THE reluctant Emancipation was not an ideal blessed by the plantocracy that held power over the colony. Even the appointed Governors were subject to them; neither did it find favour with their super-rich plantation owners in London- that is not to say that the poor of London benefitted from them either. Frustrations propelled the manumitted Afro-citizens to seek their livelihoods in the capital of the colony, which their blood and sweat had cemented into being over the previous 200 years. But the owners of the Plantations also recognised that the skills of production lay with the expertise of the freed Africans. Thus they hatched conspiracies of divide and rule towards their aim.

One must note that it was the plantocracy whose scheming pushed the villagers towards providing services to then Stabroek. Some planters encouraged some villagers to plant sugar cane that the plantation would purchase, thus creating meaningful income towards the village, but also cultivated dependencies, as it was realised that the villages were unable to acquire the engineering support to develop their own sugar-producing mills. Some villages recorded having their own mills, at least in the postcards seen by this writer.

The planters, however, were bent on impoverishing the villages and retreating to the plantations to obtain cheap labour. The plantocracy used their influence to increase taxes on items imported that the free Afro-villages used — wheat flour, cornmeal codfish, beef, rice, cloth fabrics etc., to cripple the Afro-community as Brian Moore outlined in ‘Themes of African Guyanese History’. Thus, from the first tax ordinance after Emancipation until the end of the century, consumer goods that were identified as used by the Emancipated community were heavily taxed, resulting in hardships, but I should add, not without resistance.

The planters, however, were bent on impoverishing the villages and retreating to the plantations to obtain cheap labour. The plantocracy used their influence to increase taxes on items imported that the free Afro-villages used — wheat flour, cornmeal codfish, beef, rice, cloth fabrics etc., to cripple the Afro-community as Brian Moore outlined in ‘Themes of African Guyanese History’. Thus, from the first tax ordinance after Emancipation until the end of the century, consumer goods that were identified as used by the Emancipated community were heavily taxed, resulting in hardships, but I should add, not without resistance.

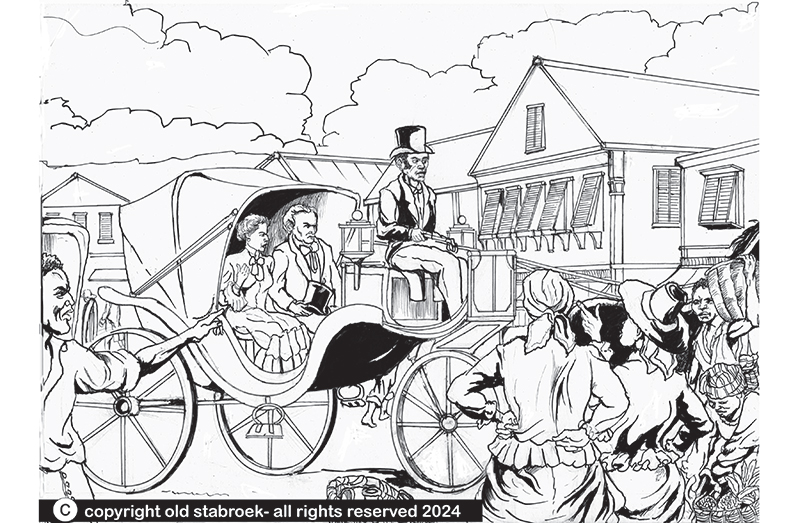

Taxation was directed at the areas of “portering, huckstering, shopkeeping, boats, cabs, mules and donkey carts”, all used by the African community business services, but those owned and used by the plantations were exempt from taxes. Successive Governors recognised that those licences discriminated against the Creoles in favour of the Portuguese, but the plantocracy’s divide and rule failed in the context of intended longevity without resistance and expected mass return to the Sugar plantations of the villagers and the wards of Stabroek. Governor Light confirmed that the temper of labourers was soured, and he admitted that remarks not of the civilised kind were made by groups of Creoles towards officials passing in carriages. The collaborative support of the merchants to the aims of the plantocracy enforced the mood of resistance that generated conflict and resulted in the Creoles’ stoning of Governor Philip Wodehouse on his way to the Stabroek wharf in July 1985.

EMANCIPATION and the intrigues of the era that followed are yet to be told, but, in closing, by the turn of the 18th century into the 19th the Afro-and Portuguese conflicts would ease into a more accommodating mood.

.jpg)