories, reeling cinematic imagery before cinema was dreamed of, and imaginative and magical transformations concerning a young man turned into an ass by a Goddess, then thankfully back into human form at the novel’s end, in chapter 18, which begins: “I rose at once, wide awake, bathed in a sweat of joy and fear. Astonished beyond words at this clear manifestation of her God-head, I splashed myself with seawater and carefully memorized her orders, intent on obeying them to the letter. Soon a golden sun arose to rout the dark shadows of night, and at once the streets were filled with people walking along as if in a religious triumph. Not only I, but the whole world, seemed filled with delight. The animals, the houses, even the weather itself reflected the universal joy and serenity, for a calm sunny morning had succeeded yesterday’s frost….the crash and thunder of the surf was stilled, the dark clouds were gone and the calm sky shone with its own deep blue light.”

by Terence Roberts

.jpg)