AS we celebrate the Revolution of Kofi in 1763 in 2025, we must expand our reflections to recognise that every county of the three former colonies of Guiana—Berbice, Essequibo, and Demerara—is deeply entangled in the historical narrative that shaped our nation. They all share a common debt of slavery and resistance. However, Demerara can be argued as the most significant in the rise of Guyana’s early colonial economy, emerging as a key site of economic movement, albeit one shrouded in the shadows of chattel slavery.

We cannot ignore this fact as we conclude this year’s Black History Month. To add clarity, we must reflect on the presence of the Dutch leader Laurens Storm van Gravesande, Commandeur of Essequibo and later Director-General of the colonies of Berbice and Demerara (1750–1772). Wars in Europe and shifting alliances perhaps provided the impetus to open the Dutch colony to English planters—aspiring plantation owners.

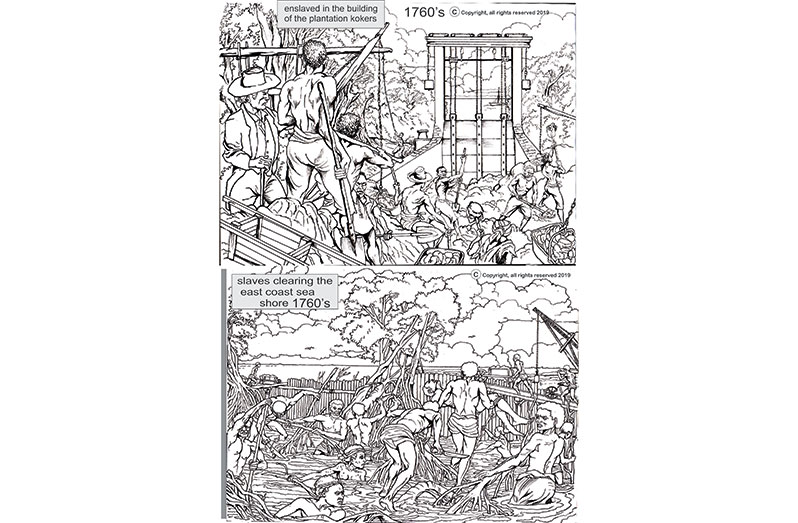

One crucial aspect of our national heritage is understanding the process by which Demerara was established as a viable plantation colony. First, this required reclaiming land from the sea. The records of the Venn Sugar Commission of 1948 estimated that each square mile of cane cultivation required the construction of forty-nine miles of drainage canals and ditches, along with sixteen miles of higher-level waterways used for transportation and irrigation. The commissioners noted that the original construction of these waterways must have involved moving at least 100 million tons of soil. This meant that enslaved people, armed only with shovels, moved 100 million tons of heavy, waterlogged clay while enduring perpetual mud and water and competing with the hazardous creatures of that habitat. The number who perished during this gruelling process was not recorded. Yet, it was through their labour that the humanisation of the Guyanese coastal environment in Demerara was achieved.

This process also involved extensive construction work on the kokers (sluice gates) and canals. While the Dutch, whose homeland was constantly threatened by the sea, perfected the science of the kokers, it was the French who commanded the construction of two canals that would border Stabroek. When the French took Stabroek from the English, Admiral the Comte de Kersaint, in 1782, initiated the proclamation that:

This process also involved extensive construction work on the kokers (sluice gates) and canals. While the Dutch, whose homeland was constantly threatened by the sea, perfected the science of the kokers, it was the French who commanded the construction of two canals that would border Stabroek. When the French took Stabroek from the English, Admiral the Comte de Kersaint, in 1782, initiated the proclamation that:

“Religion would have a temple, justice a place, war its arsenals, commerce would have its counting house, and industry its factories, where the inhabitants may enjoy the advantages of social intercourse.”

The French Admiral also ordered enslaved labourers, forcibly taken from grumbling plantation owners, to dig two canals—the North Canal, corresponding to present-day Croal Street, and the South Canal, corresponding to Hadfield Street. These canals surrounded Stabroek in 1773.

Again, we must pause in solemn reflection, acknowledging that the physical toil and hardship of our enslaved ancestors laid the foundations for the initial civilising of our native land.

Happy Mashramani to the nation!

.jpg)