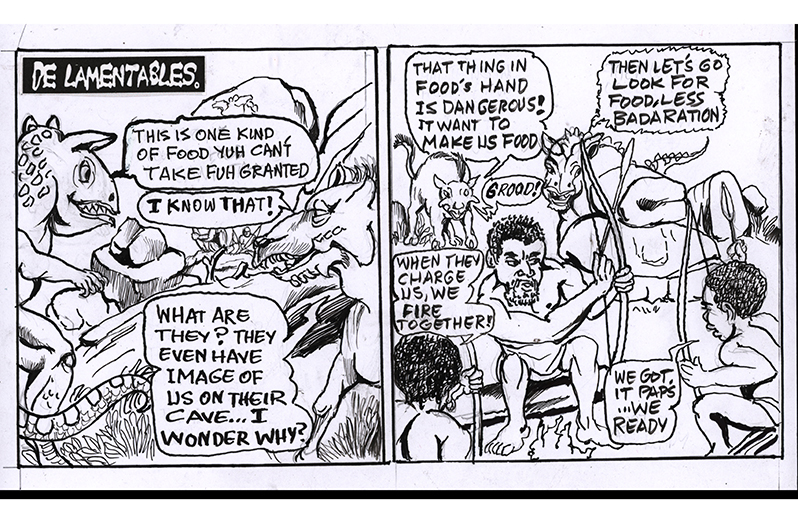

BEFORE the art of the alphabet was sculpted in stone, we discovered that the fruit we observed other species of tree climbers eating could, apart from appeasing our hunger, also colour our fingers. This enabled those among us with a strange ability to shape the creatures of our world and fears, and thus, the first artists emerged. Art became the expression that enabled our initial primitive logic and awareness, particularly due to the need to interpret the other terrible creatures of our world that would harm us and prey upon us.

With time, deeper observation was added, which led to further shaping of familiar imagery. We defined the hostile prehistoric predator not as a friend or an enemy, but rather as a challenge—a creature of awe, a test of our bravery and skill, our ability to survive, and our need to group together, forming the first tribes. With art and the mystery of the seasons, the passion to shape the world around us developed another talent: that of the inspiration of the scribe.

With time, deeper observation was added, which led to further shaping of familiar imagery. We defined the hostile prehistoric predator not as a friend or an enemy, but rather as a challenge—a creature of awe, a test of our bravery and skill, our ability to survive, and our need to group together, forming the first tribes. With art and the mystery of the seasons, the passion to shape the world around us developed another talent: that of the inspiration of the scribe.

These talents were opened to the tribe, allowing them to question, suggest additions, develop beliefs, and, above all, create laws. The capacity to draw and sculpt the world around us induced a need for storytelling and music, expanding our imagination through the first rituals. This gave purpose and interpretation to our relationship with the world and our sense of belonging, along with our first efforts to define the concept of “whose world and what borders enveloped our spheres” from a tribal perspective.

It was the creative arts that enabled the evolution of our species despite challenging climates and the defiant layout of the lands we inhabited. We had long begun to conceptualise the seasons as controlled by ‘Gods’, with priesthoods presiding at times contrary to logic. In areas with more difficult terrain, human sacrifice was offered to the Gods. For example, the rise of ancient Khemet could not have triumphed without methods like irrigation systems developed through observation of the Nile’s flow. This no doubt coincided with the levels of collective teachings and the independence that allowed the creation of minds like Imhotep.

When we look at the oldest scripts, from ancient Khemet to the Maya, there are languages written by graphic designers—hieroglyphs, stone seals from the Indus Valley, clay tablets of the Sumerians, Chinese characters, and beyond. Art was a crucial ingredient on the path to what we now term civilisation.

It is not rational to evaluate that during anticipated times of conflict, the preservation of works of art and artefacts is held in such high esteem, often to be concealed before even human casualties occur. The continuity of the tribe becomes even more evident through this. Thus, the preservation of significant landmarks and icons larger than life will remain a people’s resurrection and continuity. I’ve always wondered why some national authority did not retain photographs of past historic buildings; perhaps the answer lies in the nation’s lapse in valuing the arts through a long aesthetic slumber.

.jpg)