THE consistent conflict directed at the emancipated African community in British Guyana by the sugar planter community that held the colony’s authority in their hands was resisted, but while the challenges of the sugar industry increased, the African section of British subjects remained targeted.

However, in 1863, a company composed of local and English capitalists under the title ‘The British Guyana Gold Company’ sent an expedition to the Cuyuni River. Gold-bearing Quartz was discovered at Wariri on the left bank of the river, beckoning the opening of a new frontier. However, the company was abandoned due to a lack of adequate support. During the late 1870s, a crew from French Guyana also began prospecting in Cuyuni. This group is significant. They included Jules Caman, A.J. D’Amil, H.Y Ledoux, Ansdell Bernard and Vitalo. To this, a later Commissioner of Mines ‘E.G Hopkinson, credits the establishment of alluvial mining in Guyana. Jules Caman finally sold his mining interests for $30,000 Dollars, a progressive sum in the 1880s.

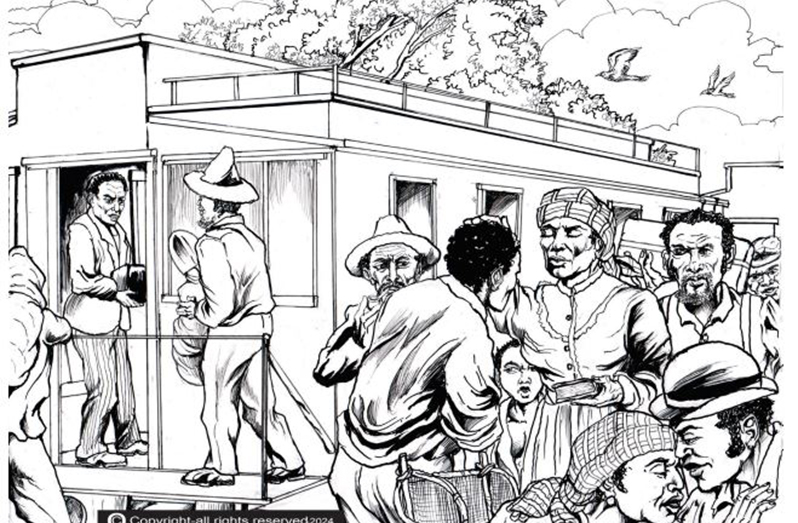

The then border dispute with Venezuela at that time had not yet come to an agreement. That would take the 1899 Arbitral Award that was finally agreed by both sides. However, in the pursuit of influencing the small prospectors, the border issue proved incapable of doing that. Thus, the government was forced to accept and recognise this rising industry by 1884. Excitement grew as new companies were formed to work the claims. They turned to the villages for labour; wages were high, but it was dangerous work, and the bell was heard in the villages. The African emancipated turned to the gold bush. They would be called the Pork Knockers in time, leaving a coastal life of scarce work on the sugar estates, and the difficulties directed at their village existence by the colony administrators.

The managers of these operations were recruited from the clerks, overseers and other people of European stock in the colony at that time, ‘Colonial bigotry persisted’. The Africans were to remain labour, working the claims while the manager, who knew nothing of mining, remained positioned on the landing. This caused them to be sarcastically called and to be eventually treated as ‘Pajama Managers.’ Mismanagement and dishonesty between the ‘Pajama Managers’ who knew little about the mining industry, also led to conflicts with the contract workers, causing many operations to close. Many companies closed, and labourers were left destitute.|

Many villagers, however, received permission from claim owners to work. They also explored old, abandoned claims. Back in the villages, work on the estate had become scarce, and sugar was not doing well. The villagers bound themselves in pursuit of a common goal in small groups led by those who knew about the bush, bought mining tools and provisions and went into the gold bush.

Thus, in the late 1890s, when the sugar estates failed the villages again, the ‘GOLD BUSH’, with its hardships, would yield El Dorado’s coveted blessings “to save the bloodline of village Life.” Their hardships and bold spirits would give rise to the mystique of ‘THE PORK KNOCKERS.’

With their lives, the Villagers paid to the bush. Culturally, they gave to the ethos of our nation, rhythms, folk songs, and a mythos of their own. Their lives are sometimes misrepresented and exaggerated, and in many cases downplayed and even slandered by people who should know better, but if explored, it would be enlightening. They did endure and kept the industry alive. We owe an incredible debt to both men and women of the Gold Bush over a century, from post-Emancipation to now.

.jpg)