Understanding Epilepsy in Guyana

FOR many years, epilepsy in Guyana has been shrouded in misunderstanding, with those affected often facing stigma, discrimination, and even isolation. Commonly mislabeled as “fits” and attributed to supernatural causes, seizures are widely misunderstood, making life even more challenging for individuals living with the condition. However, through advocacy, education, and support initiatives, organisations like the Epilepsy Foundation of Guyana are working to change perceptions and ensure that those with epilepsy receive the care and understanding they deserve.

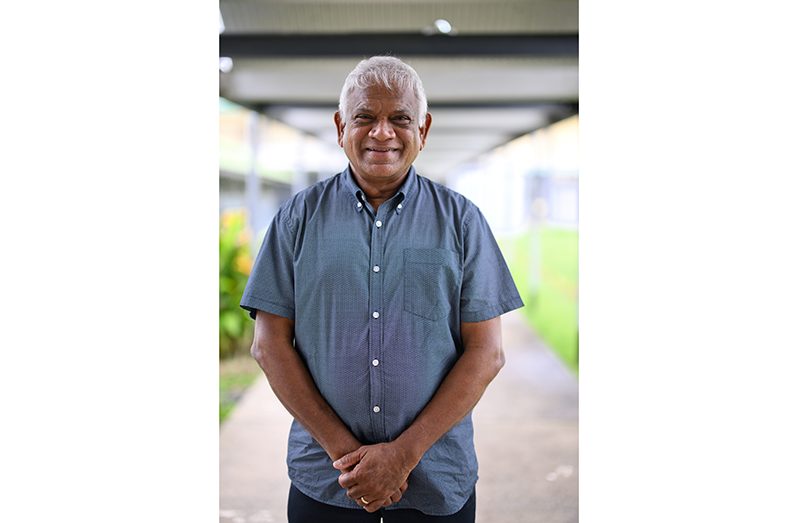

This week, The Pepperpot Magazine sat down with University Lecturer and founder of the Epilepsy Foundation of Guyana, Dr. Thomas Singh, and the foundation’s Vice President, Deidre Ifill, to better understand what it’s like living with epilepsy, the stigma people face, and how family, friends, or even strangers can help.

Living with Epilepsy

When Dr. Thomas Singh was writing what is now called his Common Entrance Examination, he had a seizure. Teachers and fellow students rushed to help him, but not many of them knew how. This, he says, encouraged him to start the Guyana Epilepsy Foundation more than 10 years ago.

Thomas was later diagnosed with epilepsy and suffered from a type of seizure called chronic tonic, which caused involuntary jerking of his body. Now, sixty-two-year-old Thomas is the founder and president of the Guyana Epilepsy Foundation. He is also one of the country’s leading economists and has lectured at the University of Guyana for the past 20 years.

Like so many epileptics in Guyana, growing up came with a unique set of challenges. Despite this, Thomas says that he was fortunate simply because his parents understood that epilepsy was a serious medical condition.

“I was very fortunate. I went to a school where most people understood, but in particular, my parents understood that the condition was a medical one,” he shared. “Very often, people who experience seizures and epilepsy might not be that fortunate. They might be living in environments where they and the people around them think that there’s demon possession or that a person is mad. I was very lucky in that regard.”

Now an educator, Thomas and his foundation are passionate about tackling the lack of understanding about epilepsy in the education system. As he explained to The Pepperpot Magazine, “Teachers can’t manage seizures. And there have been instances in Guyana where students, young people with seizures, if not epilepsy, are asked to leave school. This has happened. So, the cumulative effect could ultimately affect people’s livelihoods.”

He also noted that seizures can manifest in different ways, adding, “When I was getting my seizures, these different kinds of seizures, I mentioned absence seizures. Sometimes it could be simple twitching, touching of one’s skin. All of that could be a form of epilepsy. In my case, the stiffening and the jerking, I experienced this at any time, at any place. That’s the nature of seizures.”

One of the lesser-known seizure types is absence seizures, which can cause learning challenges. “There is a very mild form known as absence seizures, where people simply lose attention and they space out,” he said. “And this bothers us particularly in the case of children who are learning. Because any learning loss that might happen once or twice tends to accumulate over time. The cumulative effect could be that a child is unable to complete school. Another reason why children often do not complete school is because of the misunderstanding.”

One of the most interesting and little-known facts about epilepsy is that while seizures are uncontrollable, people suffering from epilepsy say they can feel when they are about to have one.

For Thomas, it felt like what he could only describe as “a tumbling in his head.” “It could be a smell, it could be a feeling. In my case, it was a feeling, and I can only describe it as a tumbling in my head. Now that I know it was triggered by brain activity, I can relate to that notion and identify it as a sort of a tumbling in my head.”

He further added, “I recall particularly riding my bicycle—I was at Camp Street—and I had a seizure. I remember when I was in the United States, I was in a cinema, and I got a seizure. I had just stepped off a train and got a seizure, and it was cold, it was snowing.”

Now, decades later, Thomas’ journey with epilepsy took a positive turn. Today he no longer has seizures, something not many people thought would be a possibility.

“At a certain point in time, I stopped getting seizures. I became an epileptic in remission, if you will, and that’s important to know as well,” he shared.

He further explained, “It is possible that after being managed and having one’s seizures controlled so that one is seizure-free for a period of time, a doctor might say—you should always have a doctor—‘Let me wean you off the medication, and let’s manage the process.’”

Myths and Misconceptions

Another voice in raising awareness is Vice President of the EFG, Deidre Ifill. Having been a part of the foundation for several years, coupled with her experience in social work, Deidre dispelled a few popular myths that people may still believe when it comes to dealing with a person having a seizure.

As she explained, “People believe that with that type of seizure, you could bite your tongue off or you could swallow your tongue. I just want to reiterate that that is not possible. Some things that you should avoid doing when a person is having a seizure, especially of that nature, include trying to put anything in the person’s mouth.”

She further added, “We as Guyanese tend to rush to the spoon. I don’t know what meaning or attachment they have to the spoon, but we have a tendency to put a spoon in the mouth of someone having a seizure. We also see salt in hands, splashing water on people—all of these are no-nos.”

Moreover, Deidre shared that most seizures last between 1 to 5 minutes, and it’s best to let that period run its course. In the rare cases that a seizure lasts for longer, we are encouraged to get medical help as soon as possible.

Although we may be tempted to perform some of the long-held Guyanese remedies when we are in the company of someone having a seizure, Deidre shares a few of the correct practices. “If a person is having a seizure, you need to ensure that people around them know they suffer from epilepsy or seizures. Letting persons know in advance what to do is a big step.”

According to Deidre, being open and speaking about epilepsy is a significant step in reducing stigma.

“The more people know about epilepsy, the better it is for those living with it and the people around them. If someone is having a seizure, the first thing to do is ensure they are lying safely on the ground. Clear away anything that might hurt them, and if possible, turn them on their side. If not, let them run the course of the seizure. Timing the seizure is crucial.”

Understanding epilepsy, dispelling myths, and ensuring proper response are essential in breaking the stigma. Through awareness, education, and advocacy, epilepsy no longer has to be a condition that isolates individuals but rather one that unites communities in support and care.