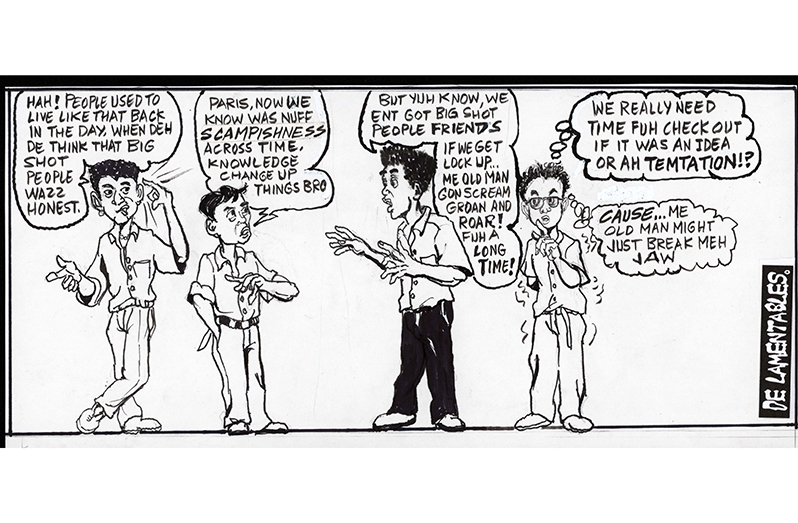

Most fathers and mothers face the predicament of dealing with the burden of so-called ‘social adjustments’ that our children encounter. Much of what I’m referring to are cultural impositions carrying creeds contrary to what we collectively know has worked for us and what we have held sacrosanct as core values. These adjustments often conflict with our preferences, challenging what we know is right in favour of what will help us fit in with the group on the corner.

An elder who knew my family well once shared a phrase with me repeatedly: “The hecklers of misguidance shout the longest and the loudest.” He would often relate this to the Biblical hecklers, paid by the priests, whose heckling ultimately led to the crucifixion of Christ. In today’s world, choices often revolve around group accommodation, which might seem beneficial for material gains but may cause the loss of treasured individuality. This individuality can be replaced without immediately recognising the vague, untrustworthy persona that emerges—an identity enveloped in the whispers of doubt, replacing once-solid character traits and interactive tattoos of proven personality.

We believe in lineage, yet it is not always accurately recorded. A father may have been a hero to family members but could fail to address the interests of his own offspring, leaving a void. In such instances, the most popular peers in the community become influential voices. What do these peers, themselves survivors of a society paying only partial attention, teach? Often, they impart survival mechanisms. These mechanisms are not always criminal but are rarely altruistic and frequently self-serving. This dynamic permeates all levels of society, making it crucial that dialogues appealing to the conscience of children begin at home.

The tough conversations many of us had were not always guided by religious figures but by survivors of life’s battles. These individuals, often friends of the family, believed that being a friend’s child entitled you to the talk. Interestingly, their advice frequently drew upon both scripture and classical literature. These were tradespeople, not academics, yet they read novels, hardcover books, and magazines. I remember buying illustrated classics from Latchman Singh on Camp Street. I passed this method of engaging with books to my children. Even in today’s age of unimaginable platforms of influence, we must navigate through the liberties they offer, many of which are disguised entrapments preying on our choices.

The tough conversations many of us had were not always guided by religious figures but by survivors of life’s battles. These individuals, often friends of the family, believed that being a friend’s child entitled you to the talk. Interestingly, their advice frequently drew upon both scripture and classical literature. These were tradespeople, not academics, yet they read novels, hardcover books, and magazines. I remember buying illustrated classics from Latchman Singh on Camp Street. I passed this method of engaging with books to my children. Even in today’s age of unimaginable platforms of influence, we must navigate through the liberties they offer, many of which are disguised entrapments preying on our choices.

One such mirage today is the overwhelming temptation of gambling. Beware: what seems like today’s needs may expand due to poor decisions. Gambling is not an investment. Many years ago, I heard a piece of wisdom from a gambler known as ‘Tum-bay’ or ‘Sparrow’ from Lodge. Sparrow said, “A gambler doesn’t win money; he only wins back part of what he lost.” I recall one Old Year’s Night on Punch Trench Road, Bar Street, watching a gambling duel between Loui and the late Acka Tiger. My attention, however, was on the beautiful sister of a Roots businessman, patiently waiting for Loui to win so they could attend the dance. It never happened—Loui lost. As the old folks say, “Sometimes, you’ve got to learn from other people’s mistakes.”

The age we live in raises more challenges, but references from the past still hold valuable lessons. Examine the road you travel. Explore every strange suggestion that promises overwhelming rewards, especially when the cost seems to be just “a little thing.” Don’t envy how quickly you think your neighbour benefits. You might learn the true story the hard way.

.jpg)